It’s the toughest and perhaps most discerning test of all. The two-day maximal exercise test requires that one exercise to exhaustion (or nearly so) two days in a row. In truth, the test is over quickly: it starts out with mild pedaling on a bicycle which slowly gets harder as the resistance is increased and is over in just 8-12 minutes.

It is, however, a maximal exercise test – you exercise to your limit – and that’s why it’s so valuable. It determines how much energy a person – not a cell or a tissue – but an entire person, can pump out.

The remarkable thing is that virtually everyone, whether they’re healthy or sick with any manner of serious diseases, are able to get on a bike, pedal to exhaustion and then pump out the same amount of energy the next day. Whether we’re sick or healthy, somehow our bodies almost always retain the ability to produce energy when needed.

But not apparently in one disease. Chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) appears to be the odd man out. Put some people with ME/CFS on a bike, and their ability to generate energy (e.g. exercise) the next day plummets. That’s an important finding in a disease which introduced the term post-exertional malaise (PEM) to the medical lexicon.

If that finding holds up – and it’s held up in a number of small studies – it would suggest that exercise does things to people with ME/CFS that it doesn’t appear to do to people with other serious diseases.

When we exercise, our bodies use two different systems – anaerobic and aerobic – to produce energy.The aerobic energy production system dominates during exercise to provide a clean and abundant source of energy. When we reach the limits of our aerobic energy production capacity, the anaerobic energy production begins to dominate – but at a cost. Not only does it produce much less energy, but it also produces toxic by-products which, as they build up, produce pain and fatigue.

The VO2 max CPET exercise test has played an important role in ME/CFS because it measures the transition from aerobic to anaerobic energy. Past two-day exercise studies have suggested that many people with ME/CFS exhaust their aerobic energy production systems more quickly than usual. That leaves them dependent on less efficient anaerobic energy production – and suffering from symptoms of pain and fatigue that quickly kick in when that system predominates.

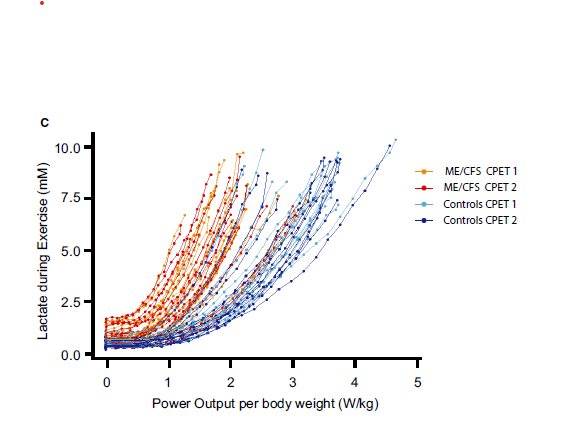

This Norwegian two-day exercise study potentially adds something new to the accumulating evidence that something vital is broken in the energy production systems in ME/CFS: for the first time, lactate accumulations over two exercise tests were assessed.

Lactate – a byproduct of anaerobic energy production – is produced throughout an exercise period, but as the anaerobic energy production system becomes more dominant, lactate accumulations build up. Increased lactate accumulations, then, in ME/CFS, would add another sign that people with ME/CFS are more dependent upon anaerobic energy production than healthy controls.

The Study

Abnormal blood lactate accumulation during repeated exercise testing in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. Katarina Lien1,2 , Bjørn Johansen3, Marit B. Veierød4, Annicke S. Haslestad1, Siv K. Bøhn1, Morten N. Melsom5, Kristin R. Kardel1 & Per O. Iversen1,6. 1 Department of Nutrition, Institute of Basic Medical Sciences, University of Oslo, Oslo, Physiol Rep, 7 (11), 2019, e14138, https://doi.org/10.14814/phy2.14138

As we saw with Rituximab, small countries like Norway can make big waves in ME/CFS if they apply themselves. Now comes another ME/CFS study from Norway, this time led by Katarina Lien.

Lien put 18 women with ME/CFS (who fulfilled the Canadian Consensus Criteria) and 15 healthy females (18–50 years) on the bike for two maximal exercise periods one day apart.

Some Terms

- Tip – Because our cells use oxygen to produce aerobic energy, oxygen consumption is used to assess the amount of energy produced. Therefore, translate “oxygen consumption” into “energy production” when you hear it.

Peak VO2 – Peak VO2 describes the highest rate of oxygen consumption (energy production) that occurs at some point during the exercise test. Because peak VO2 is a one-time measure which can occur at any point during the test, it tells us nothing about the ability to consistently do work, and is not particularly important. Much more important for our concerns is the level of oxygen consumption at GET (Gas Exchange Threshold) or “anaerobic threshold”. (GET in this context does not refer to graded exercise therapy.)

Gas Exchange Threshold (GET) – GET is the point where carbon dioxide levels in the breath rapidly begin to build – indicating that anaerobic energy production has begun to dominate. (It appears to be the same as the anaerobic threshold).

Lactate isn’t the bad actor it was once thought to be – but increased lactate levels do indicate that anaerobic energy production is dominating

Lactate Levels and Lactate Turnpoint – Once the limits of aerobic energy production are reached and anaerobic energy production begins to dominate, increased levels of lactate are produced. Lactate levels can rise very quickly – just two or three minutes of anaerobic energy production are needed to produce high lactate levels. The “lactate turnpoint” is the point at which lactate levels begin to rise very quickly.

Lactate does not cause pain or fatigue. Contrary to what was previously thought, lactate actually helps to retard these symptoms, but high lactate levels are associated with the acidosis responsible for the pain and fatigue when we rely on anaerobic energy production. For our purposes, then, high lactate levels mean increased levels of pain and fatigue.

Absolute Power Output – Absolute power output assesses the amount of power (in watts) produced, adjusted for a person’s size.

Rigor

The authors went to some lengths to ensure their results couldn’t be explained away by deconditioning or some other factor. All the ME/CFS patients had “mild to moderate” ME/CFS (none were bedbound), all had normal hemoglobin concentrations, and all had normal breathing before the exercise test and normal to high “breathing reserve” during the exercise test. Age, gender and height were similar as well. The patients were a bit heavier, but when weight was controlled for, the results did not change.

Healthy controls were deemed ineligible to participate if they were too active (exercised more than once per week). Both the patients and controls had similar mean respiratory exchange ratios and maximum heart rates; i.e. both exerted themselves fully during the test.

Results

Oxygen consumption (VO2) ( i.e. energy production) at the entry into anaerobic energy production (GET) was significantly reduced in the ME/CFS patients compared to healthy controls in both exercise tests. This indicated that ME/CFS patients began having trouble producing energy at a significantly lower exercise level than the healthy controls.

The significantly reduced power output at GET in the ME/CFS patients on both exercise studies indicated the same. It indicated that it took significantly less work for the ME/CFS patients to exhaust the capacity of their aerobic energy production system and begin relying on anaerobic energy production.

Changes from the First Exercise to the Second Exercise Test – the PEM Test

VO2 – Oxygen consumption (energy production)

Despite exercising to exhaustion on the first day, the healthy controls were able to match their energy outputs during the exercise test on the second day. In fact, in some ways they even got stronger.

The ME/CFS patients were not so lucky. Several results suggested that the first exercise session blunted their ability to generate energy. The maximum amount of energy they produced (VO2 peak), and the amount of energy the patients were able to produce before they entered anaerobic energy production (GET), was significantly reduced during the second exercise test.

The second test was particularly important, as a drop in oxygen consumption at GET indicates a quicker entry into anaerobic energy production, fatigue and pain.

Lactate

The healthy controls got stronger during the second exercise test while the ME/CFS patients got weaker.

The lactate results uncovered more significant abnormalities and a sharp divide began to appear. While the healthy controls got stronger on the second exercise test, the ME/CFS patients got weaker.

The lactate levels were similar in both groups at rest, but as soon as the exercise started, things started to go haywire for the ME/CFS patients.

People with ME/CFS had an earlier lactate turnpoint – another sign of earlier entry into anaerobic energy production – during the first and second exercise tests. The fact that ME/CFS patients consistently demonstrated significantly increased lactate levels at any work level (power output) suggested they’d exhibited an increased reliance on anaerobic energy production throughout the test.

