Three studies on post-exertional malaise in chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) and one on ME/CFS and long COVID have recently popped up. In this blog, we cover them all.

The Distinctive Symptom – PEM (Not Fatigue)

Exercise Intolerance; i.e. post-exertional malaise – the key symptom in ME/CFS.

That “fatigue” in “chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS)” – boy, has that ever muddied the waters. Just about everyone, whether healthy or not, experiences fatigue – and regularly. The symptom is so universal that the use of it to describe ME/CFS allowed – and still allows – people to treat it like it’s nothing.

People who have it, though, know that fatigue was never it. While the fatigue in ME/CFS is simply enormous, what makes the disease so different is in the inability to exert oneself, even in a mild way, without negative consequences. Symptoms – including fatigue – worsen, and new symptoms pop up. Get into a nice strong PEM state, and things really go haywire – people retreat to dark spaces, isolate themselves, their ability to process information takes a hike, gut problems can get worse, and of course, they feel more fatigue and often more pain.

Since PEM is the distinguishing symptom of ME/CFS, we really should be able to know it, describe it, and make it distinguishable. Drug companies, after all, need to have confidence that they have an ME/CFS patient, and not some other type of patient, in their trials. If they have to use symptoms to do that, they’re going to have good measures of the distinguishing symptom in ME/CFS – PEM.

Some work has been done on that by (who else?) Lenny Jason. Lenny Jason’s DePaul Questionnaire contained a PEM subscale which contained 5 symptoms that participants rated according to how severe they were and how frequently they occurred:

- A dead, heavy feeling after exercise

- Muscle weakness even after resting

- Next day soreness after everyday activities

- Mentally tired after the slightest effort

- Physically drained after mild activity.

In 2018, Jason and company added four additional questions that addressed how long the symptoms lasted, and one which asked if the person had reduced their activity levels to avoid PEM. Jason then used the PEM subscale to see if it could differentiate people with ME/CFS from people with two other highly fatiguing diseases: multiple sclerosis and post-polio syndrome (PPS). (Note that both of these diseases could be considered post-infectious diseases.)

In, “A Brief Questionnaire to Assess Post-Exertional Malaise”, the Jason group reported that the subscale was able to correctly identify 80% of the ME/CFS, MS, and PPS patients.

In the present study, Workwell Foundation researchers took their slant at the problem. Who better to assess PEM than Workwell? They regularly, after all, employ the greatest stressor of all – exercise – in their 2-day exercise tests in research studies and for disability. A past exercise study found that assessing four symptom categories (fatigue, pain, immune, and sleep-related) accurately classified 92% of ME/CFS 164 patients and 88% of healthy controls.

That was a good step forward, but Workwell wanted more. They wanted to be able to come up with a questionnaire a doctor could very quickly use in their office to determine whether a person experiences PEM, and therefore, likely has ME/CFS.

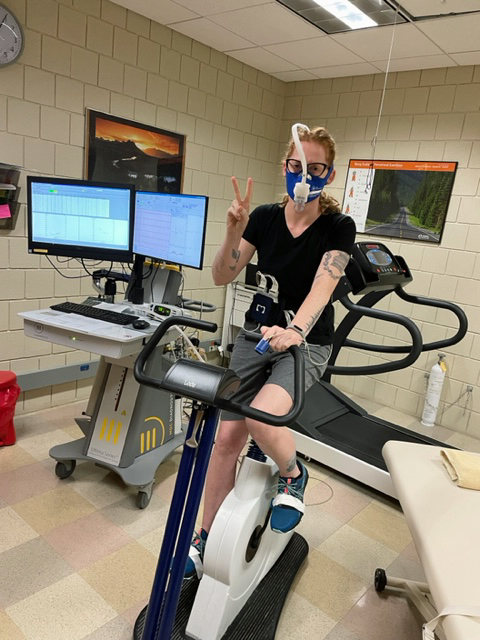

Workwell used two cardiopulmonary exercise tests to assess PEM in ME/CFS.

A Simple Diagnostic for PEM?

The study which, included 49 people with ME/CFS and 10 sedentary but healthy controls, assessed their symptoms for up to a week after the exercise.

- Cardiopulmonary symptoms

- Cognitive dysfunction

- Cold limbs

- Decrease in function

- Fatigue

- Flu-like symptoms

- Gastrointestinal disturbance

- Headache

- Increase in sensitivity

- Light-headedness

- Mood disturbance

- Muscle/joint pain

- Neurologic symptoms

- Pain

- Positive feelings mood

- Sleep disturbances

- Temperature control

- Tingling

- Weakness.

While the study was small, the results were fascinating in what they may tell us about ME/CFS and the effects of exertion.

First Exercise Test and the Next Day

Cognition was impaired in about 30% of ME/CFS patients but not in any healthy controls. Twenty-four hours later, PEM was clearly creeping in as 40% of ME/CFS patients experienced cognitive dysfunction while no healthy controls did. Fatigue was very common (@80%) in the ME/CFS patients but was much less frequent in the healthy controls (37-20%), despite their general lack of physical activity.

Muscle and joint pain was interesting, as it charted with the “burn” healthy people can experience after exercise. It was almost nil directly after exercise in the healthy controls, climbed for the next couple of days, and then disappeared completely by the end of the week. It was present in ME/CFS (38%), climbed the second day (57%), then stayed at about 40%.

