We continue to take a deep dive into the “Long COVID and Post Acute Sequalae of SARS CoV 2 (PASC): Pathogenesis and Treatment” first-ever international conference on long COVID. Long-COVID research was always going to be a bit messy. Take a look at the name of the conference – “Long COVID and Post-Acute Sequealae”… Aren’t long COVID and post-acute sequelae synonymous with each other? Perhaps the organizers simply wanted to make sure everyone understood what the conference was about. Perhaps post-acute sequelae sounded more scientific. Who knows?

How to define things – and the name you give to them – is one of the first issues that get to be grappled with when you essentially create a new field – post-infectious disease research – out of thin air?

By prompting the medical field’s first-ever serious engagement with post-infectious diseases, long COVID is uncovering for all to see the limitations of the medical research field. Researchers who have never worked together are being forced to work together. People who are experts in other fields are leading large research efforts (the RECOVER Initiative) in a field they know little about, with predictable results. Some groups such as the UCSF LIINC and Yale efforts are leaping to the fore.

One of the great questions facing the long-COVID field, and people with diseases such as ME/CFS, dysautonomia, and post-treatment Lyme disease syndrome (PTLDS), who have been praying that long COVID research will provide answers for them – is how robust the field is. Are researchers taking it on? Has the flood of long-COVID research we expected to appear shown up? Those are topics for another blog, but the first international conference on long COVID gives us a first cut at those questions.

While Day II of the Keystone Conference mostly focused on some now well-known themes (microclots, the blood vessels, the brain, dysautonomia, and exercise), some surprising findings showed up: a neurodegenerative protein that was found in the skin, an immune response targeting the connective tissues, and a damaged liver that could be whacking the mitochondria… Check out Day I, below.

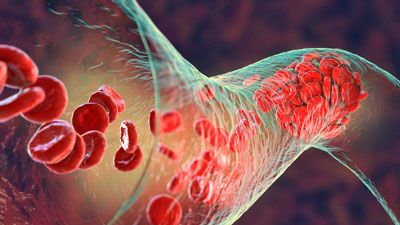

Resia Pretorious – “Microclots and Platelet Hyperactivation as Key Pathologies in Long COVID”

Dr. Pretorius has opened a new window on clotting and health, not just in ME/CFS and long COVID but other diseases as well – not an easy thing to do. From what I could tell, Dr. Pretorius mostly went over past findings with the noteworthy exception that with help from the PolyBio Foundation (if I remember correctly), her group has created an automated flow cytometry process that eliminates the subjective nature of her past analyses. That’s a big deal as that was considered a stumbling block. Her long-COVID findings have clearly spurred interest in her work, enabling this new technique to be developed – nice!

Some basics. Microclots form when inflammatory molecules in the blood cause fibrin – the substance that forms a mesh around platelets – to form a clot. Microclots are complex substances, and different types of microclots types exist in different diseases. Because they’re complex substances and differ from each other, simply quantifying them (i.e. “x” numbers of microclots are present) does not go far enough.

While Pretorius believes that microclots and platelet activation are driving a “thrombotic endotheliitis” – an inflammatory condition found in the endothelial cells lining the blood vessels – she doesn’t believe that platelets and clots are causing long COVID. The disease is more complex than that.

Still, she noted that her unusual triple therapy approach – which she believes is needed to do any good – and which includes anticoagulants and anti-platelet drugs – improved a broad swath of symptoms in 80% of long-COVID patients. Interestingly, the microclots and platelet activation disappeared in patients who got better but not in the 20% who didn’t respond to the treatment. She also noted that nattokinase helps some people.

Jane Mitchell – “COVID19 Brings Endotheliitis and Systemic Vascular Manifestations of Infection into the Spotlight”

Mitchell noted that one study found a dramatic increase in a wide variety of cardiovascular events in long COVID, including inflammatory and ischemic heart disease, and blood vessel disorders. People who had been hospitalized were much, much more likely to have these disorders.

The blood vessels in long COVID and ME/CFS are clearly being affected.

It’s clear, though, that the virus is dramatically affecting the blood vessels in long COVID, overall. One study found endothelial functioning was dramatically reduced even in young, healthy adults 3 weeks after coming down with COVID-19.

Interestingly, it does not appear that the virus is infecting the endothelial cells lining the blood vessels; i.e. these blood vessel problems are simply the result of the inflammatory milieu produced by the virus. She believes that inflammation – as Pretorius noted in her talk – is the key factor.

Dr. Mitchell is currently studying the effects of long COVID and, good for her! – the flu – on endothelial functioning. One great question for other post-infectious conditions is whether the interest in post-infectious COVID will spur studies into the effects of other pathogens. Are studies examining the effects of infectious mononucleosis – an easy target given its ability to trigger ME/CFS and multiple sclerosis – underway? While the NIH is funding some good Epstein-Barr virus research, the NIH is funding only one post-infectious mononucleosis study – by, not surprisingly, an ME/CFS researcher.

Avindra Nath, NINDS, National Institutes of Health, USA – “Neuroinflammatory Syndromes and Microvascular Disease with COVID-19″

Avindra Nath – who is currently engaged in a neurological study of long COVID – did not produce any new results either, but his presentation was so interesting that its highlights are presented.

