“One takeaway is It’s a disease that comes from the brain” Nancy Klimas

Avindra Nath called the project the most complex he’s ever led.

It was one of the most expensive ME/CFS studies ever done. The brainchild of former NIH Director Francis Collins, the unusual study was designed to give the NIH solid footing to move forward in a controversial disease.

The study was not designed to determine the cause of ME/CFS. Instead, the $8 million study, with its achingly rigorous patient selection process, was designed to look at a very wide array of factors and come up with solid avenues for future research.

That prospect seemed in doubt when the NIH shut down the study during the pandemic and never reopened it, leaving it about 50% shy of its initial target of 80 participants.

Avindra Nath, the leader of the effort which ended up involving over 75 researchers, said it was easily the most complex project he’d ever led. Nancy Klimas said it was “As thorough an evaluation as has ever been delivered in any clinical study that I know of in any disease”

The stakes were high. A null study finding might very well have tanked interest in the disease at the NIH. On the other hand, a positive study finding would boost ME/CFS’s lowly position at the biggest medical research funder on the planet – the NIH.

Prestigious Journal

The small study size led to concerns – that ended up being overblown – about the ability of the paper to get published in a prestigious journal. The “Deep phenotyping of post-infectious myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome” study was published in Nature Communications – a multidisciplinary journal with a high impact factor that emanates from the prestigious Nature Publications group. One review reported that the “journal’s rigorous peer-review process and high editorial standards have contributed to its strong reputation among scientists”.

The publication of the study in this journal means it will go out to a “vast audience of researchers, scientists, and scholars from various disciplines across the globe”. In other words, everybody is going to read it.

Indeed, media outlets from the New York Times, “Study of Patients With a Chronic Fatigue Condition May Offer Clues to Long Covid“, to Science, “Sweeping chronic fatigue study brings clues but not clarity to mysterious syndrome“, to Stat News, “NIH study of ME/CFS points to immune dysfunction and brain abnormalities at core of long-dismissed disease“, to Medical Express, “Study offers new clues into the causes of post-infectious chronic fatigue syndrome“, to the Scientific American, “People with Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome May Have an “Exhausted” Immune System, to the Guardian, “Scientists find link between brain imbalance and chronic fatigue syndrome“, covered it.

The Group

With almost a quarter of the group recovering, and no evidence of increased rates of orthostatic intolerance, small fiber neuropathy, sleep problems, or cognitive impairment the ME/CFS group seemed a bit different.

One thing to keep in mind is that this was a select, and in some ways odd – in ways the researchers could not have known – group of patients. The patients had to have come down with the disease after being triggered by an infection within the last five years.

In its search for rigor, the study excluded 190 of the 217 patients who underwent a detailed case review by a group of ME/CFS experts. Four people who went through the first weeklong hospital stay were excluded because they were found to have something else (cancer, atypical myositis, primary biliary cholangitis, Parkinsonism).

The patients had to be well enough to make it to the Baltimore facility and tolerate 2 week-plus studies which included at least one exhausting exercise session; i.e. they were better off than most. Several common findings in ME/CFS that have been well validated (small fiber neuropathy, orthostatic intolerance/POTS, sleep problems, cognitive impairment) were not increased in the ME/CFS group.

The strangest outcome, though, was that almost a quarter of the group (4/17) ME/CFS patients “spontaneously recovered” after the study – indicating that a substantial subset of patients may have, in some crucial way, been different from you or me.

Not Psychological – Check!

The authors stated that the participants underwent substantial neuropsychological testing which indicated “that their symptoms were reliable and a true representation of their disease”, and concluded that “psychiatric disorders were not a major feature in this cohort and did not account for the severity of their symptoms.”

Autonomic Nervous System Dysfunction – Check!

Increased sympathetic nervous system/ reduced parasympathetic nervous system activity during the day (HRV) and at night (night-time heart rate) driven, the authors thought, by central nervous system problems.

Effort Preference (Effort Preference?)

A test I’ve never seen used before in ME/CFS, the “Effort-Expenditure for Rewards Task (EEfRT)” took a rather prominent place in the paper. This test consists of a series of repeated trials in which the participants choose between performing a “hard task” or an “easy task” in order to earn varying amounts of monetary reward.

A low EEfRT means that a person tends to choose the easy task over the hard task more often, regardless of the reward or probability. This could indicate a lack of motivation, a high sensitivity to effort, or a low sensitivity to reward.

Since ME/CFS is, by definition, effortful, one would expect people with ME/CFS to have low EEfRT scores, and indeed they did. Their decline in button pressing speed over time suggested to the authors that the PI-ME/CFS participants were pacing themselves to limit exertion and associated feelings of discomfort”; i.e., they were exertion challenged. One wonders if the patients could have simply been tapped (no pun intended) out. A fibromyalgia finger-tapping study found that FM patients faded quickly as well.

Resting State – Fine

No differences in “ventilatory function, muscle oxygenation, mechanical efficiency, resting energy expenditure, basal mitochondrial function of immune cells, muscle fiber composition, or body composition” suggested that a low resting energy state was not present.

Note, though, the emphasis on the “resting state”. The condition of the ‘resting state” has never been the key concern in ME/CFS. The major issue is exertion and post-exertional malaise and that’s why physical or mental exertion stressors have been so helpful in unlocking what we know about ME/CFS.

The Hand Grip Test

Who would have thought that a simple hand grip test would have resulted in the major finding in this study?

While a low resting energy state did not appear to be responsible for ME/CFS, the authors reported that “substantial differences were noted in PI-ME/CFS participants during physical tasks“. This is almost the very definition of ME/CFS – a disease that displays more physiological abnormalities during times of exertion than during rest. That’s why so many researchers use physical/cognitive stressors in their studies.

That physical task was as simple as a maximum grip test. These tests are designed to estimate the muscle strength generated by the muscles of the hand and forearm. The people with ME/CFS were able to generate normal grip strengths.

See how the responses diverge in the Dimitrov index of fatigue resistance in [b], in the TMS test in [c], and the bold brain scan in [e], as the ME/CFS patients failed to maintain a strong hand grip over time. ME/CFS patients – red line.

This simple test seems like a nice way to assess the presence of post-exertional malaise. If the grip strength remains normal, the participant can maintain the exertion. If not, they cannot. Note that this all appears to be taking place during anaerobic energy production. No, or little, aerobic energy production is required and its not clear how any conclusions drawn during a hand grip test could apply to aerobic exercise test results.

While the ME/CFS patients’ grip strength at the outset was normal, their grip strength rapidly declined. The fact that they exhibited a significantly lower number of “non-fatigued blocks” indicated that they lacked endurance, and suggested they had reduced “fatigue resistance”. That didn’t happen in the healthy controls.

This pattern – a normal maximum grip strength but an inability to maintain it for long, suggested to the authors that the reduced “fatigue resistance” was not due to problems with the muscles themselves but was caused by the brain.

Hand grip strength has been found to be reduced several times, however, in past ME/CFS studies. In fact, hand grip strength was so reduced in one study that the researchers proposed that it be diagnostic for ME/CFS.

Bad Motor? The Mortor Cortex Takes Center Stage

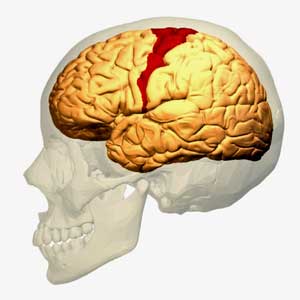

A transcranial magnetic resonance stimulation (TMS) done during the handgrip exercise suggested that problems with the motor cortex were to blame. The motor cortex is responsible for activating the muscles during exertion.

Not only does the motor cortex tell the muscles to activate during exertion, but a fibromyalgia study suggested it may also play a role in pain.

When we engage in any physical task, the primary motor cortex in our brain activates the motor neurons in our spinal cord, which then sends a signal to the neuromuscular junction of the muscle telling the muscle to move. As a muscle fiber becomes fatigued, more muscle fibers are recruited. So long as new, fresh muscle fibers remain to be recruited, the exercise can continue. If no muscle fibers are left to be recruited, or if the brain has a problem recruiting new muscle fibers, fatigue sets in.

