Bhupesh Prusty is good at making waves. He and Bob Naviaux raised eyebrows in 2020 when their study showed that an HHV-6 infection might not only be damaging the mitochondria – putting the cell into a cell danger state – but also appeared to cause the cell to be pumping something into the serum that was doing the same thing to other cells.

Then last year, Prusty found that miRNAs produced by herpesvirus-infected cells were at least in part responsible for the mitochondrial fragmentation found. Plus in a small autopsy study he found evidence of widespread HHV-6/EBV activation across the brains of people with ME/CFS.

An enthusiastic researcher Prusty primed the pump in the weeks leading up to the Charite and Invest in ME conference he recently presented at on his Twitter account stating:

“We will announce a biomarker for #MECFS and #LongCovid very soon. A very interesting piece of the puzzle to unfold in coming weeks. Knowingly I did not use the word ‘Novel Biomarker’ as a lot is known about it and that is actually a very good news. Fingers crossed!”

I saw Prusty’s presentation at the Charité conference, but it was so complex that I got completely lost halfway through. How good it was, then, to find (thanks to Jutta) the TLC Living with Long-COVID podcast where Prusty talked about his recent findings. Without that podcast, which focused on what appears to be a very large paper with multiple authors and multiple cohorts that was recently submitted, this blog would not exist.

A Focus on Herpesviruses

Prusty at the Charité Conference in Germany.

Prusty has followed a somewhat different path than some other researchers. While some researchers have been gathering data that they hope will get at the cause of chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS), Prusty, a molecular virologist, came at ME/CFS with a hypothesis – that herpesviruses were playing a huge role in it. Given that hypothesis, he tried to understand how – contrary to the evidence that had been gathered thus far – that was so.

Prusty was faced with a challenge. Herpesvirus reactivation, or primary infection in the form of infectious mononucleosis/glandular fever, appeared to be happening in ME/CFS, but studies had generally failed to find evidence of a high viral load. (A 2020 study did, however, find evidence of EBV reactivation in 25-66% of ME/CFS patients.) That left a question – how could a virus that wasn’t replicating and didn’t appear to be all that present (in the blood, at least) be causing something as devastating as ME/CFS?

While Prusty was showing that, at least in lab cultures, herpesviruses could fragment the mitochondria in the cells they were found in – and possibly even in the cells they hadn’t infected, researchers at Ohio State University were digging deep into the EBV question in ME/CFS.

Over the past ten years or so, Marshall Williams and Maria Ariza had, in a long series of NIH-funded studies, had been showing that EBV didn’t need to replicate at all to potentially cause problems. All that was needed was to produce a kind of smoldering, aborted infection that got started but never made it to the replication phase.

They found that in a large subset of ME/CFS patients, EBV was producing a protein called EBV duTPase that: a) appeared to be capable of sending their immune systems into a tizzy; b) could be triggering an autoimmune reaction; and c) might even be contributing to neuroinflammation. Later, they added HHV-6 duTPase to the list.

Prusty, Ariza, and Williams got together to see if an antibody response to the EBV and HHV-6 duATPases was present that would indicate that the immune system was fighting it off. Note that the immune response to a virus or protein can be a bigger problem than the presence of the virus or the protein itself.

The high antibody levels against every dUTPase tested (EBV, HHV-6, HSV-1) in ME/CFS suggested that aborted herpesvirus infections of all kinds (but particularly our old friend EBV) are present in this disease (!), in my mind at least, dramatically upping the potential role these enzymes are playing in ME/CFS.

HSV-1. While the immune responses to the herpesvirus dTUPases were not as pronounced in long COVID as in ME/CFS, a strong immune response was mounted against the HSV-1 dUTPase.

Things were a little calmer in the long-COVID world where a significantly higher IgG response was found against HSV-1 dUTPase as well as a higher, but not statistically significant, EBV response. One wonders if long-COVID patients simply need more time to develop the full range of aborted, but still active, herpesvirus infections seen in ME/CFS, but then came a weird finding – the kind of finding that doesn’t seem to make sense. The antibody response to HHV-6 dUTPAse was actually lower in the long-COVID patients. Prusty suggested that potential differences in T and B cell response in ME/CFS and long COVID might be responsible.