Second Exercise Test and the Next Day

For the first time, a decrease in function was seen. Thirty-five percent of patients report decreased functioning 24 hours later, but no healthy controls do. Fatigue is actually heading downwards in both the healthy controls and, surprisingly enough, in the ME/CFS patients. Both groups experienced higher rates of fatigue 24 hours after the first exercise test (@ 80% for ME/CFS; 27% for HCs) than the second (63%, 9%). (I don’t know if these are statistically significant).

Twenty-four hours after the second exercise test, it appears that some adaptation has occurred, at least in some patients, as “only” 63% of ME/CFS patients report fatigue. Still, while most of the ME/CFS patients report fatigue, only 9% of the HCs now do – they are almost all over it. The same was true of weakness; over time, weakness actually declined in ME/CFS from 37% after the first test to 21% after the second test, but weakness is not present at all in the HCs 24 hours after exercise.

For the first time, sleep disturbances pop up (37% in ME/CFS vs 0% in HCs). Cognition gets whacked – not in everyone or even in most people with ME/CFS (33%) – but not at all in the healthy controls (0%).

Seven Days Later

Workwell does not measure the “second-day effect”, where some people report symptoms really ramp up, but they do assess symptoms after 7 days. Things are, in general, getting better. Fatigue continues to lower a bit – now 59% of ME/CFS patients are experiencing it, but get this – zero healthy controls are reporting experiencing fatigue. Muscle/joint pain and pain overall have remained pretty stable in the ME/CFS patients (39%, 33%) but have also completely disappeared in the healthy controls (0%).

Overall Symptom Reports

Looking at whether a symptom has been reported by a person at some point, it was clear that the symptoms in people with ME/CFS popped in and out over time as the percentage of symptoms reported at least once typically far exceeded those reported during any one of the exercise days.

Ninety-six percent of ME/CFS patients (vs 55% of HCs) reported increased fatigue by the end of the study. Muscle/joint pain showed a similar pattern (86 vs 36%), but the key findings are still to come. What Workwell wants are discriminating factors, though, and that’s what is next.

Discriminating Factors

Symptoms like reduced functioning, cognitive problems, sleep issues, lack of positive affect and headaches after exercise made the ME/CFS patients stand out.

Workwell was primarily after symptoms that could discriminate the PEM ME/CFS patients’ experience from the healthy controls; i.e. symptoms that were common in PEM but almost rarely produced by exercise in healthy but sedentary controls. Fatigue and muscle/joint pain wouldn’t do it – they occur too frequently after exercise in everyone.

Some healthy controls may still feel some fatigue or muscle pain, but they never experienced problems with functioning. Not one HC has reported a drop in functioning, yet 61% of ME/CFS patients reported they did. The pattern is similar – far more people with ME/CFS experience headaches (57 vs 9%), pain (53 vs 9%), sleep disturbance (57 vs 9%), lightheadedness (50-18%), weakness (55-18%), and far fewer experience positive feelings/positive mood. Remarkably, while only 18% of people with ME/CFS reported experiencing positive feelings at some point, 73% of healthy controls do.

The researchers were able to track how discriminating the symptoms were as the exercise test proceeded. The more the ME/CFS patients exercised, and the longer Workwell tracked symptoms, the easier it was to differentiate people with ME/CFS vs the healthy controls.

First Exercise Test

First, the researchers found experiencing any two of the following symptoms 24 hours after the first exercise test was highly discriminating (AUC – 898; Specificity – .818; Sensitivity – .878).

- Cognitive Dysfunction

- Fatigue

- Headache

- Pain

- Absence of Positive Feelings/Positive Mood.

Twenty-four hours after the 2nd exercise test, any two of this larger set of symptoms more highly discriminated ME/CFS. (AUC -.927, Specificity – 992, Sensitivity – .861)

- Cognitive Dysfunction

- Decrease in Function

- Fatigue

- Headache

- Pain

- Absence of Positive Feelings/Positive Mood • Sleep Disturbances.

Finally, symptoms found a week after the exercise stressor produced a veritable lock on an ME/CFS diagnosis. With the healthy controls fully recovered, but with many of the ME/CFS patients still suffering from PEM, presence of any one of the following symptoms produced the highest degree of certainty yet that a person with ME/CFS was present. (AUC-949, Specificity – 1.000, Sensitivity – .895). I don’t know if you can get a much better example of the long-lasting effects of PEM after exercise.

- Cognitive Dysfunction

- Decrease in Function

- Fatigue

- Muscle/Joint Pain

- Pain

- Sleep Disturbances.

Reduced Functioning and Lack of Positive Feelings After Exercise

Exercise tended to improve the healthy, sedentary controls’ moods. Not so in ME/CFS, where few reported positive feelings and almost 30% reported a mood disturbance.

Functioning, or the lack of it, is the key problem in ME/CFS. Komaroff’s stunning 1996 study found that functioning was significantly worse in ME/CFS than in serious diseases like heart failure, diabetes, and multiple sclerosis. A 2019 survey found that “reduced stamina and functional ability” was the most common consequence (99.4%!) of ME/CFS, yet the authors pointed out that functioning as a criterion has never received its due either in the research or the medical realm.

Reduced functioning only explicitly showed up in ME/CFS criteria after 2017 and sixty to 98% of medical records of ME/CFS patients fail to even mention problems with functioning. Doctors tend to underestimate the extent of a patient’s disability by two-thirds. Most clearly still don’t get it about functioning and ME/CFS.

A couple of exercise studies that have assessed how exercise affects functioning show declines in the number of steps, decreased activity, increased number of naps, and reduced cognitive abilities.