In TMS magnetic fields are used to assess the effectiveness and integrity of the connection between the motor cortex and the muscles. (They do this by assessing the amplitude of the motor evoked potentials (MEPs). In healthy people, and in people with depression, the amplitudes fall over time during exertion, but in the ME/CFS patients, the motor cortex remained activated, resulting in, in the author’s words, “reduced motor engagement”. It was as if the motor cortex kept pushing the ‘on’ button in an attempt to get the muscles engaged. In the ME/CFS patients’ case, the overactive motor cortex exhibited what is called increased “corticospinal excitability”.

This was an interesting finding because one might have expected the opposite. Increased corticospinal excitability is more often associated with increased endurance. People who expect to experience high amounts of pain, and people with a fatiguing and painful case of multiple sclerosis, exhibit reduced corticospinal excitability.

These researchers found increased corticospinal excitability, however. Increased corticospinal excitability has been found in diseases like migraine – a common comorbidity in ME/CFS – and epilepsy. A recent study found that hyperventilation – an common problem in ME/CFS – can be associated with increased corticospinal excitability as well.

The authors proposed that:

“the fatigue of the ME/CFS participants is due to dysfunction of integrative brain regions that drive the motor cortex, the cause of which needs to be further explored. This is an observation not previously described in this population.”

Past Motor Cortex Findings

While most studies have not assessed the drivers of motor cortex dysfunction in ME/CFS, the motor cortex has shown up in ME/CFS and fibromyalgia before.

A 1999 study, which found a reduction in “premovement” brain activity and slower reaction times, concluded that the “central motor mechanisms” that lay the groundwork for an accompanying movement were impaired in ME/CFS. A 1999 study came to the remarkable conclusion that “an exercise-related diminution in central motor drive” was present; i.e. the brain was having trouble driving the muscles in ME/CFS. A 2001 study found it was harder to get the brain to cause the muscles of people with ME/CFS to react. Another study (2003) suggested that problems in “motor planning” are present.

A 2003 study, “Deficit in motor performance correlates with changed corticospinal excitability in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome“, suggested that reduced muscle recruitment due to reduced motor cortex output might be the cause of the fatigue in ME/CFS. That study suggested that “… changing motor deficits in CFS have a neurophysiological basis [which] … supports the notion of a deficit in motor preparatory areas of the brain“.

In a fibromyalgia study, the motor cortex activity (oxyhemoglobin content) was similar between the people with FM and the healthy controls at rest, and during slow tapping, but when asked to tap rapidly, the activity in the motor cortex of the FM patients faded (and so did their tapping ability). It didn’t seem to have the metabolic wherewithal to keep up with the healthy controls.

The motor cortex issue, then, makes sense with what we’ve seen before. In a way it’s a perfect explanation for ME/CFS.

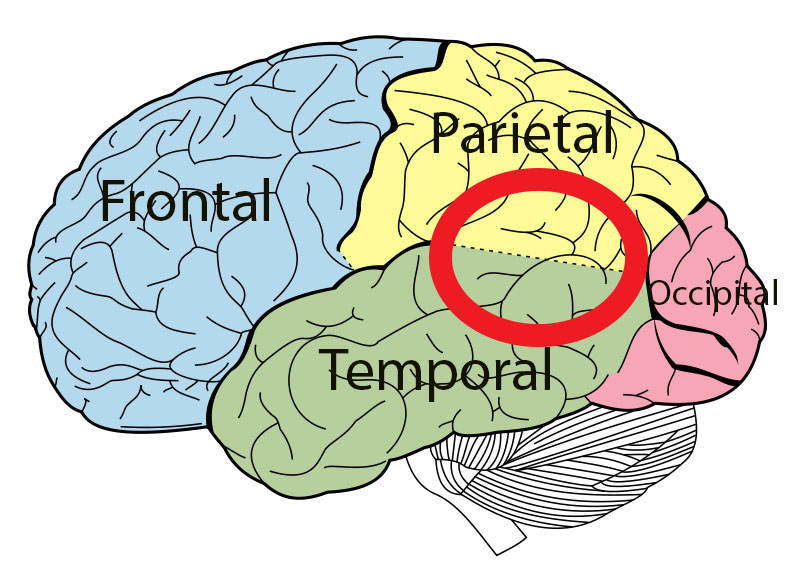

The Weird Temporoparietal Junction

(This is a long and difficult section where I struggled, sentence by sentence, to understand what the authors meant. You might want to skip to the GIST :))

Seeking to get at what was happening during the hand grip test, the authors then assessed blood oxygen levels in the brain. In contrast to the healthy controls (whose blood oxygen levels increased), the blood oxygen levels decreased in the ME/CFS patients in three parts of their brain – the temporoparietal junction (TPJ), the superior parietal lobule, and the right temporal gyrus.

The TPJ – the part of the brain they focused on – has never shown up in ME/CFS before – but then again, no one has ever imaged the brain while doing a handgrip exertion – and here’s where it starts to get a little weird.

The TPJ is a rather bizarre organ the authors had to try to make sense of. It has been associated with things like disembodiment, self-conscious emotions, others’ beliefs, and socially guided decisions. It is also, though, an organ that “makes predictions on states of the environment with actual outcomes”.

That little effort preference finding – which made total sense – why expend effort when the cost is high? – got looped into the temporal parietal junction finding – and one had the sense the authors either had a difficult time making sense of it or had a difficult time explaining it.

The effort preference finding showed up early and prominently in the discussion section. The first sentence states: “Effort preference is how much effort a person subjectively wants to exert.” While the paper has been focused on the brain, now the authors are referring to how much a person subjectively wants to exert, as in, what you, a thinking human being, decide you can do. We just seemingly moved out of the brain and into psychology. It goes on:

“It is often seen as a trade-off between the energy needed to do a task versus the reward for having tried to do it successfully. If there is developing fatigue, the effort will have to increase, and the effort:benefit ratio will increase, perhaps to the point where a person will prefer to lose a reward than to exert effort. Thus, as fatigue develops, failure can occur because of depletion of capacity or an unfavorable preference.“

So is it a depletion of capacity? The answer is no – the authors believe the muscles have the capacity to do the work. Why do they think that? Because the muscles were able to produce a suitable maximal grip strength, muscle mass was normal, and they found no evidence of changes in muscle twitch fibers. Plus, they found no evidence of problems in “ventilatory function, muscle oxygenation, mechanical efficiency, resting energy expenditure, the basal mitochondrial function of immune cells, muscle fiber composition, or body composition”. Note, though, that quite a few other studies, including a recent one, have found evidence of muscle dysfunction in ME/CFS and two major muscle biopsy studies are underway at the Open Medicine Foundation.

So, the problem has to be – according to the authors – “an unfavorable preference” – which the authors linked to a recent hypothesis regarding the activity of the temporal parietal junction. Besides all the other bizarre things the TPJ has been associated with – which have nothing to do with ME/CFS – it is also an organ that “makes predictions on states of the environment with actual outcomes”.

The “actual outcomes” when it comes to exertion are, of course, really problematic when it comes to ME/CFS. Since ME/CFS patients themselves don’t know how to assess the effects of their exertion – sometimes they can tolerate it and other times they can’t – it seems to make sense that a brain organ that “makes predictions on the states of the environment” might be having problems. Perhaps a damaged TPJ doesn’t know what to do when it comes to exertion.

Could the effort preference and TPJ findings reflect the difficulty people with ME/CFS have in making their way through an uncertain environment?

One hypothesis concerning the TPJ (and there are many) suggests that decision-making “is an optimization problem aimed at minimizing the variational free energy”. Minimizing free energy implies selecting actions that reduce uncertainty about future outcomes (a big, big problem in ME/CFS) while maximizing the desired outcomes. Given their uncertainty about what will happen, people with ME/CFS have tremendous problems deciding whether to go for the “desired outcome” (i.e. a trip to the store, seeing friends, going on a walk, going to a doctor’s appointment) while minimizing uncertainty. The best option often is simply to discard the desired outcome.

Then came this bizarre sentence. “Greater activation in the healthy volunteers suggests that they are attending in detail to their slight failures, while the ME/CFS participants are accomplishing what they are intending.” (???)