The Herpesvirus dUTPases – Mitochondrial Disrupters

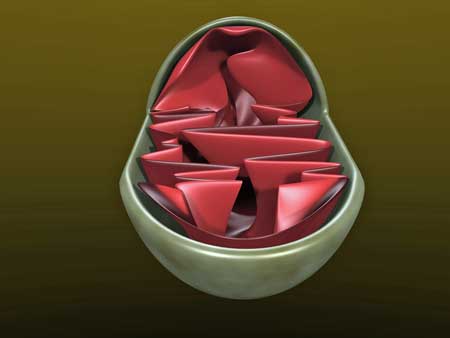

We can now apparently add mitochondrial dysregulation to the increasing list of problems that these herpesvirus dUTPase proteins may be producing. When the researchers inserted dUTPase inside the endothelial cells, they found high levels of hyperpolarized, hyperfused mitochondria; i.e. the same types of mitochondria Prusty and Naviaux found in their earlier herpesvirus studies.

The herpesvirus dUTPase enzymes were like kryptonite to the mitochondria – each one caused them to clump, resulting in impaired autophagy.

All the dUTPases they assessed – whether they were from EBV, HHV-6, or HSV-1 – produced some major damage by disrupting the cytoskeleton or backbone of the mitochondria. That structural disruption, in turn, apparently changed the morphology or shape of the mitochondria. In biology, a simple thing like a change in shape can be determinative. The body may not, for instance, recognize it anymore, it may not function properly, and/or the body might try to attack it.

In this case, it appears it is at least having trouble trying to get rid of them. Prusty reported that clumped mitochondria are not being recycled properly. That’s an interesting finding, given the Simmaron Research team’s findings of reduced autophagy or mitochondrial clean-up in ME/CFS. He also noted that these clumped mitochondria are found in many different kinds of neurological diseases – which is a potentially good sign for the small ME/CFS field, which can’t begin to fully track down all its potential leads.

Prusty noted that prolonged periods of herpesvirus reactivation are known to increase the risk of autoimmunity. Autoantibodies, he said, are increased during COVID-19 and long COVID (some research does not show this) and have been found in ME/CFS.

IgM Antibodies to the Fore

The next step was to attempt to differentiate mild/moderate/severe ME/CFS patients from healthy controls using the IgG and IgM response against 120 autoantigens – bits of proteins known to trigger an immune (antibody) response. Plus, they looked for 120 associated autoantigens associated with pathogens. Prusty noted this was “a very small proof of concept study”.

There was no difference in the IgG response, but they found that high levels of autoantibodies associated with an IgM response against a variety of factors, including c-reactive protein (CRP), collagen 5,6; ss/ds DNA – (associated with lupus and multiple sclerosis) were found in the ME/CFS group, and that they did differentiate between the healthy controls and mild, moderate and severe ME/CFS patients. That broad-based difference was encouraging … as was the obvious potential autoimmune connection.

As interesting as those factors were, Prusty didn’t dwell on them. Instead, he focused on an IgM autoantibody called fibronectin that was low in ME/CFS and which he said correlated well with the severity of the disease; i.e. the more severe the patients, the lower the IgM fibronectin autobody levels.

Next, Prusty focused on the great question – how could the localized herpesvirus infections that he believes are present cause such widespread problems? The only possibility he could think of was that the viruses were dumping something into the blood or serum.

Several studies and findings – Prusty’s included – do indeed suggest something in the serum may be causing ME/CFS (and FM). That something – as has been suggested in fibromyalgia by Goebel – could be antibodies (immunoglobulins) that are reacting against something that has gone wrong in the cell – and are then getting pumped out of the cell – and disturbing other cells. It’s these antibodies that treatments like apheresis and immunoadsorption are seeking to affect.

They then purified IgG immunoglobulins from 30 healthy controls and ME/CFS patients and put them into a variety of different cells. Most of the cells were not affected by the ME/CFS patient serum, but interestingly – very interestingly – the mitochondria in the endothelial cells that line the blood vessels became fragmented.

They were even able to link the mitochondrial fragmentation to a decrease in a mitochondrial protein that keeps the mitochondria intact – a nice sign that the finding is correct. Prusty cautioned that other factors than IgG may be fragmenting the mitochondria in ME/CFS, but we clearly have to add IgG to the list.

Because the IgG purification process is not completely effective, they then crossed their I’s and dotted their T’s by using a mass spectrometer to see if the ME/CFS immune complexes that made up the immunoglobulins contained other factors that might account for the changes they’d seen. Three proteins showed up – all of which were decreased in the ME/CFS patients.

Two Fibronectin Diseases?

They then zeroed in on fibronectin-1, one of the more severely decreased proteins. This protein is incorporated into the complement pathway where it plays a major role in the fight against infections. Low levels of fibronectin found in these immune complexes could potentially constitute a kind of immune hole that leaves patients vulnerable to pathogens. They could also, Prusty suggested, produce the symptoms of sickness behavior we see in ME/CFS even if no virus is present.