It was notable, given the well-known emotional benefits of exercise (i.e., the “runner’s high”) and its ability to increase energy levels and feelings of well-being – even in people with depression – that few people with ME/CFS experienced that. The healthy controls did – 73% of them reported feeling more positive, but only 18% of ME/CFS patients did. Meanwhile, 29% reported feeling symptoms associated with a mood disturbance while none of the healthy controls did.

A Personal Experience

One wonders what would have shown up if the survey had been extended one more day in order to get in the day two hit after exercise. I kept an eye on my symptoms after a double-espresso-powered day that required an extraordinary amount of walking (11,600 steps!) and some substantial driving. The range of symptoms I went through was remarkable.

- Day 1- I felt little pain but felt fatigued and weak, and so I rested. The most interesting symptom was that I could not take in or enjoy nature.

- Day 2 – The next day, I had lots of burning muscle pain, and felt edgy, but my mind felt sharp. I was able to enjoy nature again – it was like it suddenly clicked back into focus. Still fatigued, I walked a little and was a little fluey by the end of the day.

- Day 3 – Despite resting for two days, day 3 was in some ways my worst day. My burning muscle pain was worse, I had heart palpitations during the day, and my mental sharpness was gone, I had difficulty concentrating, some dizziness, and the fluey feeling kicked in during the afternoon again.

A Simple Diagnostic For PEM Indeed…

In the end, the authors proposed that if a doctor asked someone if they experienced increased fatigue, cognitive dysfunction, lack of positive feelings/mood, or a decrease in function after exercise, and the person answered yes to two of those symptoms, the doctor could safely assume that they have ME/CFS.

Well, you might say maybe those are just the background symptoms of ME/CFS. Maybe after a week, people with ME/CFS are back to baseline? The next Workwell study answered that question.

The Recovery from Exercise Study

Recovery was rapid in the healthy controls and most recovered within a day. It took two weeks for the average ME/CFS patient to recover.

Besides Jared and Staci Stevens from Workwell, “Recovery from Exercise in Persons with Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS)” also included Maureen Hanson, John Chia, and Susan Levine.

Involving 80 people with ME/CFS and 64 healthy but not physically active controls, this 2-day cardiopulmonary exercise test study assessed how long it took to recover from these short, but intense, bicycle exercise tests. It’s a good question. These studies are almost never done unless you are in a research study or are attempting to get disability. It’s good to know if you’re going to have to sacrifice your body either for science or to get some financial security.

This study simply followed the participants until their symptoms returned to baseline; i.e. to the same level that was present prior to the exercise tests. They used something called the Specific Symptom Questionnaire and asked for free text inputs as well.

The study showed that most of the sedentary controls not only recovered in two days but many reported they recovered in one day, and some even stated they recovered that day

Not so with the ME/CFS patients. It took them, on average, about two weeks to recover from the 2-day CPET. Around 7–8% of people had a prolonged recovery of 1–2 months, and one person, who was not included in the study because he was such an outlier, reported that he felt he had not recovered a year later. Interestingly, he had been in the low-symptom group. Workwell says their data shows them that a very small percentage of ME subjects feel that they never recover.

The answer, then, to the question, “Am I going to sacrifice my body to science (if you’re in a research study) or in order to help secure my financial future”, is no. You’re going to take a hit, but unless you’re a very rare patient, you will get back to baseline.

The authors called the “decay rate of fatigue and PEM symptoms” in ME/CFS extremely prolonged, and suggested that they responded to the exercise as if they were already “overtrained”; i.e. had already exhausted their reserves.

This helps explain why graded exercise doesn’t work – patients are asked to exercise again while they are still recovering. “Small wonder”, the authors wrote, “that graded exercise therapy has fallen into disfavor in the ME/CFS community.”

Indeed, the symptom surveys sent out before they got to the exercise facility indicated that 2/3rds of the ME/CFS participants were already considered to be in the high-symptom group. They proposed that even while at rest at home, people with ME/CFS “constantly live in the long tail of the recovery response”; i.e. they suffer from “constant and persistent PEM”.

Most interestingly, the time to recovery was not associated with symptom severity; i.e. the patients with more severe symptoms did not necessarily take longer to recover. The authors noted the concerns regarding recovery from these quite short, but intense, exercise stressors but stated their surveys suggest that most people recover within 2 weeks,

Both the post-exertional malaise (PEM) studies noted the potential applicability of their findings to long COVID – and what do you know – up popped a long-COVID/ME/CFS PEM study.

Post-exertional Malaise – A Key Symptom in ME/CFS and Long COVID?

With few exceptions, the PEM in long COVID looked just like the PEM found in ME/CFS.

The “Post-exertional malaise among people with long COVID compared to myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS)” study was a collaboration between the Bateman Horne Center (BHC) in Salt Lake City (Suzanne Vernon, Lucinda Bateman) and Derya Unutmaz’s research group at the Jackson Labs. Given that PEM is the defining characteristic of ME/CFS – the term was actually created by the ME/CFS community – it’s obviously quite important to determine how present it is in long COVID. This is the first study I know of that’s looked at this crucial aspect of long COVID in detail.

The study assessed the responses to an online questionnaire given to long-COVID and ME/CFS patients at the Bateman Horne Center. (The fact that 80 long-COVID responses (out of potentially several hundred) were received indicates that the BHC has seen many long-COVID patients.)

The Gist

- It’s the existence of post-exertional malaise – an eruption of symptoms after mild exertion – that makes ME/CFS so different from other diseases. Within the morass of other common systems (fatigue, pain, cognitive problems, sleep problems) found in it, it’s PEM that provides clarity.

- Both the most distinctive (who else talks about PEM?) and most fundamental of symptoms in ME/CFS, PEM needs to be carefully distinguished, measured, and associated with biological findings – and ultimately used in clinical trials.