THE GIST

- The 8 million dollar NIH-funded study was perhaps the most important ME/CFS study for one simple reason – if successful, it would give the biggest medical research funder in the world the confidence to devote more resources to the disease.

- The study involved two week-long stays at the NIH’s clinical center where participants got just about everything the NIH could throw at them. The projected 80-person study, however, was curtailed by the pandemic. By the end of the study, 41 participants (17 ME/CFS patients and 24 healthy controls) made it through the study. Plus, sometime after their participation in the study, 4 of the ME/CFS patients spontaneously recovered – suggesting that, in some crucial way, they may have been different from you or me.

- A simple hand-grip test where the participants were asked to squeeze and hold a hand grip while the researchers assessed brain functioning turned out to play a major role in the paper. The ME/CFS patients had normal handgrip strength, but they faded quickly and their grip strength rapidly declined.

- The authors proposed that the problem was not in the muscles but in a part of the brain called the motor cortex. During exertion, the motor cortex stimulates the nerves to recruit more muscle units as a muscle becomes fatigued. The motor cortex in the ME/CFS patients was abnormally activated – indicating perhaps that it kept trying, to no avail, to activate more muscle units and stave off fatigue.

- The authors asserted, “the fatigue of the ME/CFS participants is due to dysfunction of integrative brain regions that drive the motor cortex”. Motor cortex dysfunction could, then, explain a lot of the problems with exertion in ME/CFS. While motor cortex dysfunction has not played a prominent role in ME/CFS research, at least four studies/papers have proposed that it’s present.

- Seeking to get at what was happening during the hand grip test, the authors then assessed blood oxygen levels in the brain. In contrast to the healthy controls (whose blood oxygen levels increased), the blood oxygen levels decreased in the ME/CFS patients in a part of the brain that’s never shown up in ME/CFS before – the temporoparietal junction (TPJ).

- The TPJ is a rather bizarre organ the authors had to try to make sense of. It has been associated with things like disembodiment, self-conscious emotions, others’ beliefs, and socially guided decisions. It is also, though, an organ that “makes predictions on states of the environment with actual outcomes”.

- The “actual outcomes” when it comes to exertion are, of course, really problematic when it comes to ME/CFS. Since ME/CFS patients themselves don’t know how to assess the effects of their exertion – sometimes they can tolerate it and other times they can’t – it seems to make sense that a brain organ that “makes predictions on the states of the environment” might be having problems.

- An effort test (EEfRT) – which also has never been done in ME/CFS – found that people with ME/CFS tended to choose the easy task over the hard task more often, regardless of whether the reward was high or whether it was likely to occur. Since ME/CFS is, by definition, effortful, one would expect people with ME/CFS to have low EEfRT scores, and indeed they did.

- The TPJ finding, combined with the effort finding, combined with the lack of findings suggesting that the muscles were damaged suggested to the authors that “effort preference” was the defining cause of the “motor behavior” in ME/CFS – the motor behavior being the inability of the motor cortex to activate the muscles.

- It was hard to understand exactly what the authors were thinking, but it may have been something along the lines of: when faced with effortful tasks such as exercise, the motor cortex stops signaling the muscles, thereby inducing fatigue. This would work on a subconscious (brain shuts down motor cortex) and possibly conscious (avoidance of effort) level.

- Not surprisingly, some of the media articles on this part of the study sound a bit psychological while others did not. On the whole, the media response to the study was quite good.

- There’s much more to come, though, and part II of the blog series is coming up.

In that context, motor behavior” could be something like “sickness behavior” – a brain-derived condition that produces all sorts of symptoms and problems in an attempt to keep the body as well as possible. Suffice it to say that motor behavior is a broad and general term that “includes every kind of movement from involuntary twitches to goal-directed actions, in every part of the body from head to toe”.

It’s no surprise, given how hard it is to understand what the authors meant, to see the interpretations of that part of the paper get muddy.

The Media Response

We can make too much of this part of the study. The media response to the study was positive and did not dwell on it. It’s more an issue for us as a community given our history.

That was good because even Brian Walitt, the lead researcher of the study, spoke inartfully about this part of the study. The NIH Press Release started off fine stating “This suggests that fatigue in ME/CFS could be caused by a dysfunction of brain regions that drive the motor cortex, such as the TPJ” and so did Wallitt “We may have identified a physiological focal point for fatigue in this population”, before he unfortunately opened the door to a psychological interpretation by bringing “thinking” into it, stating, “Rather than physical exhaustion or a lack of motivation, fatigue may arise from a mismatch between what someone thinks they can achieve and what their bodies perform.”

One would have thought Walitt would have been more careful with this topic. In my experience, this is a brain issue – not a thinking issue. The fatigue, pain, etc., signals come so fast that they must come from the brain. Two media outlets thus far have picked up Walitt’s maladroit statement. It’s quite ironic how often people with ME/CFS think and feel they can do something only to find out midstream that they’re in real trouble.

The Medical Express got it right:

“The study found that as they did the hand grip test the ME/CFS showed decreased activity in their right temporal-parietal junction, a brain region involved in self-agency. This is a part of the brain whereby the brain predicts an action before one becomes consciously aware of it.”

So did Nath in the Scientific American

“Nath hypothesizes that this dip in activity suggests the brain is cautioning people with ME/CFS against exerting force during the grip test, which he says makes sense because ME/CFS symptoms often intensify if people with the condition overwork themselves. The finding is preliminary, however, and further experiments are needed to corroborate it.”

Jonathan Edwards, a rheumatologist at UCL, got it right in the Science article

“The researchers suggest brain signals may flash stop signs to prevent physical activity—similar to how a bout with illness forces rest. “When we have a bad flu, [we] can’t get out of bed,” “It’s a central signaling problem” in the brain, he says. “There’s nothing wrong with your muscles.”

And Tony Komaroff hit the nail on the head in two media outlets:

“ME/CFS patients also had abnormal functioning in a part of their brain that governs effort. When they are asked to exert themselves, it doesn’t light up as much. It’s like trying to swim against a current.” and “That brain area, the right temporal-parietal junction, is involved in “telling the legs to move, telling the mouth to open and eat — it sort of says do something, When it doesn’t light up properly, it’s harder to get the body to make that effort”

As it turns out, in the paper’s proposed model for ME/CFS, the TPJ doesn’t appear to play a prominent role. The authors believe the TPJ dysfunction is caused by other factors but that’s for the next blog. There’s a lot more in this study to chew on.

- Next up – Pt II: Exercise, the Immune System, and the Really Big Picture

I call BS

Thanks for chiming in but what we really want to know is what part of it you think is BS and why.

Merci Cort. The brain trying to minimize the effort in order to survive. I believe this strongly and this article will encourage me to pay even more respect to what my brain is saying. The minute it tells me « we are tired » I will put us to rest. It looks like the scientific explanation of why pacing works.

I’m going to quote Cort’s gist first: “when faced with effortful tasks such as exercise, the motor cortex stops signaling the muscles, thereby inducing fatigue. This would work on a subconscious (brain shuts down motor cortex) and possibly conscious (avoidance of effort) level.”

That part of the study reeks of ‘people with ME are scared of exerting themselves and if they just didn’t think about it they wouldn’t experience fatigue.’ Ummm, no. And ME fatigue is WAY MORE than rapidly declining grip strength! I was intrigued initially because that exact thing happens to me in daily life but using it as a definitive fatigue test was a bit strange to me. And i agree with what others have written here that of course some element of this is people with ME intentionally (consciously or subconsciously) choosing easier task regardless of reward… like yeah we do that every day to survive!! So in my opinion the result there is just showing ingrained pacing, not some novel facet of the disease…

This study design and interpretation were concerning to me.

Absolutely agree with you. PEM is a core feature of ME/CFS, post exertional worsening is exactly why people have trouble pacing activities to recover. To exclude people with it makes the whole study moot, never mind the problems with how they used CPET. I asked in another comment why people with myositis were excluded. How do we know myositis is not a downstream effect of ME/CFS?