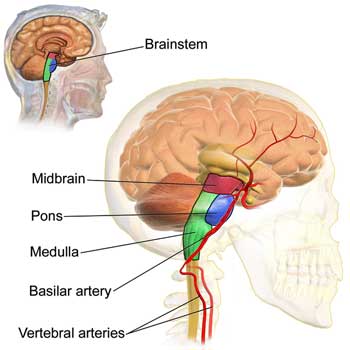

While his was an autopsy study, the potential overlap with long COVID was fascinating. Most of the people in the study were young, healthy adults with no comorbid diseases who suddenly and unexpectedly died. Most died in their sleep, probably when their respiratory centers – found in the brainstem – shut down. Nath focuses in his long-COVID talk on two areas of great interest in ME/CFS as well – the brainstem and the blood vessels.

The breathing finding was interesting given the breathing problems that many people with ME/CFS experience and the evidence of altered breathing that’s been found. Dane Cook’s huge CDC exercise study found that people with ME/CFS had trouble both getting oxygen into their tissues and removing carbon dioxide from their blood. Cook believes that people with ME/CFS are breathing differently in an attempt to load the air sacs in their lungs with more oxygen.

Nath’s study suggests that the breathing centers in the brainstem were in play. Both, of course, could be right.

The brainstem – which controls the autonomic nervous system and filters out stimuli – showed up twice on the second day.

Nath has noted before that we all carry viruses in us, and the fact that one might be present doesn’t mean it’s affecting us negatively. He pointed out that while levels of the coronavirus are very high early in the infection, after a month the number of virions detected is very, very low. Long COVID is not like herpes encephalitis where you find enormous amounts of virus in the brain. Indeed, Nath and others have been unable to find any evidence of the coronavirus in the brain, yet Nath found plenty of evidence that the brain had been severely affected.

Nath’s autopsy results found three different kinds of blood vessel damage – each of which affected different sections of the blood vessels. There were clots, thickening of the blood vessel walls, and blood vessel leakage. While blood vessel damage was found throughout the brain, the most “prominent pathology” was in the brainstem.

When his group looked more closely, they found immune factors from the complement cascade, and antibodies clustering around the blood vessels. A later examination of the cerebral spinal fluid in long COVID found a dramatic increase in IgM antibody-secreting B-cells but very low IgG-secreting cells.

IgM is the first antibody produced during an infection and it usually disappears after the infection is fought off. IgG antibodies, on the other hand, usually appear within a couple of weeks. They are like sentries sent out to look for a repeat attack and persist for long periods in the body. Why they had not been produced in large numbers was puzzling.

Like others, Nath did not find evidence of the virus in the endothelial cells lining the blood vessels. He did make it clear, though, that the blood-brain barrier is likely damaged. Looking at the substantia nigra – a part of the basal ganglia – and another area of interest in ME/CFS – Nath found evidence of massive clotting and fibrinogen leakage into the tissues.

Switching to immune cells, he found a “profound” infiltration of macrophages. A further analysis indicated that high macrophage levels were highly correlated with fibrinogen leakage; i.e. macrophages were causing a lot of destruction. Macrophages are primary mediators of the innate immune inflammatory response – and should not be found in the brain. Nath called them “unwelcome guests”. What they did not find were many T-cells; another indication that despite all the damage, the virus never made it to the brain.

To end up, he asked whether similar microvascular pathology and neuroinflammation is present in long COVID.

Jean Massimo Nunes, Stellenbosch University, South Africa – “Short Talk: Long COVID and ME/CFS: Shared Dysregulation of Coagulation, Complement Machinery, and the Endothelium Revealed by DIA LC-MS/MS Analysis of Plasma”

Jean Massimo Nunes really had his ME/CFS down. Asserting that “the precedent for long COVID is ME/CFS”, Nunes started off by referring to the late 1990s’ and early 2000s’ studies suggesting that hypercoagulation was present in ME/CFS. That promising hypothesis was subsequently squashed by a small 2006 study, which actually cautioned about placing too much faith in its results given its size (n=33) and the “heterogeneous nature of the disease.”

It clearly doesn’t take much to squash things in ME/CFS because hypercoagulation completely disappeared as an issue in ME/CFS until long COVID showed up and now is showing up in spades.

Massimo’s 2022 study, “The Occurrence of Hyperactivated Platelets and Fibrinaloid Microclots in Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS)”, found as much as a tenfold increase in microclots compared to healthy controls (who had not been infected with COVID-19). The high significance level (p<0.0001 – the result had something like a 1 in 1000 probability of being due to chance) indicated it was a solid result.

Getting back to that heterogeneity, about 50% of ME/CFS patients had microclots and platelet activation and 50% did not. Next, Nunes hearkened back to Berg’s 1999 ME/CFS study and his finding of “small amyloid fibrin” deposits.

Nunes’s untargeted proteomics search – which simply searched everywhere – found altered levels of proteins associated with, guess what – coagulation. In fact, three of the 8 most significant proteins associated with ME/CFS were involved in coagulation and platelet activation.

Nunes also found an “alarming” downregulation of complement proteins – particularly C9 – suggesting an immune deficiency was present. There was also a huge increase (7fold) in an anti-inflammatory compound called lactoferrin. Nunes noted that 2 other recent studies have found evidence of hypercoagulation in ME/CFS and no less than seven in the past three years have found evidence of endothelial dysfunction.