- It’s the presence of PEM, after all, that hampers functionality – the key problem in ME/CFS. The devastating impact this disease has on functioning was made clear in a 1996 study that found that functionality was significantly lower in ME/CFS than in heart failure, multiple sclerosis, and diabetes.

- Most doctor reports, though, don’t even mention functionality and most doctors dramatically underestimate (by 2/3rds) how impaired their ME/CFS patients are.

- Three studies recently took a closer look at PEM in ME/CFS, and one did in long COVID. The first indicated that two short but intense physical exercise stressors (exercise tests) provoke a standard suite of symptoms across ME/CFS compared to healthy but sedentary controls.

- While it appears that some symptoms (cardiovascular, neurological, temperature issues, etc.) are not particularly provoked by exercise, all the major symptoms of ME/CFS (fatigue, reduced functioning, gut problems, sleep issues, muscle/joint pain) are.

- A distinctive enough symptom set was found that if a doctor asked someone if they experienced increased fatigue, cognitive dysfunction, lack of positive feelings/mood, or a decrease in function after exercise, and that person answered yes to two of those symptoms, the doctor could safely assume that they’re experiencing PEM – and therefore have ME/CFS.

- The recovery after exercise study indicated that ME/CFS patients, on average, took two weeks to recover. A small portion (7-8%) took up to two months to recover, and one patient reported he was not recovered after a year. Workwell, which has done hundreds of these tests, reports these “never-recover” patients are “exceptionally rare”. The healthy but sedentary controls, on the other hand, recovered within two days and many reported they’d recovered within one day.

- The authors called the “decay rate of fatigue and PEM symptoms” in ME/CFS extremely prolonged and suggested that people with ME/CFS responded to the exercise as if they were already “overtrained”; i.e. had already exhausted their energy reserves. Interestingly, people with more severe symptoms did not tend to take longer to recover.

- Finally, the incidence and symptoms associated with post-exertional malaise (PEM) in long-COVID patients appear to be nearly identical to those found in ME/CFS, with the proviso that PEM symptoms appear to be more severe in long COVID. That may be because long-COVID patients have not learned how to handle their PEM as well as people with ME/CFS.

- Documenting that PEM is a key symptom in long COVID is vitally important as PEM was little known outside the ME/CFS community prior to long COVID, and needs more study. The ubiquitousness of PEM found in long COVID should pave the way for more study of this unusual yet fundamental symptom.

The PEM the long-COVID patients experienced, however, was worse than that experienced by the ME/CFS patients. The authors suggested that this was because people with ME/CFS had learned over time how to avoid it better.

When it came to the specific symptoms the participants experienced, both groups reported that fatigue, muscle and joint pain, infection and immune reaction, neurologic and gastrointestinal symptoms, and orthostatic intolerance all worsened. The long-COVID group, though, reported significantly more sleepiness, respiratory issues, depression and anxiety, irregular body temperature, and excessive thirst.

Conclusions

Post-exertional malaise (PEM) is finally starting to get the recognition it deserves. It’s ME/CFS’s ability to inhibit functioning, after all, that makes it so particularly devastating, and post-exertional malaise – the uproar of symptoms that occurs after even mild exertion – has, thus far, only been documented in it – and now long COVID. It’s the existence of PEM that makes ME/CFS so different from other diseases. Within the morass of other common systems (fatigue, pain, cognitive problems, sleep problems) found in ME/CFS, it’s PEM that provides clarity about this disease.

Three studies recently took a closer look at PEM in ME/CFS, and one did in long COVID. They indicate that two short, but intense, physical exercise stressors (exercise tests) provoke a standard suite of symptoms across ME/CFS compared to healthy but sedentary controls.

While it appears that some symptoms (cardiovascular, neurological, temperature issues, etc.) are not particularly provoked by exercise, all the major symptoms of ME/CFS (fatigue, reduced functioning, gut problems, sleep issues, muscle/joint pain) are.

A distinctive enough symptom set was found that if a doctor asked someone if they experienced increased fatigue, cognitive dysfunction, lack of positive feelings/mood, or a decrease in function after exercise, and that person answered yes to two of those symptoms – the doctor could safely assume that they’re experiencing PEM – and therefore have ME/CFS.

The recovery after exercise study indicated that ME/CFS patients, on average, took two weeks to recover. A small portion (7-8%) took up to two months to recover and one patient reported he was not recovered after a year. Workwell, which has done hundreds of these tests, reports these “never-recover” patients are “exceptionally rare”. The healthy but sedentary controls, on the other hand, recovered within two days, and many reported they’d recovered within one day.

The authors called the “decay rate of fatigue and PEM symptoms” in ME/CFS extremely prolonged and suggested that people with ME/CFS responded to the exercise as if they were already “overtrained”; i.e. had already exhausted their energy reserves. Interestingly, people with more severe symptoms did not tend to take longer to recover.

Finally, the incidence and symptoms associated with post-exertional malaise (PEM) in long-COVID patients appear to be nearly identical to those found in ME/CFS patients, with the proviso that PEM symptoms appear to be more severe in long COVID. That may be because long-COVID patients have not learned how to handle their PEM as well as people with ME/CFS.

Documenting that PEM is a key signature in long COVID is vitally important as PEM was little known outside the ME/CFS community prior to long COVID, and it hasn’t received the study it needs. High rates of PEM in long COVID will hopefully pave the way for more recognition and study of this unusual yet fundamental symptom – and that should benefit everyone.