The next question was why such low levels of fibronectin were present in these immune complexes. Next came a big surprise. ME/CFS patients had higher – not lower – but significantly higher levels of fibronectin levels in the serum compared to the healthy controls. That suggested that the protein was abundant in the serum but for some reason was not being taken up by the immune complexes.

It got even more interesting. Using the functional Bell assessment as a measure of health, they found that more severe patients had even higher levels of fibronectin in their serum than the mild/moderate patients. (As patients got worse and worse, were their cells fruitlessly calling out for more and more fibronectin?)

However, while fibronectin levels did differentiate 80% of the severe ME/CFS patients from the healthy controls, Prusty noted that was not a significant enough difference to constitute a biomarker. Fibronectin, he thought, though, probably played a bigger role in ME/CFS than in long COVID.

Cellular fibronectin is a marker of inflammation, is found in many immune cells, and is very important in wound healing. Plasma fibronectin, on the other hand, plays a role in immune modulation, complement, mast cells, and anti-inflammation. High levels of plasma fibronectin could result in increased clotting, platelet, and mast cell activation, etc. Both cellular and plasma fibronectin were increased in ME/CFS serum. (Immune complex fibronectin, on the other hand, was decreased.)

Moving to long COVID, the same fibronectin finding showed up but not to the same extent, and Prusty suggested that as long COVID progresses over time it might become more substantial.

Gender differences are being explored more and more in ME/CFS and they are showing up in spades – and so they did in this study. Males, interestingly, tend to have lower fibronectin levels at baseline than females. That low fibronectin baseline combined with the much higher fibronectin levels in the ME/CFS patients made fibronectin a very significantly distinct factor in men.

In women, with their higher baseline fibronectin, the changes in fibronectin were not as distinct, but Prusty felt the naturally higher levels of fibronectin put females more at risk as they needed less fibronectin than males to reach “a pathological level” of the factor. If he’s right, he’s found a nice way to explain the gender divide in ME/CFS. It also suggests that it might take a more severe infection to tip men over into ME/CFS.

Depleted Natural IgM Antibodies – Could They Tell the Tale?

Natural IgM antibodies participate in a wide variety of processes in the body. Their levels were low in long COVID and may be low in ME/CFS. (Image rom Panda, 2015 – Journal of Immunology)

Prusty noted early infections in mice cause fibronectin in the blood to go up while IgM response to fibronectin goes down, and that old papers found that healthy individuals have high levels of IgM against fibronectin. This kind of pattern only shows up, he said, in natural antibodies that play a healthy role. These antibodies apparently function as a kind of cleanup or scavenger crew that removes dead cells before an autoimmune process can begin.

Prusty said “autoimmunity is clearly there” in ME/CFS, long COVID and SAR-CoV-2 patients. Not everybody would agree with that, but the team’s next task was to develop an assay that could assess the IgG and IgM antibody response against fibronectin. Did the high levels of fibronectin found in the plasma and serum of ME/CFS and long-COVID patients mean that the IgG/IgM response to it was reduced?

What they found, Prusty said, was “very, very interesting”. Only the severe ME/CFS patients had a reduced IgM response to fibronectin. In contrast, the mild, moderate, and severe long-COVID patients all had a significantly reduced IgM response to fibronectin. Even the mild patients – who had few symptoms – had significantly reduced IgM responses to fibronectin.

Prusty posited that the loss of the natural IgM response in long COVID to fibronectin doesn’t tank things immediately, but as the scavenging processes are lost, the dead cells and cellular debris build up and the body eventually produces an autoimmune response to them.

Akiko Iwasaki asked him what about the other IgM natural responses. Are they all going down? In what may be a novel finding in long COVID, further study suggested that the natural IgM population goes way down after a COVID-19 infection.

Natural IgM responses are produced by B-1 B cells. They play a variety of roles including “scavenger, protector, and regulator“. They play a big role in the complement arm of the immune system, help to knock down pathogens, and clean up dead cells. Because they bind to self-antigens, they provide a bulwark against an autoimmune response.

This suggests that the plasma B cells that produce these natural IgMs are being dramatically affected by the coronavirus. Over time, the B-1 cells in the recovered COVID-19 patients return to normal, but they do not in the long-COVID patients – the reduction in the natural IgM responses persist. The effect appears to be dramatic indeed: a comparison of the natural IgM levels in the long COVID to the recovered patients results in a 99% accurate diagnostic rate.

Prusty has also found very low IgM levels to fibronectin in ME/CFS but hasn’t checked the levels of other lgM natural antibodies. He noted that EBV duATPase could be producing a similar effect in the B-1 plasma cells in ME/CFS.