The new news here was that the results of Nunes’s initial ME/CFS coagulation study were validated using automated flow cytometry. Hypercoagulation is definitely back in the mix in ME/CFS.

Kailin Yin, Gladstone Institutes, USA – “Short Talk: Long COVID Manifests with T Cell Dysregulation, Inflammation, and an Uncoordinated Adaptive Immune Response to SARS-CoV-2″

Then it was onto another LIINC lon- COVID study and another repeat. Yin simply quickly ran through the results of a study published early this year and covered by Health Rising.

Yin’s study found a bunch of T-cell abnormalities, but its most striking finding was a massive disconnect between the humoral (B-cell) and cellular immune (T-cell) response in the long-COVID patients. These two systems should work together to take care of the virus: the B-cells attach themselves to viral particles to block the virus from entering the cell while the T-cells kill cells that get infected. That happened in the recovered COVID patients but not in the long-COVID patients.

Lavanya Visvabharathy, Northwestern University, USA – “Mild SARS-CoV-2 Infection Promotes Autoantibody Production in Long COVID Patients Despite Vaccination”

Oddly enough, the first short talk of the day also produced the first new results of the day. Visvabharathy reported the results from an outpatient NeuroCOVID clinic that’s seen 2,100 long COVID patients, only 10% of whom had been hospitalized. This busy group has produced six long COVID studies over the past couple of years.

Sixty percent of the cohort (called the NeuroPasc group) complained of muscle pain/ arthritis-like symptoms; i.e. they appear to be a fibromyalgia-like group – a group that hasn’t received much attention in long COVID.

An immune response associated with connective tissue disorders was elevated in long COVID.

Recognizing that many of the symptoms overlapped with common autoimmune diseases, they asked whether autoimmunity – particularly rheumatic autoimmunity – which primarily affects the joints, muscles, and skeletal system, such as rheumatoid arthritis, lupus, polymyalgia rheumatica, scleroderma, and others, was present.

In their first cut, they looked to see if a T-cell response to a common rheumatic antigen (immune trigger) called YKL-40 was present. YKL-40 elevations are associated with connective tissue problems, and lo and behold, a highly elevated T-cell response to this protein was found. The association of an inflammatory response to a known connective tissue dysregulator in long-COVID patients with muscle pain was intriguing, to say the least.

Next, they looked at autoimmunity more broadly. While she found elevated autoantibodies in both the NeuroPasc patients and the recovered COVID-19 patients, the NeuroPasc patients demonstrated striking elevations in autoantibodies associated with inflammatory myopathies (muscle damage) and lupus. Some of the autoantibodies were highly correlated with symptoms.

Finally, she wondered if long COVID was associated with increased aging.

Mitchell Miglis, Stanford University, Stanford Center for Dysautonomia – “Dysautonomia and POTS”

How new is dysautonomia to researchers at large? The person leading this session didn’t know how to pronounce the term. That seemed to throw Miglis – who is being funded by Dysautonomia International – off a bit and he immediately said that long COVID was bringing people from different backgrounds together. Not surprisingly, he spent much of his presentation explaining what dysautonomia and postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS) were.

Miglis showed that in a two thousand-plus study, about 2/3rds of long-COVID patients had a Compass score indicating they had moderate to severe autonomic dysfunction. Interestingly the autonomic symptoms often start off mild but get worse over time. Pain and sympathetic nervous system activation is common. When he dug deeper, he uncovered the interesting fact that many people with long COVID had evidence of “very mild” pre-existing autonomic problems.

In the section on causes, Miglis got the hypovolemia, mast cell activation, sympathetic nervous system activation, autoantibodies, small fiber neuropathy, and connective tissue laxity all right but then blamed the low stroke volume found in long COVID on “deconditioning” thus ignoring any other factor (low preload, early entry into anaerobic threshold) and opening a nice can of worms.

He went through the autoimmune hypothesis and the RAS paradox – which is found in ME/CFS as well – and explained that while deconditioning in present, patients do not “always” get better with exercise (really?) but that they can get worse, and then stated, “it doesn’t really make sense (for deconditioning) to explain the entirety of the pathology”. (The fact that Miglis felt compelled to assert that deconditioning doesn’t “explain the entirety” of long COVID was a little scary.)

But then it was onto deconditioning part II where Miglis himself proposed that women are more prone to long COVID because they have less muscle mass and smaller hearts and thus are affected more by deconditioning. (Miglis might want to check out Systrom’s invasive CPET studies in ME/CFS which indicated that deconditioning is not a major factor; in fact, Systrom stated that his findings were opposite to those found in deconditioning.)

Miglis did put forward the helpful idea that sex hormones need to be studied more and noted that baroreflex impairment can be found as well. He’s clearly up on the literature and predicted that cerebral blood flows (yah!) are going to be important to measure, as well as hypocapnia (low carbon dioxide levels), and mentioned ME/CFS 🙂 but then again stated that with regard to hyperventilation, “some of it is due to anxiety and some of it isn’t”.