I would like to add that most of the doctors do not note limited functioning in their medical notes or my limitations or PEM. I’ll bring the note with list of my daily limitations (I feel very embarrassed and judged)

but they were never recorded. I think doctors should ask about daily functioning and put it in medical notes.

That’s one of the reasons for this study – to spread the word on functionality and PEM in ME/CFS. That’s one reason it’s so good that PEM is so present in long COVID. If we pass the Long COVID bill that we’re going to be advocating for, that bill will provide a lot of money to educate doctors about how to diagnose long COVID and ME/CFS. These studies are coming out at the perfect time 🙂

Hi, I agree. There is no way I would be able to participate due to severity of my symptoms. I am still glad there is this study and I am hoping they will be able to pass this bill. For me it’s a difficult “task” just to take a shower. Exercise is not something, I could do, not even in mild form. So where does it leave people like us, mostly homebound, often in bed?

I would be very pleased, if I could do that test and have only moderate PEM.

As someone who could do the test and who is often upset at the issues that I have to deal with, thanks for the reminder to appreciate what I have…:)

Cort we all think you’re wonderful and I’m sure you push yourself way beyond what you should. My recent amazed moment was when after being put through once again, ct scans, bone scans, yes there is some osteo arthritis there,xrays etc etc without any concrete result ie there’s nothing of note causing all this pain, was when I said to my doc I know it’s the ME/ CFS so he downloaded the most basic questionnaire from the internet and told me to fill it out. All it asked was where are the pain spots and if I had a certain number then yes I had ME/CFS wow, nothing about brain fog, confusion, cramps, exhaustion, disturbed sleep and so on.Truly gobsmacked, I’ve given up really, just get on as best I can and now in my 73rd year have begun to get to the stage where I refuse to do things instead of trying to please other people, including the medical industry. Unsociable, unfriendly, uncooperative? Too bad, we have to be true to ourselves. Take care everyone.

PS I can hardly sit on the toilet let alone get on an exercise bike and as for ” you need to exercise like go swimming”,I couldn’t climb into the pool let alone get out again 😀and then were seen as not trying sad but true.

Sorry meant to say that’s how he diagnosed Fibromyalgia, (have had me and fibro diagnosed 10 years ago with a different doc) he won’t talk about me/cfs just glazes over. Have tried the fibro drugs in past no help just give horrible side effects only one that gave me a little boost in mood was low dose naltrexone but no other helpful results, took it for 2 years.

Makes me wonder about those whose CFS is too severe to even DO any exercise test. Where just showering (often just once a week) or making a sandwich deplete our tiny bit of energy. How they fit into or are considered for the data and reporting of these sorts of studies. Is it even known what percentage of CFS sufferers fit into that category? My guess is their findings would be greatly different if those who were severe were included. Likely would need to have categories which would show different results depending where one fits in. Years ago when I was highly functional is a lot different than me these last 5 years.

We’ll never know because they can’t do these exercise tests. You have to be at least somewhat functional to get on the bike and ride it. The figure has been thought to be around 25% homebound. I have no idea if that’s correct.

The fact that the people who are strong enough to get on the bike – the more “moderately” impaired – still show up so differently says something about how impairing this illness can be.

I am one of the outlets of the VO2 max test. First day I was able to produce above average energy for a normal person and 2 days later, although I felt the same my energy production was below very poor. I slowly went down hill from there and took about 3 years to get back to biking, but not as much energy as before. Then I got triggered by the second Covid vaccine. Is the likely difference due to genetics or different management. Does anyone know? Thanks.

Is the likely difference due to genetics or different management. Does anyone know? – that’s the big question. How these relapse are triggered is a big mystery for me. Sometimes its clear – I just did too much. Other times – who knows?

Post viral syndromes like ME/CFS or Long Covid are very much a matter of genetics and and management. Helpful to know what your genetic predispositions are so you can consider them in your management program. (metabolic impairments can figure highly – MTHFR for example, but still not a complete answer). Nobody is looking in the right place to find good answers. Researchers have been trying to connect symptoms to treatment since the 1980s (before that really), with almost no success. even when they are looking in the right place – they – don’t understand what they are seeing. The variation between cases sometimes appears high, but the underlying causes are really very close – this becomes clear only when you understand the pathology.

And It is really not that difficult – a complete shock that no researchers have figured it out.

Hey Eric

And all the great people here. Especially, those involved in the data for the information desperately needed to solve these life robbing diseases. I, myself, had the confusing, scary acceptance of my symptons by 1994.

I would like to ask Eric if we could concentrate on any remedy first. Let’s give some sort of relief to those that suffer every minute, that would love to play with their grandkids, to see an old friend. I’d like to have one dr s appt where when ask and with tears you answer, just a short thing like, oh I’m having these mini heatstroke thingeys, I get dizzy, nautious, sweat so profusely.and totally crash out for a week. I’d like for her to say, oh that sounds miserable, I think that’s so and so. Keep notes and BP oxygen and let me know what and when it’s going to happen. Anything ,,, oh, sorry would be good.

We need relief! I’m all behind research. I appreciate every bit and Thank the serious Purpose driven angels trying to help.

Hi Shirley,

I am sure there is significant homology among ME/CFS sufferers (I would guess at least 70%). I am just going to call it CFS for ease (ME or CFS, or CFIDS are terrible labels – to me they signify that the entities using the labels do not t know what they are looking at. Far better labels would likely be small fiber neuropathy or Dysautonomia depending on symptoms and test results).