The significantly increasing lactate levels the ME/CFS patients produced per power output on the second exercise test indicated they were relying more and more on anaerobic energy production.

Healthy Controls Get Stronger / People with ME/CFS Get Weaker

While ME/CFS patients’ lactate levels at GET significantly increased from the first to the second exercise tests, in the healthy controls lactate levels actually decreased.

Plus, the healthy controls were able to tolerate the lactate that was present better (their lactate levels at the lactate turnpoint increased). They were able to work harder at the second test before their lactate levels began rising rapidly. These findings indicated that the healthy controls’ bodies were rapidly adjusting to and benefitting from the exercise.

The ME/CFS patients, however, showed just the opposite. Their lactate levels began to rise rapidly at significantly lower work levels, their lactate levels at GET increased significantly relative to the healthy controls, and neither their lactate levels at GET, nor their lactate turnpoint improved during the second exercise test.

When assessed for absolute power output, the pattern was the same: more lactate accumulated in the blood of the ME/CFS patients and they entered into anaerobic energy production earlier during the second exercise test.

As the healthy controls produced less lactate and were able to tolerate it better, the ME/CFS patients produced more lactate at lower levels of work. This, in effect, told the tale of how exercise makes an ME/CFS patient weaker while making a healthy person stronger.

Peak VO2

Peak VO2 is the least significant test made as it is a one-time measure of energy consumption.

VO2 at peak exercise (VO2peak) was, however, significantly lower in patients than in controls during the first exercise test and decreased further on the second exercise test.

The authors cited several studies which could provide clues to the exertion problems in ME/CFS including reduced energy production of immune cells, reduced AMPK phosphorylation and glucose uptake in muscle cells, disturbed PDK regulation, elevated LPS levels and exercise induced leaky gut.

Conclusion

The authors’ conclusion was as devastating as it was simple:

“exercise deteriorates physical performance and increases lactate during exercise in patients with ME/CFS while it lowers in healthy subjects”. Lien et al.

Numerous data points indicated that instead of making people with ME/CFS stronger, a maximal exercise test one day impaired their ability to generate energy the next day. While lactate accumulations were not significantly increased in the ME/CFS patients during the second exercise test they were significantly increased throughout the tests when power output was taken into account. The earlier lactate turnpoint also suggested ME/CFS patients enter into anaerobic functioning earlier during exercise as did decreased oxygen consumption at anaerobic threshold (or GET).

Workwell’s 2-day exercise tests suggest people with ME/CFS may demonstrate a unique inability to exercise,

The lactate accumulations add an important data point. Past ME/CFS lactate studies have had mixed results, but none had applied the crucial element – the second day exercise test regimen that Workwell introduced into the field so many years ago. Now we have another data point which indicates the havoc that exercise – in this case a short but intense bout of exercise – wreaks on ME/CFS patients’ ability to produce energy.

ME/CFS, in effect, got lucky when a small team of exercise physiologists at the University of the Pacific in Stockton, California introduced a vital element to this field: the two-day exercise test. Adding that second day uncovered a possibly unique feature of ME/CFS (inability to reproduce energy the second day), biologically validated the existence of post-exertional malaise (PEM), demolished the idea that deconditioning is responsible for the exertion intolerance in ME/CFS, and provided an objective test that has proved crucial in disability cases.

- Exercise is a hot topic right now. Blogs on several more exercise studies are coming up, plus Workwell begins its Medbridge educational program for rehabilitation professionals treating people with ME/CFS.

Endocrinologist Dr. Gunnar Aasen in Oslo was doing a simple exercise cycle test since the early 2000’s? I was there in 2008. They hook up EKG leads to your chest and he tells you to cycle until you feel the lactic acid in your legs. He can tell quickly if you’re just deconditioned or if you’ve got CFS/ME. It wouldn’t surprise me if his testing method influenced their research.

https://www.dagbladet.no/tema/lege-ga-for-mange-me-diagnoser-mistet-retten-til-a-skrive-sykemeldinger/70808296

Physician gave too many ME diagnoses: (loosely translated)

March 16, 2019: In April last year, a doctor in Oslo lost the right to write patient declarations valid for Labour and Welfare Service (NAV). That is, he is no longer allowed to write sick leave and other statements, such as medical statements about disability. The decision applies to all types of declarations to NAV.

NAV examined a random sample of 40 patients who had been diagnosed with ME by the physician in the period 2013-2017.

The private practitioner is a specialist in internal medicine and endocrinology. He strongly disagrees with the NAV’s decision.

– The decision primarily affects ME patients and is an attempt to hamper applications for social security benefits for a group of patients who are already disadvantaged. These are social security benefits they are entitled to, benefits they do not receive because NAV has major problems accepting the diagnosis. In reality, NAV now blocked for the ability to screen for an ME diagnosis by a specialist, because the waiting time is so long, the doctor says to Dagbladet.

-> not many ME/CFS specialist/expert left in Norway, and this is one way to make them disappear….

Marit, that’s horrible. He is an insightful endocrinologist, and a person who truly cares. Thanks for the summary, I can’t access the article. Lykke til, Dr. Aasen.

You could show that ME/CFS patients literally dropped dead after the second day of exercise, and mainstream physicians would still scoff and ignore the results. We need studies that provide treatments and solutions, not that validate what we with ME already know and the mainstream idiots will never accept!

Doctors seem to be the last to get it unfortunately! These studies are vitally important, though, because they provide biological proof of the mysterious exercise intolerance seen in ME/CFS. The fact that exercise intolerance is so rare outside ME/CFS is one reason doctors don’t get it. Hopefully as these kinds of studies keep coming they’ll start getting the message.

These studies also highlight how crucial it is that researchers understand what is going on with energy production in ME/CFS.

We could really use some large exercise studies…

Of course, effective treatments are the greatest revenge!

Thanks Cort for reaffirming the truth about most doctor’s unawareness. It’s hard to explain to friends and workmates that you can’t work out to aerobic condition, without crashing the next two days, and even harder to explain to the medical profession! This study, and hopefully future ones will prove this condition has a more physical/neurological connection, than a psychological one. Netflix’s “AFFLICTED” series seems to end with the notion that many of these undiagnosed illnesses might be more mentally triggered, than environmentally or biologically induced, which appears to me yet another “tunnel-vision” analysis of the problem.

Agree with many of these comments! These studies are wonderful and so needed,but the mainstream physicians never see this data, and pretty much ignore the patient anyway. Until MASS education of this disease and how devastating it is, most primary doctors will never try or want to treat the patient. Plus unless they have tons of knowledge about it, they wouldn’t provide the treatment (drug) even is there was one.

It’s not so much about proving the disability to individual doctors, though that is important — it’s about understanding the actual causes of the symptoms we experience, so we CAN figure out what is behind them. And it’s also about helping people get positive diagnostic evidence, instead of the ‘diagnosis by process of elimination’ that is so common in most of the world, and which interferes with getting any sort of disability aid.

“Literally drop dead”?? That means actual death. No, we FEEL like we’re dying, but we’re not actually dying.

Hi Susan,

People have very individual experiences with this condition.

I’m sometimes surprised I am still alive.

I have done this two day test too. Because at the time my ME was mild on day one my energy output was good. But two days later the output was below very poor.

What happened subsequently was that I went slowly down hill until I was housebound. I wondered whether the exercise test caused a relapse which I haven’t fully recovered from over two years later.

I would be interested in knowing whether any other people in this study had the same experience?

Workwell has analyzed patient responses to the 2-day exercise test and found that most people do recover over time; i.e. within a couple of days to a couple of months but a few people do report long term effects. In cases like yours where your decline is gradual it’s hard to know what is causing what. The exercise clearly really stressed your system, though, for your energy output to decline like that. it’s not unusual on the other hand for patients to test out OK on the first test and quite poorly on the second.

Thanks very much Cort. Young comment makes a lot of sense.

There are some comments about inflammation below. My CPR and from memory ESR are fine but Ferritin is higher when worse. Usually when worse is around 900 and about 700 when better. No one has been able to tell me why yet. I haven’t got hemecromotosis. Have recently found Copper is below bottom of the range and I’m struggling to get it up. I think I do absorb some but maybe I’m using it with fighting the inflammation with SOD. I’d be very interested in any comments. Thanks again. Steve

PS young should read your.