The recent REGAIN study for Long Covid also used people who had no PESE (post exertional symptom exacerbation). They used people who still worked, who did not really have the symptoms that cause long term disability, so of course they will find that a positive attitude and graded exercise therapy can be helpful… those things are helpful when one does not have ME. Is this deliberate?

I don’t understand this idea that the people in the study did not have post-exertional malaise. All the ME/CFS patients in the study were vetted by ME/CFS experts like Lucinda Bateman, Dan Peterson, Tony Komaroff, and Benjamin Natelson before they could enter the study. I think those doctors know what an ME/CFS patients is and what PEM is.

As one of the 17 ME/CFS study participants, perhaps I can roughly describe my level of functioning during the study for some additional information. I arrived in a wheelchair as that’s the only way I could leave our home at that time. After about 3-4 days of testing during my first visit, I was only able to get to more testing on a stretcher, had to use a bedpan, and couldn’t sign the consent form myself before the spinal tap. After the 10 days of testing, I had to stay a couple of extra days to recover enough so I could be in our van as flat as possible to get back home, while wearing Depends since I could not get out to use a bathroom during the drive back. We had to cancel my flight back as there was no way I could have sat upright on a plane. Given what the research team observed during my first visit and after being unanimously adjudicated, they suggested for me to return for a modified second visit protocol since it was not possible for me to do a CPEt and then stay in a metabolic chamber without assistance for the next 24 hours. Therefore, I returned for another two-week stay but without the CPEt. There is no way I could have attempted a 2-day CPEt. My husband had bought an air mattress, so I rode the last part of the drive home laying flat in the back of the van as even being reclined as far back as possible was not enough. I had to call my husband to come home from work every time I had to use the bathroom while I recovered at home afterwards, as I could not get there or sit up for even a few moments by myself at first. This is only one of the 17 participants, but perhaps it adds some helpful information for some.

This resonates with me. As someone with both ME CFS and ADHD- I thought for years that my ADHD had gotten incredibly worse- then I realized that the increased ADHD-like symptoms were actually ME CFS symptoms. ME CFS has resulted in becoming very out of shape- but I always still feel that I’m essentially physically able and could easily get back in shape if only I could function, and the reason I can’t function is because of something that’s going on in my brain. And yes, of course decisions about what we can tolerate changes situationally- it depends on the whole of whatever we have to deal with at any given time.

ADHD appears to be hugely increased in ME/CFS and FM. I really wish researchers would look more into this – there are nuggets to be found there.

If you look at the GIST more carefully I think you’ll see you added stuff that is not in it.

“cared of exerting themselves and if they just didn’t think about it they wouldn’t experience fatigue”’

The motor cortex comes BEFORE thinking. You can’t tell your motor cortex to stop transmitting signals to your muscles. You don’t have any voluntary control over that.

Ingrained – deeply ingrained pacing – like the brain telling the muscles to shut down because it senses something bad is going to happen – that’s more like it.

“Ingrained – deeply ingrained pacing – like the brain telling the muscles to shut down because it senses something bad is going to happen – that’s more like it.”

Cort, that is the very definition of Functional Disorder. The treatment is then to retrain your brain to stop the unconscious pacing. You know from my long history of commenting on this site that how unafraid I was but frustrated by repeated PEM (that I used to describe as a fly running into a brick wall over and over again). We are getting into a dangerous territory of sociopsychobiology if we buy into this notion that MECFS patients are dysfunctional because of they are afraid of PEM.

It’s funny one journalist likened it to flu saying something like ‘there’s nothing wrong with your muscles when you have flu, the weakness is a central signalling issue’.

Weeeellllll, kind of. The fundamental issue is you have the flu, you’re very sick and your brain and body respond to being very sick by behaving exactly how they should when you’re very sick. It’s not like your brain is dysfunctional when you have the flu and it’s also not like the signals to rest are only coming from your brain. In addition to brain signalling your entire immune system is activating in a decentralised way fairly independent of direct brain control.

It kind of seems this TPJ stuff, combined with the immune activation stuff they found is just a very round about way of saying ‘these people are sick and their bodies and brains are responding like they’re sick, so they seem to observers to be sick.’

I also think it is not good that this study received so much mediat attention (and that these researchers got so much money) – because they are simply in denial of a lot of very well established facts on ME/CFS.

We’ve already had enough evidence that there is a problem with mitochondrial function (not only in the muscles) already back in 2019 that explains the pathological exhaustion. Below is a well written summary of those findings. And it’s only grown since then.

https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&cad=rja&uact=8&ved=2ahUKEwjr5JD3g8SEAxVC_bsIHWlcAsYQFnoECBEQAQ&url=https%3A%2F%2Fmeassociation.org.uk%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2FMEA-Summary-Review-The-Role-of-Mitochondria-in-MECFS-12.07.19.pdf&usg=AOvVaw2euTHSafLmVrfMuu_Q9ca6&opi=89978449

I hope there will be some decisive reply from other researchers making the media and the public aware of that.

the problem with the mitos is a downstream consequence

Let’s note that the paper declared that MECFS is neither muscle fatigue nor central fatigue, but it is “centrally mediated”. Let’s also note that the fatigue from flu is a central fatigue. From this, we can deduce that the paper is saying that MECFS is all in the brain (centrally mediated), but not physiological (central fatigue). It’s more like they are saying MECFS is functional disorder.

The paper also found catechol level correlating to the performance. No idea where they’ll be going with this, but I sure hope that they are not headed to “MECFS is a form of depression”. Both dopamine and norepinephrine are chemicals associated with motivation and activity which depression patients lack. EEfRT test are commonly used to diagnose depression as well.

All of it. It’s farking bullocks as a friend from Scotland used to say. What we know is that this sheet starts with most cases herpesvirus and less commonly Lyme or some other micropredator organism. And it screws up the t cells. And there are elevated cytokines and messed up complement system and epigenetic changes. After that our bodies are just farked up everywhere, brain gut muscles mitochondria and everywhere else. So yeah maybe there’s a pie in the sky line in the brain that gets a bit out of balance and the environment is perceived a bit differently. But I can tell you that the difference on certain drugs which modulate the immune system makes it very clear that it is not a brain problem at its root. It may end with messed up brains but its an immune system problem for sure. What is the one cancer that is increased in ME/CFS? immune cell cancers. Duh!!!

I have some concerns too (though as usual thanks for the great article Cort).

I know that serious researchers have been involved in this (to say the least), but this is hard to not interpret as being “both original and good”. That is, the original parts aren’t good and the good parts aren’t original. After $8M, based on an N = 17, looking at the pathophysiology diagram, I can’t help but feel that the “effort preference” stuff is a less than an impressive “novel finding”. It certainly appears to inadequately address/incorporate PEM. Subsequently I have some correlation versus causality doubts. At a mild/moderate level of illness, at rest, PEM feels like a combination of having just completed a marathon and having a cold. If you started the healthy controls from roughly the same state before completing a grip test (like just after the healthy controls ran a marathon), I wonder if their results would be significantly different to those for PI-ME/CFS? I might have missed something, but is the brain just doing what it does when people are wrecked, or is it wrecking the people?

Other curiosities:

– PEM wasn’t measured using existing gold standard biometric approaches – money and time? “Interviews with PI-ME/CFS participants revealed that sustained effort led to post-exertional malaise” – wow!

– Finding sub-sample sizes – the repetitive grip testing is based on n = 8! I’m sure the healthy controls weren’t all brick layers and rock climbers, but the data set seems so tenuous a result to then derive a new pathophysiology hypothesis.

– The fact that 4 people spontaneously recovered out of 17 within 4 years – isn’t that more than double that standard 3% spontaneous remission rate? Shouldn’t that be a selection process red flag?

The “effort preference” proposal could be interpreted as a far a more expensive version of the same old nebulous, small sample size, going nowhere research findings that have plagued ME/CFS for a long time. It would be great if these all turn out to be the most foolish things I have ever thought, but I started reading the article with the hope of being compelled and that certainly didn’t happen.

Thanks Lono. I read that the CPET study didn’t have many participants either. I’m going to look into that more for the next blog. That is a very small number to hang a hypothesis on. What a shame this study was so truncated.