There are several known triggers for CFS – viral infection, and traumatic injury are prevalent. One of the defining criteria of CFS case is that they have suffered from it for more than 6 months. I can tell you for sure that if the problem started with a viral infection, it will have changed significantly over 6 months.

Treatment should always be based on an evaluation of history, symptoms and tests.

POTS (postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome) is a common symptom of Dysautonomia associated with CFS.

Anyone can test for this at home:

Lie down flat and relax for 5 minutes. Take your heart rate and blood pressure.

Stand up for 5 minutes without moving – keeping your legs relaxed and not moving to prevent them from acting as a pump.

Take your heart rate and blood pressure again. Your pressure cuff should be at the same level as your heart (rest your arms on a tall dresser or similar). A heart rate increase of over 30 is indicative. Your blood pressure may stay the same or increase, or may decrease as much as 20mm. A Heart rate over 120 is indicative. You blood pressure numbers are important, however few know how to interpret them. While continuing to stand and not move, take your blood pressure and heart rate every 2 minutes for the next 8 to 10 minutes.

A positive result indicates that you likely have dysautonomia (small fiber neuropathy affecting autonomic nerves).

Dysautonomia will typically have a large parasympathetic component.

One way to help your parasympathetic nervous system is with vagus nerve exercises (anyone can do them and everyone probably should). These include breathing techniques including breath holding (Wim Hof and some others are good sources), cold baths (start with immersing just your face in cold water for a couple of minutes – pull your face out of the water to breathe!), humming or singing (or gargling) stimulate your vagus nerve which passes through your throat and ears. There are good accupucture/accupressure points in your earlobes – electrical stimulation using TENS can be helpful.

Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome – Wikipedia

Cort, you say that the word “fatigue” “muddied the waters,” in describing the illness. But now–with a large audience as a result of Long-Covid sufferers–we are apt to make the same mistake with the term “Post Exertional Malaise.”

I understand that the language in a questionnaire is meant to serve a purpose, but it feels like something here is being missed. The subset on the questionnaire:

1. A dead, heavy feeling after exercise

2. Muscle weakness even after resting

3. Next day soreness after everyday activities

4. Mentally tired after the slightest effort

5. Physically drained after mild activity

My Response:

1. “Exercise?” Yeah, right. Many of us can’t even consider it. So this is a N/A question.

2. Muscle weakness is an inevitability as a result of the deconditioning that comes with having to be inactive. So people without ME think, “Of course you feel weak…you don’t do anything.”)

3. “Sore” is a word that minimizes the actual feeling, and seems to apply to anyone. A person without ME would say, “I feel sore the day after everyday activities, too.” (Because their everyday activities include moving objects, gardening, etc.)

4. While this captures severity of PEM, there are lots of people with severe PEM who don’t experience the mental crash. So if a person without PEM asked me if this applied to me, I’d say, “no.”

5. I’m not drained after mild activity. But mild activity can result in intense, immense, long-lasting pain. Additionally, “moderate” activity can cause a total wipeout.

And what is missing in all this is the quality and quantity of pain. PEM for me, like so many others, is all about a kind of pain that we never felt before. (For me, even after a 10-mile swim or a weekend hockey tournament or a bike accident.) For PEM, I use these descriptors:

1. “The pain is torturous.”

2. “It feels like I am being drawn-and-quartered.”

3. “It feels like every muscle in my body has its own stomach and they are all incredibly nauseous.”

I guess my point is that while this blog may be somewhat helpful to people without PEM, and the questionnaire is useful to the researchers, the language being used can sabotage one important point: “That PEM is a unique pain and an intense pain.” I still don’t know how we “un-muddy” the waters as regards the terminology used with this illness.

I am with you Brian! Those descriptors don’t even begin to describe PEM. The symptom list they gave the participants is much better.

What I really, really want, though, is for someone to give people with ME/CFS an exertion test – and then in minute detail assess their symptoms day by day – and then compare people. I think we would find some really interesting subsets pop out. (Love the torture analogy by the way :))

Giving people the opportunity to describe their symptoms – which Workwell did – is very helpful as well.

@Brian,

Oh, I so agree!

In fact your descriptors would be different than mine–and our descriptors seem to be different than the researchers.

For me ‘crash’ is about the energy (since I have pain whether I am crashed or not). I feel lethargic, unmotivated, listless and sometimes have trouble thinking, especially finding words. It can come on from overdoing it or even from stress (like a doctor’s appointment). I often feel it shortly after the stressor, but not always. It can last a day, two days or a week. I can have little (short) crashes and big (long) ones. And as Cort says, who knows what brings it on? Therefore, I have so much trouble with these instructions to ‘pace.’

How researchers phrase things/questions is a pet peeve I have, and not just about Covid or ME/CFS surveys. Not all people think alike or define descriptors the same. I certainly don’t. Pity all the statistical garbage that comes out of these poorly designed survey questions!

Amen , Brian

We have a defiant difference in communicable language. But “WE” understand it.

What if in research and the observance of our

Terms in communicating, knowing that some, casually reading or having the curiosity to read about these things realize most of us are not using medical terms for many reasons.

One. A dr thinks we are just faking or looking for drugs or don’t wanna work.

Two, Some of us don’t know how to use medical terminology and can’t concentrate long enough to understand it. Three Making a mistake is humiliating, that side eye, that look, that breath, we receive is hard to hear or see.

I am just wondering why we still say ME/CFS when the “CFS” part is so misleading? I remember reading in the 2003 CCC that the term ME/CFS was meant to be temporary, a kind of bridge between the two terms ME and CFS. Why haven’t we crossed that bridge yet?