Steve, I would be interested to know too. This is the horrible, ironic, dark side to any exercise testing. In order to prove themselves, some people have to risk getting a relapse, recurring illness, new illness, and/or lower quality of life.

Where I live it resembles a bit that with suspected ME/CFS/FM you get the “standard” CBT/GET “treatment”. You can say no, but that proves you are not willing to do an effort.

In order to be eligible for disability income, you must prove you are willing to do an effort. And I was unable to gain my own income anymore so I really needed that income. I’m all for that to shake off freeloaders. But not if this “proof” is by doing the very very badly flawed CBT/GET poison thing.

I am one of many that “proved” my ME/CFS/FM was real by crashing very hard. In my case I got from being relatively independent to need a wheelchair and be unable to speak in sentences within months thanks to this “piece of benign therapy”. Life became hell on earth within months after starting it.

It took me four years of heroic effort to shake of the worst of it and still not get to the point where I was before this disaster.

This is why repeat CPET is primarily a research tool unless people need it for legal or bureaucratic purposes. The development of the nanoneedle test, while probably not specific, is far safer and shows a similar issue. Under energetic stress to cells our cells cannot handle the energy demand. I suspect that some version of cell testing, from a blood test, is going to be more clinically useful than CPET in the long run, but CPET is invaluable to research for the foreseeable future.

Thanks Debs. Yes, isn’t this the case in the US? That’s so unjust. It’s hard enough to live with this as it is. Mine was for a University study. Might have helped someone get their masters, but at a cost. I doubt anything new came from it. All the best.

Yes I’ve heard researchers saying this test is unethical because it permanently worsens ME/CFS in some people. I’ve read this several times now of patients never recovering.

I was meant to do the 2 day exercise test at Massy University but my brain fog luckily made me forget to go. Plus I think I was actually too severe at the time. And the researchers said not to come. I’m so glad that happened.

Sorry to hear it affected you do badly though

Thanks. You were lucky. There is no way I’m going to do that again. 2 years later and I’m only now starting to slowly come back.

I ran to my limits for a cardiac test. About 20 Minutes. The following month was my worst in terms of pain. At the times I did not know anything about the disease nor the pacing. It took me about 6 months to start pacing and avoid getting over 95 heart beats per minute, the threshold I figured I shouldn’t exceed. I now considered I have a mild ME, only because of pacing and accepting a very different life.

I did the 2 day CPET as part of a study at Cornell-weill earlier this year. They were very surprised by my lactate levels on day 2. Had not seen such a dramatic rise before (I was one of the earliest participants and most severe at that point) and the overseeing nurse actually questioned if the test had been done correctly.

Will be very interesting to see the full results when the study is done!

I did a 2-day CPET test in January 2019. The day after the second CPET, I descended into a state of severe exhaustion and body-wide inflammation from which I have still not recovered. I can’t over-emphasize how devastating the aftereffects of these tests have been: the worst 7 months of my life by far. I was already quite severely ill with CFS, but could do a little part-time sedentary work, but I have been housebound and not far off bed-bound since January. I still don’t know if I will ever recover.

I am skeptical of the conclusions people are drawing about PEM during the second CPET tests. Having lived with CFS (I like the name SEID myself) for 35 years, I know very well what PEM feels like, and I can tell you that during the second CPET I was NOT feeling any PEM at all. I did notice that my legs felt more achy than on the first CPET, presumably due to more lactic acid, but that is not the same as PEM, which seems to pervades one’s brain and whole body. So there was no warning of the calamity to come; I even drove the 90 miles home on the day of the second test without any problems.

One other observation: I had done a one-off CPET about 8 months before the double one with no subsequent PEM, to my great surprise. This again tells me that I was not experiencing PEM on the day of January’s second CPET. I was certainly more severely ill than someone with moderate CFS, so I would not expect the patient volunteers who have moderate CFS to be in PEM on the second CPET. To me, this is a flaw in the experiment, however, the biggest flaw is that it makes some of us extremely ill!

Robert, your description “no warning of the calamity to come” is so good. This happens to me. You think you’ve got it all figured out, living with this crap for decades, and for some reason you overexert – but there is no PEM! Not even the “day after the day”. And then you think “there is nothing wrong with me anymore! This crap is over!” And then WHAM! It hits an extra day or two later and down for the duration. I wonder if this becase we are at a later stage?

I agree, the 2nd day exercise test does not begin to touch the depth of PEM I get, for example, the day after simply going to worship services & out to eat afterward. It is obviously picking up on something that will hopefully prove to be helpful but it still is not capturing full blown-hit-by-a-truck- PEM, didn’t in my case.

Yes, Steve, I had my CPET about a year ago. Housebound within a week (I am stubborn, and resisted the PEM), devolving into a year/long relapse with physical capacity at 10%. Now I’ve climbed to 20%, but am scared to try any “conditioning” exercises.

Thanks Rob. That’s tough. Have you tried heart rate monitoring as an indication of how you are? I’ve found I don’t increase walking much at all until I can sit for long periods without the heart rate rising by very much. Feeling my pulse manually I’ve found is more reliable than watches. Good luck.

Any physical, chemical, or emotional stressor (including a woman’s monthly cycle) lowers the immune system and can make CFS worse.

Since a stressed/unwell body burns more nutrients and anti-oxidants (esp. Vit C and B -vites) than a healthy body, a very nutritious ‘clean’ low-fat diet and supplementation is quite necessary for rebuilding the immune system and recovery.

The late virologist Dr Martin Lerner’s supplement protocol is: as much Magnesium as tolerated, & spread over the day; CoQ10 (ubiquinol form), Niacin (B3), & ALA is start, along with a high quality multi Vit/Min (with all natural forms of vitamins and several of each), but replace most of the L-Carnitine with L-lysine, add some folate (precursor folic acid doesn’t count) and the adenosylcobalamin form of B-12, taken sublingually.

Then consume every fruit, wild berry, herb, and tea deemed an ‘anti-oxidant’ and/or ‘anti-viral’ in TCM or Ayurvedic medicine (Lemon Balm, Nettle, Chaga, etc.) at least 3x/day. And since some taste not-so-great, mixing with others you like is fine.

At least try it for a month and see if it helps.

When looking at the paper https://physoc.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.14814/phy2.14138 I see another point of interest, figures 2c and 2d:

* Peak heart rate clearly increased on the second day with patients and decreased with healthy controls; Peak heart rate was lower with patients then with controls too.

* Less clear: Peak respiratory exchange rate increased with patients on the second day but (insignificantly) dropped with healthy controls.

=> That resembles my fatal CBT/GET (Graded Exercise Training here). After a month of this very destructive program my heart rate was near locked between 90 BPM (resting) and 95 BPM (exercising till I dropped from the treadmill) and breathing got constantly faster too.

Well, fatal as putting me in a wheelchair and making my life a hell on earth rather then actual dying.

Interesting….Peak heart rate increased in the ME/CFS patients – apparently in an attempt to shove more blood into their tissues/get more oxygen to their muscles while it declined in the healthy controls -as they presumably improved their oxygen delivery to their muscles!

Another fascinating demonstration of impaired energy consumption because of exercise.

I bet it was an increase in hart rate, not volume of blood pumped per minute. In that case it would indicate increased problems with hart prefill rate the second day.

If so, that might IMO be do to too much inflammation and inflammatory debris clogging the capillaries.

The difference in peak heart rate was trivial. Compared to the other 5 studies that reported peak heart rate, there is no clear pattern.

https://www.me-pedia.org/wiki/Two-day_cardiopulmonary_exercise_test

I’d argue there is a bias towards slightly lower peak heart rates on the second day, simply because it is even harder to reach peak exertion on the second day. When participants have a significantly higher heart rate on the second day, I suspect they didn’t reach a true peak exertion on the first day. This is why the trend in VO2Peak results between studies seem to be inconsistent. Compared to the results at the ventilatory threshold, which don’t depend on motivation, seem to be consistently demonstrating poorer performance for CFS patients on the second day.