I found the study protocol details on the NIH website:

https://clinicalstudies.info.nih.gov/protocoldetails.aspx?id=16-N-0058

It reads that having PEM was required for phenotyping portion of study

but having PEM was not required for hand grip portion of study

I thought that might point to why only 8 were in the hand grip data

I also wondered why they didn’t care if you had PEM for the hand grip test

That being said, if you review Source Data file #5 from yesterday’s publication, it says 100% of the PI participants meet the 2015 IOM diagnostic criteria for ME/CFS, which requires PEM. So now I am back to wondering why only N=8.

Check my work bc reading this stuff really makes my brain foggy.

Nice digging! Thanks!

Cort where do you begin? I’ve done biological research for over twenty years with over fifty publications and I have reviewed regulatory submissions for hundreds of medical products. I’ve sat on NIH review panels too. The thing I see over and over is that you have to distinguish primary causes from secondary effects. If you don’t, you still be measuring secondary effects forever and never get to what caused the problems in the first place. Long COVID should have made this clear. You have people who were recovered from ME/CFS or mostly recovered who got much worse than ever before when they got covid. That is not a brain disease at root cause. It is an immune system problem at root cause. Watch Pattersons trial of maraviroc and atorvastatin for long COVID. Look at the pet scans of activated t cells. Study recent papers on exhausted t cells. They point to the immune system, not the brain, as the root cause.

I can say from experience with long COVID that maraviroc took me from anxiety, depression, fasciculations, and tremors and weakness in five days to normal. I if a CCL5 inhibitor mab does that, it’s not the brain, it’s the immune system.

I had “mono” for a year after CMV infection at age 42 (I’ve never had EBV). It’s basically indistinguishable from getting CFS and recovering. Did I change anything about my thinking? No, I slept a lot because my body needed to rest to heal the immune system after fighting this sneaky and persistent micropredator.

Support the immune system to regenerate (it may take autologous cell therapy) , get rid of chronic infections ( through future herpes vaccines, Lyme vaccines, etc.) and damaged mitochondria/epithelial cells and you will cure me/CFS. Anything less may help but likely won’t cure

Stop NIH from wasting so much taxpayer money on these professors who study secondary effects! They have their heads buried in the sand.

In the end the authors posit that immune problems are driving the “brain disease” – that’s coming up in the next blog(s). Congrats on the progress!

Good luck waiting on these people while they keep up their “positing”. All this is going to do is lead to more headlines saying that long COVID is a brain problem which people will translate as a psychological problem.

I actually don’t think so! For one, the media is not portraying it this way. For another – wait for the next blog – it’s quite interesting!

I will be holding my breath (w. hof style)

🙂 🙂 🙂

I bet the root cause are squeezed veins in the brain. I had CFS/ME for 4 years and 6 months. And would bet on squeezed veins.

Dana, as one of the 17 study participants but not one of the 8 who completed the CPEt, I can say that for myself, my functional level as observed by the researchers during my first visit meant that I couldn’t physically do the CPEt and stay in the metabolic chamber for 24 hours without assistance afterwards. My memory is a little vague for this one, but I think the hand grip test was also something they kept pushing out because I was too low to complete it, and I don’t think we ever got to that. So, some of the low numbers might have been due to participants being unable to complete the tests. (See my comment above for more on my functional level.)

” is the brain just doing what it does when people are wrecked, or is it wrecking the people?” That is a great question and one that I think depends on the original circumstances that set things off. My suspicion is it’s a big cycle that also includes the rest of the body. We know the gut influences the brain and vice versa. There’s not much I can do to influence my brain, thanks to the blood/ brain barrier but I can control when and what I eat, the little exercise I can do and the rest and meditation to give my brain a chance to heal and re-sync with the rest of my body. It seems to be working with the help of Cort and everyone’s input on this website. I don’t expect to regain my youthful vigor but do hope to one day age “normally”. 🙂

Agreed, my BS alarm is ringing. First of all, they’re making pretty definitive statements with a miniscule n, the CFS cohort seems like they might not meet the usual criteria, and the amount of recoveries was suspicious considering the overall statistics.

They claim there’s nothing wrong with the muscles, but we know that isn’t true (biopsies are way more reliable than the metrics used in this study).

As well as the scientific concerns I have with this, the key piece I see missing is this:

Who here who was mild had a pre-diagnosis ‘denial/”im just lazy”/exercise will give me energy/im just burnt out’ phase? And did all the exercise before you’d figured out you were sick cure you? Let me guess, it made it worse (or of course you wouldnt be here.) If your subconscious was able to push you past your limit over and over, thats the exact opposite from your brain giving up too early.

One more note cuz i see a lot of people talking about brain retraining, remember that part of many brain retraining programs is saying that you feel better even if you dont. Many people also become spokespeople for these programs because they are trying their best to really believe in the program because they are told it would make that better. But that has led to a complete absence of reliable peer-reviewed or anecdotal data, which is a big problem! The lightning process for example, shows off all their studies that show almost unbelievable success… based on patient interviews. Interviews of patients who are instructed to say they feel better no matter what. It’s a predatory scam. (its a personal project of mine currently to try and get those studies retracted because they dont meet scientific standards.) PEM is a hallmark for a reason, be careful!

I’ve been waiting since yesterday morning’s breaking news to read your interpretation/translation, Cort. Thank you for always breaking these things down for us!

On a separate note, for the decade in which my ME was severe, I had no grip strength, which is why my doctors then were freaking out and trying to admit me to the hospital because I was so weak. But I could probably do that grip test for awhile, now that I’m moderate. I’m wondering whether the grip test came out that way because they did not have any severe patients.

That was my thought as well. If I remember correctly, the AI they used in a study was able to not only differentiate Me/cfs patients from healthy controls but also sub groups of severity of Me/cfs patients.

This might explain different findings in different studies.

Cool. Did you find that in the publications footnotes or a data file? I would love to read more about that

https://www.healthrising.org/blog/2023/09/09/blood-test-chronic-fatigue-syndrome/

It was in this article. I didn’t get deeper into it.

😍 exactly like me. Article published, look up for Healthrising Newsletter.

About Handgrip, Scheibenbogen et. al. developed another Handgrip test protocol which I also find better re PEM, with 2 rounds. And I prefer the device with “ballons” as many have problems with joints and pain can be a confounding factor. The ballons are “nicer” than the hard plastic devices

Wow! Finally scientific acknowledgement of a brain disease! Pw mecfs already knew that. Great to have brain dysfunction and where validated.

Can’t wait for part II !!

This is an amazing article. These problems in the aforementioned area of the brain might suggest how nervous system/brain retraining programs are successful for some the MECFS population. What do you think?

Yes, yes, yes, exactly what I mentioned in my comment!

In a study comprised of mild subjects and a conclusion based on misuse of CPET and excluding possible downstream myositis, the Effort Preference theory seems like a leap from a psychological angle to explain what other evidence would have.

If I am not mistaken, the same subjects were used in Yang’s article WASF3 disrupts mitochondrial respiration and may mediate exercise intolerance in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. Those subjects had abnormalities and ignoring that is a huge flaw. Ignoring that is what is necessary to blame brain signalling.

The subjects did not have to have PEM, and how many did not(?), so it’s doubtful whether they had ME/CFS at all.

What evidence is there to compare ME/CFS to a functional disorder other than ignoring other evidence? During the grip tests, blood oxygen level dependent (BOLD) signal of PI-ME/CFS participants decreased across blocks bilaterally in temporo-parietal junction (TPJ) and superior parietal lobule. Is it suggested that this is a semi-conscious decision?

We know anecdotally that some people with fatigue benefit from brain retraining. Perhaps it’s possible that those who do perhaps don’t have the same ME/CFS that we are trying to solve biologically? Interested to hear what Cort and others think, too. Will be an update coming.

Hannah, please see my reply to Dana above regarding one participant’s functional level.

Kathleen, I was thinking the very same thing. It’s maybe why so many of those who Raelan Agle interviews on YouTube have been able to recover over time. These are very real symptoms, but we have to steadily teach our brains that activity is safe. (I have been trying to do this and am not quite there yet).

Where are these ME/CFS documented? This is not a brain retrain disease. It does not explain the abnormalities in cardio-vascular, immunological, aerobic metabolism, etc.