Miglis may be raising the heart rates and blood pressure of some people with ME/CFS and long COVID with his unwillingness to slam the door on psychological issues and deconditioning, but he’s also engaged in a study that’s examining cerebral blood flows (transcranial doppler), near-infrared spectroscopy (oxygen extraction in the brain), skin biopsy, CO2, breathing regulation, tilt tests, autoantibodies….all good stuff.

Alpha-synuclein protein (dark spot) is associated with neurodegenerative diseases such as Lewy body dementia. What was it doing in long COVID? (Image from Marvin 101 – Wikimedia Commons)

Miglis surely opened some eyes when he found the pathological form of α-synuclein in the skin of a number of his long-COVID patients. Alpha-synuclein aggregates form difficult-to-break-down fibrils or amyloids in diseases characterized by Lewy bodies, such as Parkinson’s disease, dementia with Lewy bodies, and multiple system atrophy. These clumps of fibrils can impair mitochondrial functioning, increase oxidative stress, etc., and have spurred interest in a possible long COVID-Parkinson’s connection. Amyloidic particles – particles that are not folded properly and are difficult to get rid of – have shown up several times in ME/CFS studies including the “amyloid microclots” that Pretorius has found. The recent endoplasmic reticulum finding (WASF3) in ME/CFS is really intriguing in this instance because the ER is in charge of folding proteins correctly.

(On the scary neurodegenerative disease front, another study found that a coronavirus infection alters the expression of genes in the brain associated with the development of Alzheimer’s Disease. To my mind, this news is all good. If a post-infectious illness can turn a healthy, functioning individual into a bedridden, barely functional human being, it’s going to have some severe impacts. My guess is that these connections are going to continue to pop up, and as they do, conditions like ME/CFS and long COVID will be better studied, understood, and believed.)

The audience was clearly at sea regarding dysautonomia. One person – trying to get a grip on the small field – asked about the 3 most important breakthroughs of the past twenty years, and what the principal barrier to moving the field forward was. The questioner noted that his patients cringe about going to doctors who don’t know what to do.

This would have been a nice place to insert the NASA Lean Test into the discussion (but it wasn’t to be). Miglis didn’t answer the breakthrough question but pointed to physician bias, the reversion to psychosomatic explanations, and low funding, and noted that ME/CFS is in the same position. He said that physicians who are world experts in his field (dysautonomia) still say it’s all psychosomatic. (World experts in dysautonomia experts are saying it’s all psychosomatic?).

Miglis was certainly correct about the difficulty dysautonomia has had breaking into the long-COVID field. Dysautonomia was acknowledged very early on to play a role in long COVID, yet three years later, only a handful of studies have been done, and Lauren Stiles of Dysautonomia International took the RECOVER Initiative to task for not bringing in more experts in dysautonomia.

When Miglis was asked if anyone had assessed cerebral spinal fluid pressure in long COVID, he said no – and hoped they would be – and missed an opportunity to inform the questioner that high rates of cerebral spinal fluid pressure have been found in ME/CFS. When someone asked about targeting heart rate using a wearable, Miglis said someone could make a lot of money creating an app that could assess upright activity – but apparently is not aware of the STAT wearable that is attempting to do just that.

Miglis also missed the opportunity to inform his audience (a sentence would have done it) of the remarkable overlap between long COVID and ME/CFS (hypovolemia, mast cell activation, sympathetic nervous system activation, autoantibodies, small fiber neuropathy, high cerebral spinal fluid pressure, connective tissue laxity, low stroke volume).

All in all, it was a mixed bag from an ME/CFS perspective. Miglis provided a lot of good information to a clearly uninformed audience and is clearly doing good work in the field, but whether intentionally or not, he kept opening the door to issues such as deconditioning that, while present, don’t play a fundamental role in the illness and can only sidetrack the research.

The Bizarre RECOVER Children Long COVID Study. John C. Wood, University of Southern California, USA – “Brain Fog in Children”

Wood has a nice RECOVER study going, but why is the apparently cash-strapped RECOVER Initiative devoting more resources to children than to adults?

Wood noted that COVID-19 is much more likely to send adults to the hospital than children. When children end up in the hospital, only about 20% have neurologic problems – most of which are transient. Some children do, though, experience life-threatening complications. (He said that vaccinations and earlier recognition of MISC is sending that number down )

Studies that examine the cognitive effects of COVID-19 in children come up with much the same findings as in ME/CFS and long-COVID adults: slowed processing speed, impaired short-term memory, and problems with concentration and attention. Changes in executive functioning have been found in adults but not so much in children. Because “the acute injury is much less in children”, that didn’t surprise Wood at all. He even said that “clinically, this cohort is doing very well.”

So… if children, particularly pre-teen children, are less at risk and ride out the coronavirus infection much better than adults, and as several presenters noted, middle-aged people are most at risk of long COVID, that begs the question why the RECOVER Initiative has chosen to follow 50% more children (19,300) than (non-pregnant) adults (12,580) and devote so much of its precious funding to a group that seems less likely to come down with long COVID?

Those numbers were set very early in the game, and astonishingly, haven’t budged since then. How an apparently cash-strapped RECOVER Initiative decided to focus the majority of its resources on children has never been addressed. The overlap between ME/CFS and long COVID was very clear by the time RECOVER got its funding. One might have thought that someone in RECOVER would have said – gee, if children are much less likely to come down with long COVID’s cousin, ME/CFS, should we really spend the bulk of our resources following children?