A ‘locked’ heart rate is strange. Shows a neurological issue with the vagus nerve, and a vit/min deficiency.

Did your doctor ever measure your Heart Rate Variabily? Or test for electrolytes potassium, sodium, chloride, iodide, magnesium, selenium and CoQ10 levels? They should all be optimized. Just like how your your car will barely start with a battery running low on acids, your heart is the same. Ejection factor might be off a tiny little bit, but with CFS, usually nothing shows up in most normal cardiology tests, and the heart’s electrical system (EKG) is otherwise fine.

Need to figure out what your body is trying to tell you and address all possible causes of your body or heart doing some weird adaptation before you take a med or add a device to mask the symptoms instead of reverse and cure them.

HRV can actually be tested every morning at home with a $40 bluetooth heart rate chest strap and a free App. If normalized to a 0-100 scale: 0 =dead, 100= rested athlete. Most people are in the 60-80 range, then 40-60 the morning after exercise (such as bicycling 40+ miles), then back to 60-80 the next day. Consistant readings <40 imply the Vagus nerve has a viral infection.

A study found that the people with a consistantly low HRV would have a heart attack in the next 3 years (if they havent already just had one, which is usually what triggers a Cardiologist to do a Holter HRV test), and the average life expectancy is 58 (controls =83). I was 57 when I read the report, and I had a low average HRV of around 42 (36-50), so it scared me. I was a CFS level "3" at the time, and my heart would race to 183-189 bpm and gasping for more more oxygen when bicycling up a gentle 4%‐6% grade that my other retiree riding companions, all in their late 60s and 70s, could do with relative ease. After 2 years of bicycling 2x/wk, not much changed besides my HR dropping back to normal quicker afterwards (1 min. vs. 20 min.), and me trying to avoid all hills.

Susan, if you’re the ex-power lifter from the other comment, I’d like to trade notes with you. Contact:

electron.effigy at google mail.

I used to get PEM approximately 30 hours after exercise and I’d be interested to see what the results would be if a test was done with a 48 hour gap to the second test.

Or better yet a 3-day test. It would probably be too brutal for patients, but I imagine the drop off in performance from day 2 to day 3 would be much more dramatic than from day 1 to day 2. Actually now I’ve written that, I wouldn’t want any PWME to go through such a test as I expect the recovery period would be weeks to years long. That said, my mind boggles at the data that could be uncovered.

Yes it does! I’ve always thought that the most effective study would be to have patients exercise and then measure everything and then do it again (and if they were strong enough do it again.) In the past I’m sure I could have handled it. I don’t know right now.

I’m sure they’ll stick with the two-day exercise test but I agree that separating exercise tests by a couple more days and then hitting patients at the peak of the PEM would be fascinating.

I get scared just thinking of the potential impact of this type of test – reading some of the experiences in these comments is enough to put me off ever doing it. I have an insurance claim pending so a CPET could be useful for the evidence cache.

It has got to be one of the worst catch-22 situations for us, if the testing could be done and the data captured to either prove/disprove certain differences between patients and HCs, without putting the patient health at risk, this surely would be a highly beneficial means of investigating and potentially quantifying the level of disability for the condition and individual patients. Or what if a pre-test marker (blood sample) could be found which reliably predicts reduction of physical capacity on day 2, then that would be even better. I guess there are a lot of ideas being kicked around out there…

I agree, a two day study-test is very limited, but I’m glad there are scientist giving it a go to trie to understand. PEM is real. It’s the most confounding part of this illness.

Agreed! For me it’s always been the one symptom that stands out – if I over exert myself, particularly physically, there’s hell to pay! That’s very unusual! I think the fact that the term PEM was coined for ME/CFS and hasn’t shown up in all these other diseases after so many years really means something.

It’s not an easy decision for sure. Workwell’s post-test assessments of patients doing the test indicate, if I remember correctly, that most recover within a week, a significant number take longer and the vast majority ultimately recover back to baseline. A few unfortunately apparently do not. Workwell assesses, as best they can, the ability of each person to take the test and will not test severely ill patients.

As for the 2 day test:

It seems that the issue is a test for people who worked a normal job (thus a 5+ CFS Energy Index Point Score) getting disabilty when they get worse and can not work.

They just need to grade CFS people on the 0-10 CFS Energy Point Index, Throw out the 0, 1,2’s and 8, 9,10s, and test them every day for 4 days.

They also need to compare long term CFSP to short term, ex-top athletes to non athletes, men to women, and diets low carb/Paleo vs low fat/Vegetarian, std diet vs organic, to see how different subgroups make a difference. That may get us closer to an answer if one subgroup does noticeably better than another.

As an ex-athlete who watched my weight and diet since age 14, I am curious as to how athletic background changes results, since a champion runner would have a greatly different physiology as a champion powerlifter (like me), who is used to an exercise ‘set’ lasting <20 seconds and has developed totally different anaerobic energy pathways and muscle fibers.

I notice when bicycling, I never feel the 'burn' of lactate buildup (bicycling is super easy compared to the 315 lb squats that I use to train with!). I found it makes no difference if I eat or not during a 2 hour flat ride, and I do not burn fat/lose weight from cycling (as I had hoped), despite a 1350 cal/day low carb normal diet, with a 400 cal snack (Starbucks!) during a 2‐2.5 hour flat easy (12 mph avg) ride.

Instead my hair and nails get very thin and damaged (which showed up months after becoming a '3' or '4' for awhile & bumping my miles up to 35-40), implying my body is using protein instead of fat as an energy source after stored glycogen is semi-depleted. The pushing of myself to do a little more for a month or so also knocked me down to a 1 for a year, with occasional '2' days.

Cort:

If you know of a study showing energy source in (mildish untortured) CFS people AFTER their liver is semi-depleted of carbs, I would love to see if it matches what I found.

…And if there is any known fix-it to force, ooops, 'encourage', the CFS person's body to use fat+oxygen as fuel.

Also am curious as to what might help oxygen getting from the blood and into the cells in CFS-P besides possibly (Rx)Anavar or (to a much lesser degree) Cordyceps Mushrooms, which have been shown to help Normals. If any readers have found something as to results of the above or similar in CFS people, please reply.

I agree wholeheartedly Manshadow. Often after over-exerting, I am not too bad the following day, but then on days 2 and 3 I am barely able to function. Surely this must be a defining finding between PWME and healthy controls that could not possibly be refuted.

My low point hits on day 3. I go down after exertion, but it continues down till day 3. Like clockwork. Not sure why it takes 3 days to hit the low. Seems like an immune response maybe.

Interesting that dichloroacetate is used as a treatment for some forms of lactic acidosis, see e.g. :https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S109671921300108X

Dichloroacetate has also been trialled for me/cfs due to its effect on the pyruvate pathway https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29602463

Hmmm… Wonder if a Casper might be helpful here? My neurologist recently got one, and I was able to try it – this explains what it does and the benefits:

https://decodingsuperhuman.com/vasper/

Wonder if using it would change 2 day CPET results or improve our function with regular use?

It’s essential that researchers are very careful not to jeopardize the health of PWME by doing exercise intolerance tests, interesting though they are. Listen to us. We know we get PEM. In a moment of madness I hit some golf balls two and a half years ago, having had mild/moderate ME for 12 years. I was feeling better than I had done for ages and was very keen to pick up my childhood hobby and join my husband on the golf course. Big mistake.

I experienced delayed PEM and, about three days after hitting the balls, plunged into a relapse. I could funtion for between only 2-4 hours per day for about three months. I have improved very gradually but still have much less tolerance to exercise than I had before hitting those wretched golf balls.

I am lucky in that I have regained some quality of life and can feel energised at times. The problem with this is that I then end up doing too much, e.g. too much pruning or weeding in the garden. I never dig or carry anything heavy now as I know this will result in having to lie down for the rest of the day.

I’m happy to work with any researcher who would like to follow me for a typical day and take blood samples at energised and PEM times. I would refuse to exert myself to my limit in a test centre.

“It’s essential that researchers are very careful not to jeopardize the health of PWME by doing exercise intolerance tests, interesting though they are.”