It would be interesting to know if the patients who recovered had different results as a group to the rest of the ME/CFS patients.

Thank you for the prompt to skip to the Gist, btw Cort. I was automatically about to stretch my brain way too far but you put a stop to that!

It seems so far that the researchers have some interesting findings, but somewhat odd interpretations of them? Thank goodness the media coverage has been positive so far. And thank you for including info on the reception of the paper too!

“It would be interesting to know if the patients who recovered had different results as a group to the rest of the ME/CFS patients” – Great question! I want to see if they had ME/CFS for a shorter period of time than the rest.

Yes, the media reception has been quite good – and it really should have been. I wonder how far the “effort perception” thing will go. It was based on a test and brain imaging finding both of which were unique in ME/CFS literature. Then they had to dig deep into the TPJ – which is truly a bizarre and very complicated part of the brain – to come up with the mis/match idea. It’s very technical and complex and I wonder if its going to be taken up much.

The real takeway for me from this first part of the study was motor cortex finding. I’ve been wondering about that since Puri suggested it over a decade ago. It makes sense to me.

Perhaps those who recovered realized after the two weeks of exertion and not crashing after that more intense activities were actually safe. Maybe they convinced their motor cortex or the newly involved area of the brain that really this was okay. I have been convinced for a while that brain retraining can work.

Is it possible there is micro damage to the motor cortex? Does anyone know if this has been looked at with the right kind of specialized MRI?

Thank you for explaining this paper so thoroughly & comprehensively!

This paper was so confusing, the key points were lost.

Thanks!

Thanks Cort! Do you know if the researchers assessed exertion from mental tasks or things like having a conversation? I’m severe and often can’t talk much at all because it’s physically too much effort (it’s not a choice though, I would love to talk more but I try and can’t).

The hand grip results ring true in a way for me. If I try and hug my partner, I can manage a few seconds with my arms raised (if at all) and then I can’t manage any more. This is the same if I do something simple like hold a glass of water for too long as well.

The other results about choosing the less effortful route seems a logical adaptation that anyone with an energy limiting illness would end up making since brains are smart and adaptive. I hope there is no suggestion that we are somehow choosing the easier route and that’s why we’re ill because I don’t believe that is at all what people with ME experience. I hope the authors can bring some clarification to this since ME has had such a background of cumulative abuse that we really need people to understand what a horrific physical disease this is.

I’m pretty sure cognitive exertion wasn’t done. A really interesting Japanese study, however, found that taxing cognitive exertion in ME/CFS led to sympathetic nervous system activation that took much longer than normal to return to normal. The ME/CFS patients systems were basically put into a state of fight/flight.

https://www.healthrising.org/blog/2014/08/27/biomarker-fatigue-validate-chronic-fatigue-syndrome/

Wow I’m surprised it wasn’t studied. It feels like a huge missed opportunity given the scale of the study as cognitive exertion seems like one of the hallmarks of the disease.

Thanks for the link to the Japanese study. To me the findings fit with my experience of the disease and what others talk about too. Do you think cognitive exertion is an understudied area? I noticed the Japanese study was from 2014 and ironically I’m too brainfogged from reading to think of other studies that have focused on it!

Cognitive exertion has not been studied much but check this out. It’s from 2012 and is more on the autonomic nervous system response to cognitive exertion

https://www.healthrising.org/blog/2013/05/24/nervous-system-abnormalities-tied-to-cognitive-problems-in-chronic-fatigue-syndrome/

How about that!

Hi Cort, that’s a really significant finding, thanks for sharing! It absolutely makes sense to me from my own experience as whenever I’m worse, my autonomic system is far more out of control. It seems very easy to knock it off kilter but takes perhaps 4 days minimum to get back to where I was previously… I hope someone finds out why that is!

I’m also hopeful that now there seems to be more interest and funding for ME, that we might see more of these interesting and important studies replicated and followed up.

Thanks SO much for all that you do for our community, you make a massive difference to peoples’ lives!

This is me also. I am completely floored by cognitive and emotional exhaustion including stress and stressful situations. And this is also not a choice for me; it’s all subconscious. When in a flare from these activities, I can’t talk, eat, swallow, think, use professional language or walk and I just have to go to bed for as long as it lasts. And it is not an exhaustion I have ever experienced before or can fully explain. I feel like I’m in a coma; I can sometimes hear what’s going on around me but I cannot respond.

That’s exactly what happens to me too and I often liken it to a coma as well! I know another ME sufferer who gets the same thing also.

I don’t know if you do also, but I get a kind of mild version of this after ‘waking up’ – I say it like that because it seems like my body actually takes around 2hrs to properly wake up and the first 30-60mins my body can’t really move. It’s not distressing like it is in a crash, it’s as if I’m just not properly out of a sleep state yet. I used to get sleep paralysis (pre-ME) and again, it’s weirdly similar. I looked up the mechanisms a while back and felt there were some themes that chimed with ME research but can’t remember what they were now but I really think there’s something in it.

Having a conversation is hard for me too.

I don’t know how much of that is caused by physical changes to one vocal cord* and how much of the problem is mental exertion/(“positive stress.”

An ENT observed “vocal fold paresis” 5 years after late, disseminated Lyme/Bartonella was diagnosed.

Then a neurologist said my laryngeal nerve was probably damaged by those infections.

I sound fine to others, but speaking is exhausting and debilitating.

Now “Long Covid” exacerbates all of the CFS issues, including laryngeal dysfunction.

I have always said that when I crash my brain is on fire.

I’ve said similar as well, and it honestly makes me think the itaconate shunt theory is the winner. The part of that theory that involves ammonia getting released into the brain is exactly how the brain on fire thing feels to me.

Mine too. However, the scientists that are involved in this study don’t understand that. These researchers don’t seem to have read up about the findings on ME/CFS and diagnostics that we already have.

Your not the only one who has their brain on fire during an inflammatory episode. Have a look at the research about the theory of smoldering herpes virus brain inflammation (“abortive reactivation”).

Here is a summary and an overview on all the successful reseach that has been done on this question. They were even already able to prove their hypothesis in a small sample of brain tissue that was donated from ME/CFS patients who have died.

https://meassociation.org.uk/2023/01/research-review-reactivation-of-human-herpesviruses-and-their-role-in-me-cfs-and-long-covid/

It must be vains.

I can’t agree more. My head feels like it is burning. Sometimes, I like it to feeling like putting your head out the window of a moving car. It’s like roaring of wind, inside my head. It keeps me from being able to understand or respond to conversation.

Perhaps what you quoted here provides the key to interpreting those “inartful” statements made by the study. (I love that “inartfully” of yours — a great term which I suspect you may have inadvertently invented — and it works!!!):

“Nath hypothesizes that this dip in activity suggests the brain is cautioning people with ME/CFS against exerting force during the grip test, which he says makes sense because ME/CFS symptoms often intensify if people with the condition overwork themselves. The finding is preliminary, however, and further experiments are needed to corroborate it.”

In other words, the ME/CFS test subjects are doing what they are advised to do by the brain and not doing what they might be physically capable of doing, AT THAT VERY MOMENT. And this seems to me very sensible on the part of the brain. However, for most of us it will take a long time to learn to be this cautious. So wouldn’t that change in our “thinking” derive from the brain’s hard-earned experience of horrible delayed results from repeated exertions?

But here’s the maladroit statement you zeroed in on:

“Rather than physical exhaustion or a lack of motivation, FATIGUE may arise from a mismatch between what someone thinks they can achieve and what their bodies perform.”

This is so weird!

1) Fatigue is precisely the WRONG word here, since the muscles are shown NOT to be fatigued AT THAT TIME.

2) And the mismatch is precisely NOT between “what someone thinks they can achieve” and “what their bodies perform.” It is a MATCH between what someone’s thinking is telling them not to continue doing and what their body might be physically able to perform AT THAT TIME.”

You’re right, Cort — maybe the researchers just can’t write or communicate well. Otherwise, how could Nath and others have gotten what the study suggests right?

p.s. So, it seems that the brain doesn’t forbid us from doing one maximum hand grip. But the warnings begin to inhibit the exertion, the more we consider repeating the action? This shows that the brain has learned — has acquired — over time, a very accurate sense of what the delayed outcomes of repeated exertion are likely to entail. This is very good thinking. Objective thinking, we might say. Or so it seems to me.