One wonders if the emergence of multisystem inflammatory syndrome MIS-C, a very rare but dangerous condition associated with COVID-19 in children, changed things. Did RECOVER, in other words, neglect the fuzzier problems of fatigue, PEM, cognition, etc. in its zeal to focus on a clearly biological condition? Who knows, but RECOVER’s decision to devote many more resources to children than to adults seems uninformed and bizarre.

In any case, Wood’s hypothesis regarding the brain fog in children jived nicely with past presentations. Noting that the symptom presentation was similar to the cognitive problems found in chemotherapy (post-cancer fatigue) and traumatic brain injury (missing, once again, the disease that actually coined the term brain fog – ME/CFS), Woods noted that the common injury in all these diseases is microvascular injury; i.e. damage to the small blood vessels.

Indeed, researchers seem to be agreeing more and more that a cytokine storm produces coagulation, which then harms the blood vessels, damages the blood-brain barrier, and causes neuroinflammation.

Still ignoring ME/CFS, Wood noted that any viral or bacterial illness or systemic inflammatory illness will cause the blood-brain barrier to open up to allow the immune system to surveil the brain. In fact, mouse data shows that even a mild coronavirus infection can trigger an immune activation that opens up the blood-brain barrier. That apparently makes sense during an acute infection – the big question is why this process doesn’t shut down over time.

Data from the UK Biobank, which has brain imaging shots from before and after COVID-19, indicated that the limbic system – home of the fear response – and the brainstem, among other regions of the brain, are affected. It was no wonder, given those findings, Woods said, that problems in the HPA and HPT axes are showing up. There are all parts of the old brain that “pull levers on the cardiovascular and endocrine systems”.

Wood then covered some fantastic outside studies funded by RECOVER. (RECOVER funded 40 outside studies; the rest are all internal.) These studies should be well underway, and we have much to look forward to with them. Wood’s study is focusing on brain oxygenation, the small blood vessels, the brain-blood barrier, extracellular vesicles, etc. He’s looking very closely at how the blood-brain barrier might have been breached.

ME/CFS has never had a study that’s examined the roots of brain fog as comprehensively as Wood is doing. Once again, despite the considerable overlap between the cognitive findings in long COVID and ME/CFS no mention of ME/CFS was made.

Clifford J. Rosen, Maine Medical Center, USA – “Metabolic Aspects of PASC: The Impact of HDL and Lipid Peroxides”

An editor for the New England Journal of Medicine, Rosen stated that he wasn’t seeing many good long-COVID papers (ouch!) and actually made a pitch for people at the conference to submit their papers to him.

The metabolism has, of course, become of huge interest in ME/CFS over the past five years. Noting that glycolysis – a much faster process than mitochondrial-produced energy – is the major source of energy in the immune system during an infection, Rosen concentrated on the liver.

Rosen noted that liver dysfunction during infection can release enormous levels of fatty acids and lipids causing something called hyperlipedemia and insulin resistance producing lots of reactive oxygen species (ROS- oxidative stress) – potentially knocking out the mitochondria. That, in turn, causes glucose uptake in the muscles to go down and type II diabetes.

One researcher believes that dyslipidemia – high levels of fats in the blood – caused by liver dysfunction could be impairing mitochondrial functioning and increasing oxidative stress. (Image from Tlecoatl Zanaya – Wikimedia Commons)

The big takeaway, though, is that the system’s ability to handle oxidative stress is impaired. Rosen believes that while Type II diabetes does show up in long COVID, the really major factor is dyslipidemia. Leptin signaling shows up large. (Jarred Younger has tagged leptin in past ME/CFS/FM studies).

Lipids are a major energy source, but oxidized lipids damage the mitochondria and increase reactive oxygen species. Indeed, his lab’s work showed “markedly reduced” ATP production in T-cells.

Precision Life study found that more severe long-COVID patients had genetic issues with lipid transport and the fatigue-dominant group had multiple mitochondrial issues. Rosen’s findings were particularly interesting given Efthymios’s AI-informed recovery story which focused on liver issues.

Matthew S. Durstenfeld, University of California San Francisco, USA – “Short Talk: Cardiopulmonary Exercise Testing and Head-up Tilt Table Testing in Cardiopulmonary PASC”

In another LIINC cohort UCSF study – (UCSF and Yale showed up big time in this conference), it was great to see a cardiopulmonary exercise testing study – this time 18 months after infection. The study found a “profound decrease” in exercise capacity – a “really clinically significant difference”. Durstenfeld’s systematic review of CPET long-COVID studies found similar results. (Note to Miglis – deconditioning was not a major factor.)

Interestingly, chronotropic incompetence – the inability to raise the heart rate to the levels demanded by exercise – was the most common finding. If the heart rate can’t rise properly, not enough blood will make it to the muscles, brain, etc. Even patients with normal peak oxygen production demonstrated chronotropic incompetence.

As Durstenfeld pointed out, though, we don’t know if the heart rate is being held back because of some sort of autonomic dysfunction, or if a metabolic problem in the muscle is keeping the heart rate down; i.e. if the mitochondria can’t utilize the oxygen given to them, a signal won’t be sent to the heart asking it to increase.