There are some people for whom the test and studies like this are appropriate and those for whom it’s not. You’ve self-selected yourself out and it sounds like you made the right choice but it’s not true that these tests or tests like them are damaging the health of everyone or even most people or even a significant subset of people who take them. Studies commonly employ an exercise or other stressor in ME/CFS – dozens have probably been done – and they’ve have been crucial in increasing our understanding of ME/CFS. We know that tests taken during rest don’t show nearly as much as tests which use a stressor

If exercise tests are taken off the table we lose a vital way to uncover the biological processes taking place in this disease.

“Listen to us. We know we get PEM.”

I can’t overemphasize how little impact a person saying they have PEM has on the scientific community. These studies are not done to prove to patients that they have PEM: they’re done to prove to the scientific community that something called PEM is present and needs to be researched. It is, after all, the core symptom of this disease. In order to explicate it has to be manifested; i.e. a stressor has to be applied.

Those people who are too weak to handle a stressor like exercise shouldn’t participate which is fine because there are many other people who can. Hopefully at some point researchers won’t have to whack patients so hard in order to get answers. Several researchers – Alain Moreau – is one is working on alternative stressors to use in studies.

Great study. We all know PEM is a big part of cfs, so it’s good to have rigorous studies that prove it.

The next big thing is WHY????

Surely it’s coming back to inflammation.

🙂 yes…..WHY????? That is the question. (you sound like me.)

Inflammation and Autoimmune issues, core

I have mild cfs but I am having one of my flare ups. When these happen I typically get a stiff and slightly sore lower back, I get some gut symptoms, my walking tolerance lessens, and my mental fatigue and depression worsens.

I am 100% sure all these symptoms are related, and the only thing I think is common to all must be inflammation?

There was a cyclist who biked the tour de France, I think on the Norwegian women’s team? Ingeborg something iirc. She got sick, was interviewed about her illness for radio and a Norwegian blog transcribed it. She improved greatly thru extreme pacing based on lactate readings.

I wish I could find the blog again, it’s an ME blog. She joked that it should be called tour de France disease because the lactate readings she got we beyond what she’d had as an elite athlete.

Whoa….I had not heard of her. Check out this blog on a doctor who apparently became a lactate super-responder. Not everyone, by the way, has increased lactate levels – at least on the first exercise test.

https://www.healthrising.org/blog/2015/09/25/walking-marathon-me-cfs-case-study/

About the norwegian cyclist you mentioned , Ingunn Ullerhaug, «The top athlete who got ME». Ullerhaug gave an good and long interview on the radio. SERENDIPITYCAT who by the way has done so much for the ME community here in Norway has done an amazing job of making this radio interview available as text. It’s in norwegian, but you may use google translate.

http://www.serendipitycat.no/2019/06/06/transkripsjon-av-nrk-p2-ekko-om-me-forskning-06-06-2019/

Kristin, takk! The part about EPO and thick blood is new and interesting. I hope the researchers taking good notes. And I like the end where she jokes about getting help from (doping) doctors who know best how to remove lactic acid. (For those confused by the Google Translate, you’ll see “baptism” but the word is “dope”, haha )

Thank you! I’d been trying to find that blog again but my brain fog can’t handle multi lingual googling!

Lactic acid can also be caused by dysfunction of Mitrochondria Complex.

And, many of us have found APS and issues with clotting factors and too thick blood. So that does Factor in.

Lactic Acid issues are also in Glycogen Storage Disease (GSD) so is exercise intolerance…Any More News yet Cort on when the GSD Genetic Team will come out with their work & links to ME/CFS?

Nothing yet!

I was so weak I could not do a basic treadmill test.

When Professor Shungu finds excess lactate in the brains of ME/CFS patients, is it just there because blood from muscles circulates through the brain, or is it there because the brain cells also are functioning beyond anaerobic threshold?

I believe Shungu’s thesis is that the brain is often relying on anaerobic functioning

Shungu seems to think lack of blood flow in the brain is causing the problem, not mitochondrial dysfunction. He says, “In addition to measuring lactate, we also measured brain blood flow in patients with ME/CFS and found, in agreement with others, extensive regional and global decreases in blood flow. We therefore speculated that our finding of lactate elevations in ME/CFS was likely related to decreased cerebral blood flow and attendant increase in anaerobic glycolysis, which increases lactate production. Mitochondrial dysfunction is another possibility that we are currently investigating by assessing cell energetics before and after symptom provocation with exercise.”

As I have commented here, I am currently doing Stanford’s Abilify micro dose treatment and have noticed about a 15-20% improvement in my energy. Before PEM would hit about the 2nd day, now interestingly enough, I can go for perhaps 2 to 4 days at a moderate (for me) pace without falling prey to PEM.

I did that just recently as my contractor didn’t show up and left me spending 3 or 4 hours each day trying to finish painting my deck. Well that lasted about 4 days and now I am in a crash.

I don’t know how these Norwegian results may explain PEMs related to

non-exercise stressors. Before, when I have had events like stressful phone conversations or perhaps I would watch a ‘thriller’ movie which caused emotional distress, I would most definitely suffer from PEM the following day. What about those?

About the only think I can think of that exercise and non-exercise stressors have in common is heart rate. Maybe that has something to do with it? Well, then there is a flood of hormones and such? Who knows?

Just throwing some ideas around…

hey nancy!

what dose of abilify are you taking if I may ask, and also how much did you benefit over all from it? Did you take AD before (longtime?)? ty!

Hey Christoph!

I take 1 capsule of compounded .25mg. each morning of Abilify. Stanford’s theory for using it is to tamp down neuroinflammation.

As I mentioned before, the next step Stanford wants to do is add Plaquinil–and not at a tiny dose. I don’t know if I will agree to that as I already have a worrisome retina thanks to my EDS (Ehlers-Danlos).

I also use Modafinil as an adjunct medication. Unfortunately, it will not work if I am way out of bounds in my energy envelope, but normally it does help.

Also thought I’d add that about once a month or so, I will have an almost normal (very abnormal for me) day of ‘super’ energy. I don’t know why this happens but just note it as a welcomed anomaly. I wish I could figure it out so I could replicate it more often.

Hey Nancy,

thank you for your reply.

I am a (very) severe patient for 2 years now, completely bedridden.

I am not a big fan of such medication but will have to try something else at some point.

May I ask you how severe you are/were?

Do you think we could get in contact to exchange information?

Thank you.

Hi Back Christoph!

At my worst, I wasn’t completely bedridden, but I was housebound. I could hardly walk and had a set of other symptoms as well; dizziness, swollen lymph nodes, low grade fevers, and a feeling of extreme leg weakness as well as overwhelming fatigue. This lasted for months and months, and finally began to abate at about the 14th month, although the fatigue remained.

It all came about after I caught a ‘head cold’ while on a trek in the Himalayas. Several weeks after the trek I passed out on the street and that is where the trouble, and the ME/CFS began. Currently I operate at about a 40 on a scale of 1-100, which is a bit less than half my previous energy. It has slowly improved since that trek, but the original onset was over 20 years ago. I also have Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome which adds more to the mix and as I age, things get worse anyway.

I have put in a request that we all can have a chance to compare our coping/treatment strategies and Cort has hinted that it is coming in the future. I sure hope so. Meanwhile you can find a lot of information by combing though Health Rising’s ‘stacks’ of older articles, that is, if you have the brain power while in bed. Poco a poco.

I’m fine if you want to give me your e-mail and I will contact you. I’m very sorry that you are bed bound. I’m not sure how much help I can give except to exchange encouragement, and perhaps reports of my many self-experiments. Here’s to wishing you well…

I suspect lactic acid high enough for you to feel a burn is very rare, even in us. The real culprit is carbonic acid. This was discussed by people at Workwell, but its an old finding. Lactic acid is good in the short term, as its one mechanism to increase oxygen dumping to the tissues, though increased carbonic acid is still more important there.

Exercise testing goes back to the 80s at least. Repeat testing in a formal fashion only goes back to 2007.

We already knew, by inference, that lactic acid would increase in us. This confirms it.

I think that we have a core tendency to the conditions that lead to lactic acidosis, but our low oxygen demand, due to decreased emphasis on aerobic metabolism, means we are more resistant.