The IOM committee tried with Systemic Exertion Intolerant Disease – which didn’t fly. I think the real answer, though, is that it takes a sustained effort that involves patients, doctors, researchers and federal officials to really change a name and once we got past cfs there hasn’t been much energy to do that.

Yes that is true and personally I am not a big fan of SEID either. But ME is already widely accepted in other parts of the world, and is easier to say and sounds a heck of a lot more serious than a syndrome of chronic fatigue.

It’s impossible to search online, it’s impossible to spell, it’s impossible to pronounce.

It takes a little practice to pronounce and spell, true, but it is not impossible. As for searching, fine, add CFS to your search term. But CFS on its own trivializes and misrepresents the disease condition. M.E. is way easier to write, type, and say than ME/CFS (I hate the slash). Just about everyone knows what MS is now, why not ME.

I think it’s because science hasn’t yet ferreted out exactly what causes this disease & all its symptoms. A widely accepted new name needs to be based on the actual underlying cause… which we don’t know yet.

I really like the functional assessment idea. What can’t you do on your worst two PEM days that you can do on other “new normal” days? What can’t you do on “new normal” days without provoking PEM that you could do in your previous life before ME? Of course, what I really want to know is what causes PEM and how to stop it!

I’m SO glad Lenny Jason extended his PEM study to 7 days instead of just 2. I’ve always felt much worse the 3rd and 4th days after I’ve exerted myself.

The one thing I still do not see mentioned (and I may have missed it) is that very crucial fact that if/when we ‘cross the line’ by doing too much, our baseline can move and not be restored. And, we don’t really know where that line is until it is irretrievably crossed. That lesson is always learned the HARD way.

I want to encourage all on this site to continue to be part of the education of your medical professionals. We have very recently been given better tools for their education. First and foremost, there is one and only one diagnostic code for ME/CFS. Any one previously diagnosed should make sure their records are updated with the current code. I took to my doctor a few documents which he is not able to ignore…1) current international diagnostic code with official information about its use….2) First page of a 20 page document concerning how to test, diagnose and manage ME/CFS on the Mayo Clinic site which has been guided by 20 ME/CFS experts and political action from MEAction, and the Minnesota Alliance, and 3) MEActions quick guide to testing and diagnosis, a 2 page summary.

Also, the CDC has some good pages that can be taken to a Medical Professional which is also hard for them to ignore. Call to action and summary of very specific tests they should be giving (stop taking tests that you know won’t show ME/CFS). Instead ask for the tests you actually should have.

Like Peach Blossom, I have fibromylgia. All these posts and possible excitement about clarifying PEM in ME/ CFs makes me sad if my fibro PEM is being ignored.

My fibromyalgia is much worse since my Covid infection last November.

During the infection in addition to the usual, I had excruciating painful myalgia pain in back abdomen, ribs etc so that I could hardly get out of bed and walk. While some of that got better since, if I overdo my basic maintenance PT exercises it strikes again and lasts for weeks.

Since Covid I am much more tired, confused, unmotivated, lethargic, achy and lost. Life has become decidedly more difficult and more painful. Heavy legs, breathlessness too., Do I have Chronic Fatigues/ME now too? I assume I have long Covid.

I hope some clarity is on the horizon. As for now it’s tough. In being an avid reader of your blog for years, it seems I am more alert to developments and new treatment possibilities than the doctors in my central Pa area. I am 76 now and have had diagnosed fibro since my thirties. (I first diagnosed myself from a Parade Magazine article and then found Dr Teitelman’s books) I sure am hoping for answers soon. Thx Cort for everything you do.

Thanks, Ellen…

It sure sounds like you have long COVID. There certainly is the opportunity for the RECOVER project (or someone else) to assess the effects of the coronavirus on people with FM. They could at least do electronic data searchs. I suspect though that your case is like people with ME/CFS who got COVID-19. Our little poll suggested that about 40% of people were still struggling with it 4 months later.

Of course, the opportunity now is that with the research going into long COVID something will pop and we’ll all benefit.

I just am so looking forward to PEM getting assessed in FM, Lyme Disease, POTS, etc. as well as other diseases – it may be present in RA for instance.

Thanks for this, Cort.

Speaking of Dr. Jason, and I’m sure you already saw this, but I enjoyed this recent NIH interview with him and his work in RECOVER (published March 2023): “Dr. Leonard Jason Oral History”

https://history.nih.gov/display/history/Jason%2C+Leonard+2023

I hadn’t and thanks! 🙂

Of course!

If interested, here is Dr. Bateman’s: https://history.nih.gov/display/history/Bateman%2C+Lucinda+2023

and Dr. Vernon’s:

https://history.nih.gov/display/history/Vernon%2C+Suzanne+2023

Thank you Cort for this super interesting summary!

I also think that PEM is the most informative piece for ME/CFS for research. Unfortunately, so far we do not really exploit this phenomenon enough in research. I mean all ME/CFS patients are fluctuating between better days and (mostly exercise-induced) worse days, and the difference is mostly HUGE. But rarely ever has anyone bothered to measure these differences in individual patients by doing straightforward longitudinal studies. We have tons of studies comparing patients with healthy controls but basically no descriptive data about the most central phenomenon of ME/CFS, PEM. This is deplorable because every one knows how many things are profoundly different on bad days: perfusion, CNS function, inflammation/immune function – you name it. So, by comparing lab measurements in single individuals between good and bad days we would certainly find pivotal pathophysiological differences (this is not trivial, because, plausibly, some of the compounds measured in different abundance between good and bad days must be driving PEM).