THE GIST

- The second day of the Keystone International Conference on Long COVID was interesting indeed but it was rather alarming not to see any new data until the 6th talk. The fact that an editor of the New England Journal of Medicine actually made a plea for researchers to submit long COVID studies suggested that the field is struggling.

- Inflammation – no surprise – is turning out to be a key factor and appears to be driving the formation of microclots, platelet activation, and blood vessel damage not just in the body but in the brain as well. Avindra Nath put a pin on the possible blood vessel damage when he uncovered three different kinds of it in his autopsy results.

- The brainstem and other older parts of the brain such as the limbic system which regulate the two big stress axes in the body – the autonomic nervous system and HPA axis – showed up prominently.

- The viral persistence hypothesis seemed to take a bit of a hit with findings that the virus is not infecting two prominent areas associated with long COVID: the brain or the blood vessels. Indeed, Nath pointed out that viral loads drop precipitously over time and are very, very low a month after infection.

- Over 20 years since Berg championed it in ME/CFS, hypercoagulation is clearly a real thing in both long COVID and ME/CFS and is showing up not just in clotting studies but in a proteomic study as well.

- A rare look at a muscle pain long COVID cohort found evidence of an autoimmune response similar to that seen in rheumatic autoimmune diseases and striking elevations in autoantibodies associated with inflammatory myopathies (muscle damage) and lupus.

- A real surprise was finding a pathological form of protein called α-synuclein that’s been associated with Parkinson’s Disease in the skin of long COVID patients. Aggregates of these proteins produce difficult-to-break-down amyloid fibrils that can impair all sorts of cellular functioning.

- Children particularly pre-teen children are less at risk and ride out the coronavirus infection much better than adults yet for reasons that have never been explained that I know of, the cash-strapped RECOVER Initiative is following about 50% more children than adults over time.

- The common injury in all these diseases may be microvascular injury; i.e. damage to the small blood vessels. The idea is that damage to the small blood vessels and a leaky blood-brain barrier may be producing neuroinflammation.

- Liver dysfunction caused by the infection can release enormous levels of fatty acids and lipids causing something called hyperlipidemia which can knock out the mitochondria.

- A “profound decrease” and a “really clinically significant difference” in exercise capacity was found in long COVID Chronotropic incompetence – the inability to raise the heart rate to the levels demanded by exercise – was a major factor.

- Despite the remarkable overlap between long COVID and ME/CFS findings that was apparent throughout day 2, ME/CFS was almost never mentioned. (Many of the same findings show up in fibromyalgia and it is NEVER mentioned). Most long COVID researchers act as if post-infectious diseases are a new entity and long COVID is a field unto itself. In other words, they’re strengthening the very silo’s that they acknowledge are making it difficult for them to understand long COVID.

- The first part of Day 3, though, focuses on other post-infectious diseases.

Durstenfeld also failed to note the similar CPET findings in ME/CFS and long COVID. The first part of day three, though, will be devoted to other post-infectious illnesses.

Conclusion

The second day of the Keystone International Conference on Long COVID was interesting indeed, but it was rather alarming not to see any new data until the 6th talk. The fact that an editor of the New England Journal of Medicine actually made a plea for researchers to submit long-COVID studies suggested that the field is struggling.

Inflammation – no surprise – is turning out to be a key factor and appears to be driving the formation of microclots, platelet activation, and blood vessel damage – not just in the body, but in the brain as well. Avindra Nath put a pin on the possible blood vessel damage when he uncovered three different kinds of it in his autopsy results.

The brainstem and other older parts of the brain, such as the limbic system, which regulate the two big stress axes in the body – the autonomic nervous system and HPA axis – showed up prominently.

The viral persistence hypothesis seemed to take a bit of a hit with findings that the virus is not infecting two prominent areas associated with long COVID: the brain or the blood vessels. Indeed, Nath pointed out that viral loads drop precipitously over time, and are very, very low a month after infection.

Over 20 years since Berg championed it in ME/CFS, hypercoagulation is clearly a real thing in both long COVID and ME/CFS, and is showing up not just in clotting studies but in a proteomic study as well.

A rare look at a muscle pain long-COVID cohort found evidence of an autoimmune response similar to that seen in rheumatic autoimmune diseases and striking elevations in autoantibodies associated with inflammatory myopathies (muscle damage) and lupus.

A real surprise was finding a pathological form of protein called α-synuclein that’s been associated with Parkinson’s Disease and Lewy body dementia in long-COVID patients. Aggregates of these proteins produce difficult-to-break-down amyloid fibrils that can impair all sorts of cellular functioning. It’s not clear why they are showing up in long COVID, but evidence of amyloidic particles have been found several times in ME/CFS.

Children, particularly pre-teen children, are less at risk and ride out the coronavirus infection much better than adults, yet for reasons that have never been explained that I know of, the cash-strapped RECOVER Initiative is following about 50% more children than adults over time.

The common injury in all these diseases may be microvascular injury; i.e. damage to the small blood vessels. The hypothesis regarding children, brain fog, and long COVID was refreshingly similar to that seen in adults; by damaging the small blood vessels and opening the blood-brain barrier, the infection was producing neuroinflammation, which was producing the brain fog.