I think I meant a MISMATCH between 1) our brain’s objective overriding of the decision to keep repeating the action and 2) the actual physical ability of the body to do the action AT THAT TIME.

Really a nice explanation, Janet – thanks! Maybe this explains that weird sentence – where the HC’s were paying attention to the details of their small failures while the ME/CFS patients were doing what they could?

Nice wording Janet. “at that time” the body can do the task, but the brain has learned that to do so will be huge mistake.

In my case it doesn’t hit till 48 hours later and my body feels like I got hit by a truck. Why is my calf muscle completely cramped up, if my brain is just sending out “be lazy” symptoms?

Thanks again, Cort. After seeing a few articles about this, I was afraid that it was small sample size, and same-old same-old. That was surprising, because Dr Nath has great credentials.

But no! It does sound like new investigations; and perhaps rigorous enough to get past the small size.

Dr Nath has done post-mortem work on brains of Covid patients, and had significant findings; so I was hoping that this investigation would include brain imaging. Maybe next time. . . .

Thanks again! You’re an ace.

I REALLY appreciate the work Nath is doing. I think he did get caught by the pandemic and the decision to wrap things up with the ME/CFS study. The fact that he was able to find some abnormalities even with that small group should tell the NIH a lot is going on in ME/CFS….I really liked the motor cortex findings 🙂

Hopefully, he can get the entire long COVID study – which was built off of this one – done.

Yeah! I love the structure of the long Covid project: specialties consulting, working together—truly a whole-body approach. And it seems like a really great team. I just hope that there’s patience to let the work find its way. Go Dr Nath! Go team! Go Cort!

Hi Cort. Interesting that some very critical responses to this study on twitter focus on Brian Walitt’s authorship and past controversy around his work, while your perhaps more nuanced take seems to focus on Avindra Nath’s involvement. Anyhow your work is much appreciated as always in helping to make sense of all this!

Walitt is a flash point and he threw himself right into it unfortunately. Everyone involved that I talked to – only a few actually – had nothing but good things to say about him. My understanding was that he was not doing the research; instead, he was coordinating a very, very complex project.

The neuroscientist who interpreted the brain/handgrip stuff and the effort test was responsible for that part of the paper.

From what I remember, Walitt was present during/conducting at least two of the major tests for me (tilt table test and functional MRI). He regularly checked on me and also completed the long background interview that lasted about 3 hours on a Sunday. He always took his time and was available if needed. I felt like I could always reach out to him and still can/do. I was amazed at how much he seemed to care and be involved at every level.

Does it makes sense that the brain tells you to stop making effort if it has experienced the body getting PEM? I experience this as a brain/central nervous system disease.

I have fast twitch muscles and come from an athletic family. My grip strength and reflexes measure very well, but I would guess tire out faster than normal.

I hope something useful comes from this study because I’m aging out of a future.

Interesting because I’ve noticed that my reflexes are still very fast as well. maybe something someone should look into?

It just dawned on me, well, 10 min later, that I’m pretty sure fast twitch muscles are controlled by the CNS/ spinal cord not the brain. Maybe that could be a way to determine if it’s really the muscles themselves that are fatigued or the signaling from the brain that’s messed up?

In my experience, I build muscle really quickly. When it’s built up, I’m stronger than a peer my age (and many younger). But what then happens is the muscles contract and cause chronic acute pain. Could be because of EDS? The only way to avoid that is to not use my muscles much. Then I’m in a balance of fitness vs. lack of pain and there is no good balance that I’ve found. Every one of us is different because of our peculiarities.

“A non-fatigued block occurs when the grip strength is above 50% of the maximum grip strength. A fatigued block occurs when the grip strength remains above 50% of the maximum grip strength.” Is this a typo or is my fatigued brain missing something? If so please explain.

🙂 There is a mistake there. It should be a fatigued block occcurs when the grip strength is below 50%.

Thanks! And your explanation of the weird TPJ was excellent! I followed that perfectly but the “fatigued block” part was just not computing. 😉

Did this NIH study explain PEM at all? (the defining symptom of our illness, which we constantly suffer because none of us want to be staying home and lying in bed all day every day). As an MECFS patient, I believe the points identified in this recent Muscle Abnormalities report for Long Covid could apply to us as well. Now that would be something helpful to study and fix… https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-023-44432-3

They did do an exercise test and were planning to do two exercise tests so PEM was part of the game. I’ll try and find out what happened with that.

Funny story: During my second round of CFS, the first was 20 years prior while in college, I remember telling my Primary Care Doctor about an incredibly odd sensation I felt one night while alone.

I was sitting in my living room and suddenly felt the very top of my head being hot. I immediately put my hand on my hair to see if the scalp was warm, which it wasn’t. So I knew the feeling was on the inside of my skull. It wasn’t a migraine or a headache I perceived but a distinct sensation of heat.

He pretty much laughed it off saying there’s no room in the skull for the brain to swell, and left it at that.

“silly patient, my years of experience as a Doctor has taught me to disregard all patient symptoms! If I can’t see it on a blood test, if doesn’t exist”

I fully believe that CFS would be much less emotionally destructive, if Doctors didn’t exist. Being gaslit is very painful.

I knew what I experienced was real and wasn’t hindered by his ignorance one bit. If I was a Doctor I sure wouldn’t respond to a Patient like that, though.

And that temporary, localized brain bake (as opposed to a brain freeze) never happened a second time.

Weird.

This is a great summary Cort. I think it is unfortunate that so much of the study was about this one region of the brain and this hard to understand effort preference.

I think 1. We can’t infer a ton from this because of the small sample size and very very narrowly-selected population;

2. This has the potential as you noted to be very easily misunderstood by people who might think this means that people with ME/CFS are just psychologically choosing to be fatigued and choosing not to do things even though they could;

3. I would rather see more investigation about what parts of the disease process are causing damage leading to these brain changes, i.e. how did we get there – we see so many studies that just add piecemeal observations that we don’t know whether they are manifestations of the illness or underlying pathophysiological causes and since these patients were closer in time to the infectious trigger it would have been cool to see maybe more of that.

5. As someone originally diagnosed with CFS that then was diagnosed more accurately later with FM when the pain showed up, I wonder if these are both post-infectious illnesses that start off the same in some way damaging the nervous system but that diverge somewhere for whatever reason in the specific phenotype and symptoms that manifest. I am happy there is more research being done in ME/CFS but frustrated that fibro is being ignored and that we still don’t have good answers on how similar the two are and exactly where there is overlap.

I do appreciate your efforts to bring in historical context for overlapping findings from fibro in these articles too so thank you.

One other point as I read everyone’s comments – I am not sure about this brain theory precisely because if the brain is somehow preventing ME/CFS folks from hand grip after repeating it, because it somehow adaptively learned not to overexert due to consequences, then why have all of us had the experience of pushing “mind over matter” and doing things WE KNOW we will pay for later but ignoring that and doing it anyway only to crash? To me that counters their entire hypothesis. I think the brain sends us signals like fatigue and pain in the first place as a way to get us to stop doing things it is perceiving as causing harms and the need to rest/heal, but since we can clearly override that I don’t see how there is this other mechanism at play that is deciding to shut down the ability to do hand gripping to somehow avoid the inevitable hand PEM? Maybe I don’t understand the concept fully…

I too may not well understand their hypothesis, but I do understand your perspective, and agree. Pushing beyond limits, even with knowledge of the possible/likely unpleasant physical outcome (i.e. ‘malaise’), seems to be a common approach of many of us.

Emily and Jane, I agree with your comments. I also sometimes push through, knowing what will happen. I those instances, I don’t usually get a sign to stop. Once I do stop, however, all the negative aspects come rushing in. I’ve always described it as running on adrenaline.

I have seen this in myself as well. I can’t feel the pain until I stop. If I ever stop, I can’t get started again, because I was running on adrenaline for much of the effort.

Why could I do this and why didn’t I feel the pain. If it’s all brain tricks, why does it hurt so bad later?