So, my hunch would be: by doing longitudinal studies in ME/CFS patients and comparing the findings between non-PEM and PEM periods we would certainly come up with candidate markers to disentangle the biopathology of ME/CFS. Now I understand that collecting samples is a challenge for this kind of study (studies couldn´t be run by appointment but rather on an ad hoc basis depending on the patient´s fluctuating health…). But maybe someone could, for example, build a network of affected health care professionals and have them draw their own blood, sample their saliva, sample their urine etc. – on both good and bad days (blood could be spun or processed by a local provider). I am sure within a couple months we´d have a “treasure of differences” – possibly containing more specific information about ME/CFS than most comparisons of patient groups with healthy controls have ever gathered.

Along the same argument. In nearly all ME/CFS studies we have some participants who are in a non-PEM state, others are in various stages of PEM. We obtain lab values from all of them, lump them together as “ME/CFS” and compare them with healthy controls. This may be a recipe for finding nothing really significant as these “ME/CFS” samples are indeed a mixture of completely different pathobiological states. This may indeed be the reasons why we often find some group differences for some markers in comparison with healty controls – but the individual values are scattered all over the place with no discriminatory value for individual patients. We should really begin to establish biobanks with clearly defined and labeled samples (I mean labeled by “non-PEM” and “PEM”, and here maybe even with duration included).

All this could make a huge difference.

I agree – these are potentially ground breaking studies. The reason I knew my ME/CFS was different from everything else were the PEM symptoms. I had had fatigue before, there were times I was not as sharp, etc. but those PEM symptoms – I had never had those before…

Jarred Younger would certainly agree. He did a fascinating small FM Good Day Bad Study and got an NIH grant for a big ME/CFS study. He’s had trouble getting post-docs to write it up! But the data is there and will come out at some point…

I completely agree Herbert. Longitudinal studies through PEM, the hallmark of ME, would surely be a profoundly informative research tool.

Very interesting. Thank you Cort. Like you, my PEM is worse on day three.

Hello.

Thank you for this interesting article.

Could you please tell me where you found the information that “most doctors dramatically underestimate (by 2/3rds) how impaired their ME/CFS patients are”? I have looked through the articles but can’t find it.Thanks!

That was cited in the paper. If you click on the link to the paper you should be able to find it.

Can you please tell me which paper? I read the three articles quoted in the article but I can’t find it.

I think the questions are too simple. You can’t diagnose ME or CFS based on these questions. I also miss orthostatic intolerance and POTS. It is clear that people report or experience their feeling of fatigue after exertion in different ways. ME is a very complex disease.

A while ago I read about some studies in microbiology that had studied PEM. Then I saw something about a firm in Germany that should make some pills which they hope will cure or treat PEM. Do you know anything about this?

I’m wondering why researchers did not ask patients diagnosed with ME/CFS or LC to describe their PEM, and THEN design a study based on some key takeaways. For example the fact that many patients experience the worst PEM symptoms 2, 3 or 4 days later. Also, a Fitbit device can document many symptoms – heart rate variability, POTS, resting heart rate, steps and sleep patterns. I have LC and feel your frustration. I was an ER nurse and also an avid athlete in perfect health. I was seen by a cardiologist that I used to work with on a regular basis and blown off – treated as “anxiety “, “of course you’re fatigued “, “you’re heart is fine”. After a stress test, which a few months ago would have been absolutely nothing, I developed severe tremors dizziness and confusion, and I could see and hear how the staff became condescending . It was infuriating. It took me weeks to recover. As many LC patients are health care professionals we’re going to be seeing some very good research being done and hopefully a cure.

I don’t think these questions can be used to reliably diagnose ME/CFS. They can probably be used to distinguish ME from deconditioning, but it sounds like the study didn’t compare ME patients with people with other illnesses.

I think back to when my daughter had severe anemia. After exercise she certainly had increased fatigue, decreased functioning, and probably depressed mood. It was a pretty frightening effect. But it was anemia, not ME. (I think she did recover overnight, though.)

I am also concerned about Workwell’s characterization of that one person in a hundred as being “extremely rare.” 1% is unusual, but not “extremely rare”!

So where does the NIH’s RECOVER exercise trial “Energize” fit in here?

https://www.healthrising.org/blog/2023/04/01/recover-long_covid-exercise-clinical-trial/

I don’t know how much my experience is representative of the average, but like you said, for me, the most severe symptoms are always the third day and beyond. In fact, about halfway into the second day after exercise, I always get this bit of hope that maybe my symptoms are improving, but towards the end of that day, and especially the next day, I feel like I’m going to die. Man I wish somebody would do 3 day a study.

I have something similar – at some point I temporarily often feel increased mental clarity and am excited about the future – and then it falls apart.

OMG, RIGHT!!! What the what? LOL

I believe I came down with ME/CFS after a bad case of “mono” (infectious mononucleosis, aka “the kissing disease”) that I caught in my teens, when I first went away to college. It took me 2 years to get back to the point where I could go back to school. I was a dance major, and at that point was either in class or asleep in my dorm room. And I *always* felt worse the 2nd day after a workout that the 1st day after. It took 2 years of physical training to get to the point where I didn’t feel whacked all the time. (And then I quit studying dance, joined a band and went on the road, but that’s a whole ‘nother story.) So I’m intimately familiar with “the 2nd day is worse than the 1st”. And yes, the brain fog is part of it, not just muscle aches & pains.

This Bateman Horne Center blood work study during/after exercise between ME/CFS / Fibromyalgia and a control group is very interesting. Great tips for pacing too.

https://youtu.be/HHYlvP4e7tU.