Liver dysfunction caused by the infection can release enormous levels of fatty acids and lipids, causing something called hyperlipidemia which potentially knocks out the mitochondria. Lipids are a major energy source, but the dyslipidemia found may be both damaging the mitochondria and increasing reactive oxygen species.

A “profound decrease” and a “really clinically significant difference” in exercise capacity was found in long COVID. Chronotropic incompetence – the inability to raise the heart rate to the levels demanded by exercise – was a major factor.

Despite the remarkable overlap between long COVID and ME/CFS findings that was apparent throughout day 2, ME/CFS was almost never mentioned. (Many of the same findings show up in fibromyalgia and it is NEVER mentioned). Ironically, given their situation – a new field, the need to learn from allied fields, and the need to grow the field which might be helped by allying it with other fields – most long-COVID researchers act as if post-infectious diseases are a new entity and long COVID is a field unto itself. In other words, they’re strengthening the very silos that they readily acknowledge are making it difficult for them to understand long COVID.

The first part of Day 3, though, focuses on other post-infectious diseases.

Has there ever been anyone more ahead of their time in the ME/CFS field than Jay Goldstein, with his limbic hypothesis?

Ha! There’s no escaping Dr. Goldstein is there?

Thanks for this Cort!

Quick sidebar – did you see the recently published Mayo Clinic Proceedings review of ME/CFS (October 2023)?

It was authored by 3 MDs from Mayo Clinic and Jaime Seltzer from #MEAction.

https://www.mayoclinicproceedings.org/article/S0025-6196(23)00402-0/fulltext

You may have already seen, but sharing if not. It has to be pretty heartening to see Mayo Clinic become, from the outside, a positive agent for change in this ME/CFS field, right?

Especially for those that have been in this ME advocacy area for a long time, I’m sure seeing Mayo affiliated with moving ME clinical care & knowledge forward has to be a welcome sight.

Are there plans for HealthRising to cover any of Mayo Clinic’s newfound resurgence into ME/CFS?

[Also quickly sharing from Jaime Seltzer, one of the co-authors from #MEAction]

https://twitter.com/exceedherg…/status/1711197702564856010

Per Jaime, “It’s in the top <1% most shared of all Mayo Clinic publications. It’s the most shared paper amongst its contemporaries at Mayo Clinic Proceedings. It’s in the top 0.2% most shared research products of all time. It’s been live less than a week."

No I hadn’t- great to hear – thanks.

I do hope the experts mentioned in this review are reading it and will take action on your suggestions. Thanks much for your continued dedication to the MECFS patient community.

Thanks! All we need is a sentence or two acknowledging that similar findings are present in ME/CFS – good for the field, good for long COVID and good for ME/CFS 🙂

Excellent recap. Thank you.

Thanks for the detailed reporting! I’m wondering whether you will be able to discuss some of the results presented by the group of Jeroen den Dunnen, who has been looking at autoantibodies in Long-Covid (and ME/CFS) as well as a mouse model of autoimmunity for these diseases?

I searched jeroen den dunnen but only could find long covid. do you maybe have a link for his research on ME/cfs? thanks!!!

His research is currently still unpublished, but has been presented at various conferences, for example this conference. That’s why I’m wondering whether Cort could give us some more insights on which specific autoantibodies etc are being looked at.

His research first centered around autoantibodies in Long-Covid and a mouse-model of autoimmunity in Long-Covid based on these, and he is now working on doing the same in ME/CFS https://projecten.zonmw.nl/nl/project/autonome-autoimmuniteit-als-een-oorzaak-van-mecvs-symptomen.

Thanks, Karl for the early heads up on this very interesting research 🙂

Hi Cort, maybe for other research on ME/cfs..But can you remember, where there not allready mouse models for ME/cfs? Long time ago? Like way back from Alan and Kathy Light or so? I can not remember anymore (brainissues) but thought there was 1 or so…

The only one I know of is the one Simmaron is working on. They are actually working on mouse models for PEM, POTS and brainfog 🙂

https://www.simmaronresearch.com/blog/do-you-want-to-learn-more-about-mouse-models?fbclid=IwAR0ANissRZA6WoEgMIzjbyk5VLuJ81jF38zhmvlXwsxz0-ui8jwG2hcpX1Y

thank you!!! the faster the better 🙂 And in the Netherlands mousemodel and at simaron… the more mousemodels there are the better..

all different… hope it moves all soon…

thank you!!!

will the mousemodel really take until 2027? do you know why it takes so long? And as i unstesand it, then they will in 2027 begin to do mousetrials. And then only farmaceuticals will jump in. and all there trials in different phases. It feels so endlesly long. And i am running out of time like so many others.sorry for question but verry severe and have brainissues. Or are they doing inbetween (prior to 2027) things with mousemodel that would earlyer help?

From what I know the work on Long-Covid will be published in the upcoming weeks, whilst the work for ME/CFS should then be something of an attempt at replication and then a possible extension. More will be known in the upcoming weeks.

Generally speaking research always takes very long, years and decades. Even once you’ve done the research the data analysis takes long, writing everything down clean takes long etc. Research is a lengthy process.