Janet Dafoe said last week on X/Twitter, “ Ron Davis called up Avi Nath at the beginning and offered to help him and make sure the study included everything and had the right inclusion criteria but he never got called back.” Basically, it’s a flawed and dangerous study/interpretation/invented mechanism which could be used to encourage pushing through symptoms.

Thanks for mentioning this. This story illustrates perfectly what I thought was wrong with that research when I scrolled through the article. They simply don’t take into account all the good work and findings that already exist.

Thanks god there are other studies. I got aware this morning that Prof. Scheibenbogen together with folks from the patient run German Association for ME/CFS published an opinion piece where they have collected all the evidence that has built up by now that shows that ME/CFS is an ordinary somatic illness:

They write:

“Contrary to psychosomatic hypotheses, replicable organic abnormalities are evident in ME/CFS [26]. The most important replicated abnormalities include a significant reduction in cerebral blood flow [27–29], endothelial dysfunction [30,31], a reduction in systemic oxygen supply [32,33], a reduced peak oxygen consumption [34], an increase in ventricular lactate levels [35], hypometabolism [36], and increased levels of autoantibodies against G-protein-coupled receptors [37–39]. Many organic abnormalities found in ME/CFS correlate with symptom severity, indicating a relevant role in the disease process [29,31,37,40]. Moreover, psychological factors did not predict which individuals developed ME/CFS in a prospective study [41].”

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38256344/

I want to repeat: We have replicated knowledge about the foundations of the ME/CFS pathology. We should fight as hell that all researchers who get public funding for their work have actually read up about ME/CFS and Long Covid before they develop a study.

Thank you so much for the excellent information.

There were some interesting findings, but the subject group sounds as if it was an odd selection.

Some useful notations in a summary by journalist Tarun Sai Lomte + additional notes were:

1. A 24-hour ambulatory electrocardiogram (ECG) revealed diminished heart rate variability in PI-ME/CFS subjects.

2. The increased heart rate in PI-ME/CFS subjects throughout the day suggested higher sympathetic activity. Besides, the diminished drop in their nighttime heart rate indicated reduced parasympathetic activity. (Are we not discussing POTS or why it occurs?)

3. Reducing baroslope (decrease the heart rate accordingly to keep blood pressure in the normal range) and prolonged blood pressure recovery following the Valsalva maneuver (bearing down) in PI-ME/CFS suggested reduced baroreflex-cardiovagal function. Overall, data indicated alterations in the autonomic tone. (Causes of autonomic dysfunction can include insulin resistance, abnormal protein build up in organs or amyloidosis, autoimmune nerve damage, the presence of certain pathogens.)

4. Cortisol levels were significantly reduced an hour after the incomplete/flawed(?) CPET in PI-ME/CFS participants, suggesting they were less likely to attain their maximal predicted output

5. PI-ME/CFS subjects showed significantly reduced levels of dihydroxyphenylglycine (DHPG) [*norepinephrine a.k.a noradrenaline is principally converted to the alcohol metabolite DHPG.];

Also low was 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid (DOPAC) which is the main neuronal metabolite of dopamine and low levels of DOPAC in CSfluid characterize Parkinson’s disease even in recently diagnosed patients;

Also low was dihydroxyphenylalanine (DOPA) – a precursor of dopamine which when low can be a neurochemical biomarker of pre-clinical parkinson’s disease in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). These warrant a closer look, no?

It was said they correlate with this purported “effort preference”.

6. Perhaps someone can explain the significance of the subset of aptamers which predicted PI-ME/CFS status by sex and the differences in mitochondrial processes found?

7. Distinct sex signatures of metabolic and immune dysregulation were observed, which suggested persistent antigenic stimulation

We will have to wait for more discussion and clarification of these things by people who understand them, but this paper from such an esteemed group of researchers seems to raise more questions than it answers.

Yes, the catecholamine CSF results were fascinating! 🙂

Well put. I pushed my running after I got sick I ignored all pain and fatigue signals and that permanently made me much worse.

Thanks Cort! Pretty intriguing to get statistically significant OBJECTIVE results AND with such a small sample.

I’m also curious about a few things

– whether the “Effort Preference” part of the test might reflect a biological pathway that inhibits impulses through some cellular level or brain message that inhibits action well before a prethinking level, even though I know many of us have a very strong impulse that we override (and then we overdo). I have felt that inhibition with my own CFS a lot and while I’ve sometimes thought it was my thinking brain (and I have learned to not overdo) it’d be interesting if it might actually reflect an inhibition of that “premovement”at a cellular level in the brain. Not as a thinking inhibition, but as a deep brain driven inhibition of a biological process.

– I’d also wonder whether we might find antibodies in the specific areas of the motor cortex and related areas of the brain, and associated with the functions they looked at that perhaps involve peripheral function (such as the quick weakening in the grip test) … whatever those antibodies might be. I’d think they might find some actual physical structural damage in those whose CFS is worst, and a higher number of antibodies linked to severity as well.

Hi Veronique – it’s been awhile :).

Sample size – agreed – one thing the NIH should take away from this is that even with such a small sample size – and perhaps not the best group either – Nath and team were able to come up with a bunch of findings. Think what the projected study size might have found.

“that inhibits impulses through some cellular level or brain message that inhibits action well before a prethinking level, even though I know many of us have a very strong impulse that we override (and then we overdo).” – I would not be surprised at all about the prethinking part. In fact I would be shocked if it was otherwise.

I thought it was very interesting to see an ACTIVATED motor cortex associated with the weakening group. That suggests there’s a problem somewhere between the motor cortex and the muscles – a nice study project I would think.

Thank you for explaining this. I also felt troubled by the NIH report. Looking forward to Part II.

Thanks for the article cort!

You stated that orthostatic intolerance/POTS did not show up in these patients. This is not correct. Although the paper makes it seem like they did not find OI or POTS. Here is a link to the supplemental paper. Page 48 Shows Dysautonomia was common in PI-ME-CFS. Also Dysautonomia International has confirmed with Dr. Goldstein POTS did show up in some patients.

https://static-content.springer.com/esm/art%3A10.1038%2Fs41467-024-45107-3/MediaObjects/41467_2024_45107_MOESM1_ESM.pdf

I miswrote. They actually stated there wasn’t an increased rate of OI/POTS in the ME/CFS group. Did they find OI/POTS in the healthy controls I wonder?

POTS is becoming increasingly common 4-6 months from Covid infections of any severity, regardless of intervention status. We will see it more and more in populations who were unaware they even had it. Diagnoses are exploding.

I want to be excited by these new findings, but eight million dollars, 75 researchers, a mere 17 ME/CFS participants – who had to be well enough to travel to Baltimore and able to stay for 2 weeks of testing, so is that even a representative group? These factors alone leave me with many questions and a healthy dose of skepticism.

Effort preference? How is that not going to end up seeming like it’s primarily psychological?

ME/CFS patients experience significant fatigue from tasks that aren’t physical – a crossword puzzle can be as fatiguing as a walk around the block. How does this theory explain that?

I always want to be excited and hopeful about new findings, but I’m not sure this study is going to have that effect. I’m going to keep an open mind – if my temporoparietal junction will let me.

Thank you Cort for The Gist – needed even more than usual for this one.

I haven’t read deeply enough into this yet, but I disagree with the authors’ conclusions.

I think that there is a mismatch between effort and expectation of reward because this is our reality. I have no problem with the findings of lower activity in the TPJ. However, I believe that this has physiological causes outside of the brain. This study failed to measure the muscle markers that change during exercise. My reading of this is that they’re putting the cart before the horse. In other words, I believe that muscle failure causes a reduced expectation of reward – not the other way around. I’m concerned about the stigma that this could cause, and that the findings could misdirect future research, funneling research dollars in the wrong direction.

Then there’s the small sample size and the question of whether the participants were typical of the larger ME/CFS population.

Agreed – since ME/CFS researchers often use exercise stressor to plumb the depths of ME/CFS better I’m surprised that we didn’t see more of that. I still have to dig into the exercise section of the paper, though.

What a shame they could not do invasive exercise testing. Not many places have the machines that are able to do that.