I think it was UK research that showed we have high lactic acid after exercise, but low at rest, leading to an alkaline pH most of the time. This would confer additional resistance to lactic acidosis. Lactic acid needs to be elevated for days for it to induce lactic acidosis, due to induced changes in enzyme synthesis.

The results surely come as no surprise to those of us with CFS. I was a keen athlete when I contracted it and I always thought that my fitness prior to it was why I was not as badly affected as many. For example I was used to coping with high levels of Lactic in the blood, and used to clearing it out.

I am now recovered to the extent that I am able to hike and bike ride for 6-7 hours and run (well jog) for 1 hours. But I am very careful not to go out of my aerobic zone, if I go anaerobic I will pay for it later (sometimes for days afterwards). I certainly wouldn’t attempt a test to exhaustion!

All my recover has been down to my own efforts, doctors have been useless. Being used to training using heart rate, I remember explaining to a doctor that my resting HR was now 40% higher than it used to be, and being told it was OK ‘it was in the normal range’. The fact that when I walked upstairs my HR went to the sort of values I used I get when sprinting, I was told could be just because I had become unfit in the couple of months (up to that point) that I had been unable to train!

Hi Ian,

How would you clear the lactic from your blood?

https://www.verywellfit.com/how-baking-soda-can-improve-athletic-performance-4057192

Baking soda

Use with caution, can have bad consequences if not used correctly.

Tracy Anne

Lactate is recycled by the body, once the exercise intensity is reduced. It is another process that is developed through athletic training, in the same way as strength, VO2max, stroke volume in the heart etc. are all better developed in a trained athlete than in an unfit individual. I was not talking about any external substances, but the effects of years of athletic training.

Thanks Ian for your reply below.

The reason I asked is because I wondered whether my Clogged Exhaust Brain is caused by a build up of lactate.

I don’t have muscle pain, I have brain issues – Vertigo Brain, Smouldering Brain, Drooping Heavy Brain, Alzheimer’s Brain etc and at present Functioning Enough Brain ☺️

I have extensive food intolerances and they contribute to most of my issues.

But Clogged Exhaust Brain occurs, in particular, when I have done too much talking to another person. I think it must use a tremendous amount of energy to interact in this way.

I know I have difficulty getting energy to my brain – I don’t know about the oxygen. So I think my brain is running into trouble and then too much lactate is building up. I just feel like my brain is seizing up – it still functions but very, very slowly.

I also get dehydrated but I’m never really thirsty. This showed up on a blood test where my kidney result (creatinine?) went up to about 105, from normally being 50/60. It went down again when I focussed on issues that caused the dehydration – fructose makes me pee a lot.

I seem to be helped by regularly drinking water, which seems obvious but I wonder whether my brain is using more fluid than ‘normal’.

I’ve never been a super fit athlete but I’ve always been very active. I’m 58 and so fit into the middle aged category ?

So, that means that though I have had all sorts of issues – I am within the ‘norm’ or better than my contemporaries.

Over the last few years I have been fighting to stop myself permanently slipping down into becoming a ‘sick’ middle aged person.

I’ve had to work things out myself and am actually doing very well now.

I’m intrigued by Jarred Younger’s brain inflammation ideas and fit in with the comments made after the piece on him from last year.

I like his no-nonsense approach to brain inflammation. Most people can’t get a grip on the notion of an inflamed brain. I have asthma now (inflamed lungs), Interstitial Cystitis (bladder), Eyes, Bowel etc etc Why not the brain?

I’ve calmed most things down, now it’s time to Tame my Brain!

Hi Issie,

Thanks for your thoughts. I read the article and it was very interesting.

However I have been trying out Baking Soda over the last month or so, in relation to Interstitial Cystitis. Some food sets that off but when I took the Bicarbonate of Soda I felt very unwell. I repeated this, not knowing what instigated the first upset!

I then thought I’d drink Mineral water, which has bicarbonate in it and other salts. However I am wondering whether my liver just can’t process the salt? I feel peculiar and my heart rhythm seems to be all over the place.

I also have heart rhythm problems with medications like Ibuprofen and Paracetamol. I took two Paracetamol on separate days and they set off my heart rhythm and asthma – not good.

Actually I also managed to kick a wasps nest and a small squadron immediately took flight and began stinging me!

I’ve never been stung before and wondered what would happen next? Anyway used apple cider vinegar and obviously survived ?

I did also think maybe like the Viper venom was it? – this incident may sort all my problems ?

No it didn’t and I had to get some very cross wasps out of my clothes. I left my boots outside all night and they were full of water as it rained and one wasp stowed away in one of my coats and then crawled under my clothes and stung me again!

Tracey, soda can affect the heart. One reason I wrote to be cautious as it can have some bad consequences.

Issie

Hi Ian,

The way Workwell Foundation (discovered the 2-day CPET objectively demonstrates PEM) explains it, the *aerobic* system is “broken” in ME patients. And so, our bodies compensate for that by using the anaerobic system instead (with the terrible cost that entails). This is why Workwell recommends a *safe* ANAEROBIC exercise program (the final phase of the program ventures into aerobic territory but very, very controlled & few ME patients reach it).

The use of the term ‘anaerobic’ can at first seem counterintuitive …

After rest, everyone (healthy and ME) uses anaerobic metabolism for up to 2 minutes, which is when non-ME people switch over to aerobic metabolism (but people with ME can’t). This little window is what Workwell’s safe anaerobic exercise program utilizes (except the final phase).

The anaerobic threshold (AT) which occurs AFTER exertion — is a different anaerobic (anaerobic is “without oxygen” in both cases but the anaerobic phases ocur at different times relative to exercise and rest). People with ME switch over to anaerobic way too early.

And the kicker is there is only *one* way to know your heart rate at anaerobic threshold — the heart rate at which you stay below as a person with ME – a CPET (actually it has to be a 2-day CPET because on Day 2, the HR at AT can drop for us). The standard calculations available are just a generalized estimate.

So, the bottom line is that conditioning our anaerobic systems is the safe way for us to exercise (it doesn’t look anything like an exercise program for most of us pre-illness).

Workwell has an excellent new video that describes what happened to an ME patient who developed their own program and walked (aerobic exercise) regularly — they had 2-day CPET’s before and after their walking exercise program). It didn’t work out and their CPET results plunged. It’s a cautionary tale for us:

https://workwellfoundation.org/research-latest-news/ “Understanding Graded Exercise Therapy, Part 1” (they discuss why the PACE trial conclusions are so harmful for people with ME). The segment which may be of interest to you begins at the 4:48 minute mark:

If this is as clear as mud, check out Workwell’s website instead to get a good explanation 🙂

Waiting

Thank you for the link, I will look through it all.

However it sounds the wrong way round. I can agree that ME/CFS sufferers have a damaged Aerobic system and therefore tap in to Anaerobic metabolism far too earlier.

However (in fit healthy people) at rest and low intensity exercise the body uses the aerobic system, and only switches to anaerobic when the aerobic system is unable to supply enough energy. This is standard exercise physiology in healthy people obviously, it seems strange that in ME/CFS sufferers the body starts in anaerobic metabolism and then goes in to aerobic. As I say I will look through the information on the link you provided.

The exact point that this change-over happens can only accurately be determined in a lab, but if you try breathing through you nose, and steadily increase the intensity of the exercise, the point at which this nose breathing becomes noisy and laboured, and you can’t hold a conversation any more, is a decent approximation. Over years of athletic training you can get used to feeling this point quite easily. This is the method I now use.

As I say by keeping myself in this aerobic zone I can exercise for a decent length of time, but if I go anaerobic (higher intensity exercise) I will suffer for it. So now I have recovered enough that I can get out and enjoy myself, but my days of racing and serious alpine mountaineering are regrettably over.

Hi Waiting, I might be ruffling a few feathers here, but I somewhat disagree.

Limiting your heart rate below your anaerobic threshold isn’t necessarily going to protect you from any sort of post exertional consequences but it will necessarily lead to lower exercise capacity at the anaerobic threshold. The level of fitness that the body maintains from a week to week basis is based on the weekly intensity peaks of activity. So my advice is not to limit the heart rate, but rather, to exceed it in a controlled manner doing some sort of intense activity, but only for a very short period of time and less frequently (say, once a week) and rest afterwards.