Hello Cort,

Is there an antidote to micro-clotting?

And, if there is, what effect does that have on chronic fatigue?

No formal trials have been done that I know of but Pretorius has reported that triple anti-coagulant/anti-platelet therapy can be quite helpful with a wide array of symptoms. From what I gather it’s a pretty heavy-duty or perhaps unusual protocol that it might be hard to get a doctor to sign off on, though. Pretorius also noted that over-the-counter nattokinase can be helpful and anticoagulants have been used as well. Like with everything sometimes they help and sometimes they don’t.

https://www.healthrising.org/blog/2023/04/04/coagulation-long-covid-chronic-fatigue-fibromyalgia/

Many of us are sensitive to soy so cannot use Nattokinase. I am on Ginkgo biloba and ‘baby aspirin’ which make me feel a lot better (but I don’t know how the microclots are going)

Thanks Cort for this great overview.

Hey Cort, have you considered adding a text to speech set up on your blog posts?

I’ve been reading most of your blog posts right as they come out for years now but back when i started it would take too much energy to read the whole thing, and still does, so i would only read The Gist, but since i got a text to speech app i started listening to the whole article just about every time and walk away a lot more informed

A lot of sites have a button one can click to read out the article in text to speech or they have a recording of someone reading it

It could make your posts more accessible

In any case I don’t know anything about website management or coding and I’m sure there are other factors that come into play in such a decision so I don’t know if it’s practical but I figure it would be something worth giving thought to if you haven’t already

Hadn’t thought about that. I will check it out – thanks!

What makes text to speech so useful for those with CFS is that one can be lying down the whole time audio is playing, say, if they have a laptop by their bed like i do or if they have a speaker setup, connected to their desktop pc, wired to near their bed. wireless headsets are also an option

With the apps I’ve used they always have a keyboard shortcut to jump back 10 seconds at a time or a paragraph at a time. This is very useful if one gets distracted or brain fog gets in the way of understanding for a moment and a reread is needed. I wonder if something like this could be implemented with a text to speech button, though, it might also need to be explained to the user so they know it’s there, say instructions for using keyboard shortcuts to go forward/back/pause/play. Maybe the instructions could be copy and pasted every time alongside the button if this rewind feature is deemed to be a feature that can be included

Most of the time when I see one of those reading buttons they have the number of minutes long the article is next to it so the listener won’t be scared off when they see how far down the page goes, most of the page’s length being the comments section, and think it’s an hour long article or something too long for them like that

Hope this works out for you but if not, no worries, you’re already doin God’s work out there

Best of luck to ya

The alpha-synuclein disorders of which Parkinson’s is the most common also include Pure Autonomic Failure and Lewy Body Dementia. These just refer to the main areas of the brain affected by a-synuclein, but are not discreet, separate diseases. The misfolded form of a-synuclein spreads, first gumming up the nuclei of nerve cells, slowing down their ability to transmit, and then it kills these nuclei. That is my understanding. I have had ME/CFS for going in three decades, am in my mid-70’s, and have tested positive for these Lewy Bodies—i.e., abnormal a-synuclein in my nerve cells. I doubt very much I am alone. Probably very few of us have had the skin tests for a-synuclein, but I think that those with long-standing or particularly difficult cognitive and memory trouble along with dysautonomia might want to get this checked out.

Misfolded proteins have been on kind of the fringes in ME/CFS for awhile but they are showing up more and more. Efthymios predicted that the unfolded protein response in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) was taking and hit and we just had the WASF3 finding targeting the ER.

Interesting stuff!

Do you know the specific autoantibodies associated with inflammatory myopathies (muscle damage) that you mentioned? Is this a widely available test?

U.S. Science Agencies on track to hit 25-year funding low:

https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-023-03135-x

“Despite last year’s CHIPS and Science Act, which was meant to boost innovation, report predicts that Congress will cut spending on science.”

Thanks, Cort, great work as always 🙂 About LC vs. PASC…..I’ve seen this happen before in other emerging disease classifications. They *might* (or might not) actually be different things, as different researchers working separately had been tracking different things, so I like that they’re being conservative enough to keep them kind of distinct for now.

PASC (post-acute sequelae) are all the things that can persist for three to nine months after the infection – and that would include things like shortness of breath due to lung scarring, muscle weakness and soreness due to deconditioning – i.e., longer-term results of sickness that are often slow to heal but might still be getting better at time of measurement. The folks who approached disease on this front may have been in that group who were agnostic about long-term systemic issues, and/or reluctant to jump to conclusions about chronic disease.

LC (long) is more or less by definition an acknowledgement of chronic disease. Folks studying this have set a window of 6 months, 12 months, 2 years. People studying this from an immunology standpoint, along with the folks behind public health modelling that anticipated post-SARSCOV2 emergence of ME/CFS (projected before LC studies started to be around 14%, I wish they had been right) already had a theory of disease that would fit in this bucket.

Basically it just goes to show that we don’t even have a reasonable agreed-upon model of what it is we’re studying.

I don’t know if that’s at all useful but I thought I’d point it out, just in case.

Thank you! 🙂

Whew….it’s a workout just reading all this. I imagine it was a tremendous work on your part to put this blog together! Thank you !!!

It was! Thanks 🙂