It is also not true that we use anaerobic metabolism for up to 2 minutes. In fact we use a mix of aerobic and anaerobic metabolism all the time, depending on the required work output which in turn recruits a mix of muscle fibres (there is a Gaussian distribution of twitch time of muscle fibres, with shorter twitch fibres using a different mix of metabolism and more fatiguable).

If you walk for 10 seconds at low intensity, you will still mostly be relying on aerobic metabolism.

Probably Workwell is referring to the use of (phospho) creatine as an energy buffer. When we increase exercise intensity quickly, aerobic metabolism can’t immediately follow and even anaerobic metabolism is slow to pick up.

It is during that time that creatine kicks in as a quick energy reserve. It is kind of “stored ATP”. Depending on the activity and the change in activity it can last for *up to* 2 minutes.

So, as long as you stay in that buffer, you don’t put high demands on glycolysis or the mitochondria. After that, sufficient rest is needed to replenish the buffer. That may take quite some time in the more severe ill.

The creatine buffer is replenished with *excess* energy and that is something we are short on.

Hi there Waiting,

Just read your post on the “broken” Aerobic Metabolism on PWME, who seem to be relying more on Anaerobic Metabolism than Aerobic. That makes sense since Anaerobic produces far less energy from 1 Molecule of Glucose (just 2 ATP + 2 Lactate) as opposed to Aerobic which produces 34-36 ATP from 1 Mol of Glucose (Krebs/Citric Acid Cycle)

My thoughts are:

– Why do PWME seemingly rely greater on Anaerobic energy production? We know we have low systemic oxygen/hypoxia, so that may also point to a primary Anaerobic energy reliance

– PEM: When PWME push their bodies to exercise/or any activity, is this unwelcome energy demand further complicating things by going through the Cori Cycle (where the muscles push lactate into the liver, in an effort to get more glucose?). The Cori Cycle is nett energy negative, and results in -4 ATP. Can this be further deteriorating body systems, energy problems after activity in pwme?

– Is this primary Anaerobic reliance causing further problems in Pyruvate uptake into Mitochondria ? Is this causing more complications in reaching Aerobic production?

– And finally: Whats the driving mechanism behind this “Anaerobic Cyclical Trap” that we are seemingly stuck in?

Would be great to hear any thoughts on this. Thanks

I was wondering if anyone has done a chemical stress test and if they did was there a crash afterward.

Thanks Cort for another great article!

I’ve done two of them. Both times reasons to need them and mostly mast cell related. So not knowing if the mast cell issues caused crash and stress test added to it or not. But they do give a medicine to slow down the heart, when they initially speed it up. And they monitor you very carefully the whole time.

Can we be sure these PEM phenomena are unique to cfs? Does anyone know if people with other inflammatory disorders suffer from? For example, rheumatoid arthritis has high prevalence of fatigue, do people with RA get PEM too? Just curious as to whether it is really ‘unique’ to cfs

This is a reply for Sniw Leopard’s comment — there was no reply button — here’s a Workwell paper that explains it better than I could. See Figure 9 for a graph of the metabolic pathways — anaerobic & aerobic.

https://academic.oup.com/ptj/article/90/4/602/2888236

You’re right that both pathways are in use all the time but anaerobic pathways dominate in the first 2 minutes, then at the anaerobic threshold.

To Cort: I found this a particularly useful newsletter, for summarizing so well and clearly what has already been written here and there about exercise testing, PEM, etc, and for covering this new study and what it adds to knowledge. Thanks so much. I agree with those who say we need treatments, but how are we going to get treatments until we really, really, understand what is going on and have consensus from the medical community. Also, I was completely dependent on disability insurance when I first got sick and feel that anything that helps people disabled with CFS to persuade the insurance companies to pay up is worth while.

Cort, I don’t see a significant increase in lactate level in CPET2 for CFS patients. It was +0.1mM (p=0.12) at LT (Fig 6D), which is practically same as CPET1. Perhaps you meant the difference at LT between patients and controls was significant? I don’t see so much deterioration in patients as failure to improve.

In any event, the increased lactate level probably is not the cause of PEM since lactate should clear relatively quickly whereas PEM lasts days to weeks. It’s likely that PEM sickness is the cause of the inability to improve on CPET2 rather than the other way around. It nonetheless is an interesting finding that could serve as another hint about CFS along with many anomalies.

Which brings me to this question: how does VO2max or lactate performance change when a person get sick? I’d guess that 2-day CPET tests on a healthy person before/after getting sick would look similar to that those of CFS patients.

I’m glad to see that this study at least took the pain to make sure that the patients and controls are matched conditioning-wise. Too often studies compare deconditioned patients with healthy control leaving the question about the conditioning factor.

Yes. You’re right. I got the lactate issue right in the body of the blog but misspoke in the conclusion.

There were several La findings. Laa at any power level was significantly increased in the ME/CFS patients. La per power output decreased in the healthy controls and increased in the ME/CFS during the second CPET but you’re right Laa was not increased in ME/CFS at the second CPET but was reduced in the healthy controls.

I took the exercise test in 2015 at the Hunter-Hopkins Center in Charlotte, NC ( w/ Dr. Charles Lapp). My results were so severe on the first day, they would not repeat the test on day two. In the 4 years since, I am mostly home bound. I don’t know if I could even complete the test now. Many factors have contributed to my decline, so I don’t want others to think the test alone caused my current health status. It was also a critical piece of “objective” data that proved my disability. Requiring a test that can cause your health to deteriorate is indeed cruel. Hopefully, one day, we will no longer need an exercise to access our ME/CFS status!

Here is a bit in Lien et al. that many might have missed:

“Neither the respiratory exchange rate nor the heart rate at GET differed significantly between groups or the CPETs (data not shown).”

Between the Gas Exchange Threshold (VT1) and the Respiratory Compensation threshold (VT2), is a relatively isocapnic period due to carbonate buffering of lactate acidosis.

The VO2Peaks were also similar between the two days.

All of this means that the recently rehashed hypothesis that the VO2 findings in CFS patients are due to hyperventilation is inconsistent with the evidence. (Melamed et al. 2019) https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs00421-019-04222-6?fbclid=IwAR1kSSCdLXW_P6MqhBI3x1AJxHR57iq_PnsL23S50R6NTBzAAd1AmOrn4SQ

But wait, there is more! There is another popular hypothesis amongst a certain crowd that CFS is a dysregulation of effort perception. The problem with this hypothesis is that it too is inconsistent with the 2 day CPET study results. Now it is important to point out that effort perception is not dependent on peripheral sensation (Helmholz was right!), but rather, the level central neural drive. However baseline effort perception on relative scales can still be altered by questionnaire answering biases, including sensations of pain. What is important therefore, is the relative curve during a graded exercise test, e.g. a CPET. What is interesting is that reported muscle effort as measured on the Borg scale increases significantly at around VT1 in almost all adult participants, regardless of age, disease, whether they are an athlete or not. The same is true for CFS participants in the 2 Day CPET, namely the sharp increase occurred earlier and coincided with the reduced performance at VT1.

The lactate findings of Lien et al. could simply be a consequence, not a cause.

Now anyone who has been paying close attention may have already realised what I am hinting here.

Here is the first hint, anyone remeber this study?

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12914560 (one of the non-CFS studies by Yves Jammes.

Here is another hint:

https://journals.plos.org/ploscompbiol/article?id=10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005581 (steady state model)

Actually I noticed that too. But this is a small study involving 17 patients in moderate to mild end of spectrum with aerobic conditioning matching the controls. So I wouldn’t write off VO2max studies till the result is repeated in a bigger trial.

I’d agree with the possibility though, that the exercise/lactic profile of CFS could be a consequence and not the cause of CFS/PEM. For one thing, moderate/mild patients do constantly suffer from ambient fatigue and ache, and yet their baseline lactic level is the same as the healthy control. So arterial lactic acid can’t be the (primary) cause of the primary symptoms at least.

Sorry – I’m kinda dumb; what are you hinting at?

These exercise studies only involve a small percentage of CFS/ME people–those who are willing and able to do them.

I would never agree to any exercise test, because I know I would collapse quickly and possibly never recover. I made myself much worse several by doing exercise that I enjoyed and felt able to do–and I never recovered from some of it.

These studies produce a lot of useful information. But we need to remember that because they only involve a very small group of people, they’re not representative of all of us. Their results may not be accurate for everybody

While many people cannot or will not do them I don’t know why their results – a reduction in one’s ability to produce energy after exercise would not apply to everyone. That is, after all, a core characteristic of this disease.

I think they’re probably quite representative. Hundreds of people have taken these tests. While some people obviously can’t do the test I know one person who is able tolerate only very low levels of activity who successfully completed them. I would think she would be representative of many very ill people. Her energy levels were significantly diminished on the second test. While we can’t know how more ill people would fare I think the results make sense for everyone.

Interesting study Cort. Thanks for reviewing. Unfortunately, there a few but significant problems with the methods of the study. In particular point, they may have controlled for total body weight, but it’s the lean body mass that would be more pressing to assess and to use as a control variable. The basic premise of an exercise test and LT, is that the onset of blood-lactate accumulation during exercise is a marker of nonsustainable work rates being reached, and the work rate at which it occurs is a measure of fitness. The mechanisms by which blood-lactate accumulation occurs during exercise even in healthy folks is not precisely known (of which, by the way, makes answering the “why” difficult in patient groups with potential differences), but it is determined by many factors including: the mass of exercising muscle; supply of oxygen to that muscle in blood; diffusion into cells; and the efficiency of utilisation by those muscle cells. So, they did not prove the difference in lactate threshold was not due to deconditioning because they did not measure or control for lean muscle mass. If the ME/CFS group had higher body fat and less muscle mass, then they have a different metabolic response to exercise. What was odd about the study, is the control group only exercised at most once a week. Perhaps this was a skewed way to control for both groups being deconditioned? But they don’t mention the level of activity that the healthy control group had. Exercises is one way of maintaining lean muscle mass, but one can simply be very active and that needs to be accounted for. Folks with ME/CFS not only have a lack of exercise but also a lack of overall daily activity. The study could’ve been greatly strengthened by also controlling for total body fat and muscle mass.

I’d agree with this. They made an effort to match aerobic conditioning like hemoglobin counts and breathing reserve, but that is not the entire measure of fitness. Other measures like muscle mass/strength and endurance are left out. Mismatched fitness could explain higher lactic production during exercise, though that still wouldn’t explain the discrepancy in CPET2: even unfit person should improve the lactic performance on the second day as long as they are healthy.

I don’t think anyone in an ME/CFS exercise study has ever controlled for total body fat and muscle mass. Is that a hard thing to do?

Even a deconditioned person, though, shouldn’t evidence a drop in VO2 max at GET or anaerobic threshold?

Hi Cort. No, it is not hard to do, to measure body fat and lean muscle mass. They are very unsophisticated to more sophisticated ways to do this. It’s an important thing to do though, because muscle mass has such a strong contribution to exercise tolerance and the way our energy is metabolized. The other thing that would useful is better measures of effort. Such as using EMG measures of muscle activation. It will be a hard sell to the “traditional“ physician who knows a little bit about physiology, or maybe even not, without these two basic measures added on to an exercise test. Also, it’s a very small study. I’ll have to take a look, but I’m wondering if anybody ever tried an ergometer physical fitness test. That’s just using arms versus your legs. Would be interesting actually to compare arms versus legs just an ME/CFS patients. The quadriceps are a huge reserve of muscle mass and therefore metabolism in all people. I am also wondering if it might be a “safer“ test in persons with ME/CFS and looking at PEM.

Controlling for muscle mass and body fat won’t control for fitness. The best measure of cardiovascular fitness, strangely enough is VO2max. Activity levels will only weakly correlate at best, because it is intensity that matters in maintaining fitness. For that matter, controlling for blood haemoglobin and blood volume is much more important than controlling for muscle mass, since these are key variables in limiting VO2Max.

But controlling for fitness doesn’t really matter for the findings in Lien et al. If you look at the distribution of the lactate data, there is substantial overlap anyway, so one cannot claim that lactate is causing the impairment in performance.

However the change in lactate was much higher for patients than controls, but there is still overlap!

The key finding therefore is that the lactate increased earlier, at a lower level of performance on the second day, compared to the first and this finding isn’t really dependent on matching fitness between patients and controls.

Oh and Neilly Buckalew, EMG activation would indeed be very interesting, that is something I was hinting at…

So I have been diagnosed with FM. Over time I’ve noticed the following…exercise day 1, say 12000 steps, then flare and mostly bed ridden for few days, takes awhile for flare to subside. Try to exercise again, but this time it only takes roughly half the amount to send me into flare. Although I’ve tried waiting longer between periods in order to recuperate, it seems that my ability is almost halved from the previous time. Quite frightening to see yourself decline this way. Now, I refuse to over exert because I’m getting worse with time and exertion. Anyone else in this predicament?

Hi Agnes,

Did you see the link to the Work well latest news above in Waiting’s reply to Ian on Oct 12 at 8.26am?

They give their ‘Understanding Graded Exercise Part 1’ in a short 8 mins video, which may be related to your situation? As in it’s not good to exercise beyond your limit, which for some people may be very, very low…

Thank you Tracey!

Yep, that sounds typical to me. 12000 steps is A LOT and I don’t think it’s unusual to take weeks to get back to where you were even after initial flareup subsides. I’d be rich if I had a nickel for every time I thought my time in the penalty box was over after a few days, only to keel over again. (I never learn, LOL.) I did learn to lay low and abide my time during the extended worsening though.

Yeah tk, if I manage 3000 now that’s extreme.

Snow Leopard, thanks for your comment. Perhaps you misunderstood my comment. The study already control for total body weight to show that this variable did not explain the difference in fitness – according to their analysis. They used an incorrect measurement. They should’ve used lean muscle mass not total body weight. It is incorrect to say that muscle mass is not factor in or a measure of fitness. It is indeed, particularly with ability to generate and sustain power. Without going into a dissertation about measures of fitness and energy cycles, as pointed out fat and muscle does make a difference in metabolic processes.

Neilly, I still haven’t seen a strong argument from anyone as to why fitness needs to be tightly controlled in this study? I see Cort more or less asked this same question. On a 2 Day CPET, participants are self-controlled, it is the within sample differences that are notable in this study, rather than the differences in group means.

Measuring body weight isn’t intended to control for fitness, it is measured because VO2 is typically expressed relative to weight since it is power to weight that matters in athletic performance. The most effective measure to control for fitness would simply mean similar VO2Max between patients and controls.

But the question still remains. What effect does lean muscle mass (given similar body mass) have on lactate production? Not much as it turns out.

https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0095797

Is CFS/ M.E. really the only condition that has PEM/ these metabolic abnormalities? What about the recent article on those who get over-training syndrome? Are there *any* other conditions with these similar metabolic markers, even if rare?

Lactate has been implicated as the culprit in previous studies too, though they were small studies like this one. My understanding is that Lactate (which is a product of Anaerobic Energy Metabolism) is produced in higher quantities in pwme, due to primary Anaerobic Metabolism, which seems to have replaced, in part, Aerobic Metabolism.

– Anaerobic Energy production (without oxygen) is far less productive when compared to Aerobic (with oxygen)

– In Anaerobic Energy Metabolism = 1 Glucose = 2 Pyruvate = 2 Lactate (Pain!) + 2 ATP

– Aerobic Energy Metabolism = 1 Glucose = 2 Pyruvate = 34-36 ATP + CO2 + no lactate!

– I also suspect that in times of increased energy demand in pwme, our muscles (which are pushed to produce energy) use Lactate to produce glucose through the liver (via Cori Cycle), but the Cori Cycle results in a net of – 4 ATP, ie negative 4 ATP (it consumes more ATP than it can produce). So essentially, it is energy negative, sucking more energy out of the body.

– Could the Cori Cycle result in complex and prolonged symptoms of PEM from which takes weeks or months to recover (since it is nett energy negative)? This along with increased Lactate may lead to more pain and much more reduced energy as compared to before the activity/exercise?

– Low systemic Oxygen/Hypoxia/Low Oxygen Uptake ability is already known in ME CFS. Could this be resulting in further problems, causing a downward spiral triggered by activity/exercise.?