THE GIST

- Bhupesh Prusty is a dynamic researcher who has contributed enticing findings in ME/CFS in the past, including herpesvirus-infected cells which not only damage their own mitochondria but appear to do so in cells adjacent to them.

- Prior to his talks at two ME/CFS conferences recently, Prusty raised expectations with his announcement that he’d found a long-elusive biomarker for both ME/CFS and long COVID.

- This blog resulted from the TLC long COVID podcast in which Prusty talked about the findings from a large paper that was recently submitted.

- Prusty, a molecular virologist, came to ME/CFS with a hypothesis – that herpesviruses were playing a large role in it. The problem was, though, that the viral loads of herpesviruses in ME/CFS have never been particularly high.

- Enter the Williams/Ariza team at Ohio State University, which for the last decade has been showing that a smoldering EBV infection is present in ME/CFS that’s pumping out an enzyme called EBV dUTPase. Their studies suggest that this enzyme may be causing an immune reaction, producing autoimmunity, and even may be involved in neuroinflammation.

- Prusty and the Ohio State group teamed up to show that an immune response to all three herpesvirus (HSV-1, EBV, HHV-6) dUTPase enzymes was found in ME/CFS. In contrast, only an immune response to HSV-1 was present in long COVID. Either the long-COVID patients had yet to get all their herpesviruses involved or something very different was happening in that disease.

- We can add mitochondrial disruption to the rather long list of problems these enzymes may be producing. When the researchers inserted dUTPase inside the endothelial cells, they found it produced high levels of damaged, clumped mitochondria; i.e. the same type of mitochondria Prusty and Naviaux found in their earlier herpesvirus studies.

- These strangely shaped mitochondria – which Prusty said are commonly found in neurological diseases – are resistant to getting cleaned up and recycled. Interestingly – and encouragingly for both teams (and for ME/CFS), Simmaron’s research team has recently found evidence of impaired “autophagy”; i.e. mitochondrial cleanup in ME/CFS as well.

- Next, the Prusty group attempted to differentiate between ME/CFS, long COVID, and healthy controls by assessing the levels of pathogenic antigens (proteins that evoke an immune response) and antibodies (the immune response) to those antigens. Note that it’s often the antibody response that’s the most harmful.

- Several IgM antibodies most of which were associated with autoimmune diseases popped up, but the Prusty team was more interested in the reduced levels of an immune factor called fibronectin. This factor plays a role in pathogen defense, mast cell activation, inflammation, clotting, and platelet activation.

- Putting the antibodies (immune complexes) from ME/CFS patients into the endothelial cells that line the blood vessels added yet another way (miRNA, herpesvirus dUTPases) to fragment the mitochondria in ME/CFS.

- Because women typically have higher levels of fibronectin than men, Prusty questioned whether they may more easily reach “pathogenic” levels of the protein in the blood during an infection – leaving them more vulnerable to ME/CFS.

- Next, they did a deep dive into the immune antibody complexes in ME/CFS to find, lo and behold, low levels of fibronectin. Checking the blood, they found high levels of fibronectin there. Something was clearly interfering with fibronectin intake into the immune complexes. While fibronectin levels were altered in long COVID, they were clearly lower in ME/CFS.

- Next came a potentially crucial finding. The IgM antibodies to fibronectin are “natural” antibodies; i.e. they are naturally produced by the body to regulate fibronectin levels. Did the increased fibronectin levels in ME/CFS in particular mean that these natural antibodies were reduced? Yes, but only in the severe ME/CFS patients. Meanwhile, the entire cohort of long-COVID patients had reduced IgM antibodies.

- That set up an experiment where they looked at other natural IgM and found, in what appears to be a unique finding, that they were also depleted in long COVID. This set up a possible scenario where a widespread depletion of natural IgM antibodies causes long COVID.

- Because these antibodies specialize in removing dead and damaged cells, Prusty proposed that as these scavenging processes are lost, the dead cells and cellular debris build up and the body eventually produces an autoimmune response to them. They also suggest that the B-1 B cells that produce these antibodies are damaged in long COVID. Interestingly, the dUTPases found in ME/CFS may be able to damage these very cells as well.

- While Prusty found some differences between long COVID and ME/CFS, the alterations in fibronectin in both diseases constitute the biomarker he believes he’s found. The good news is that measuring fibronectin is a cheap and easy thing to do.

- One sore spot stuck out – the interviewer’s apparent belief that in contrast to ME/CFS in where symptoms slowly build over time, long COVID occurs more quickly. It’s true there’s a gradual onset subset in ME/CFS – and there’s one in long COVID as well – but that’s certainly not the experience of many people with ME/CFS who can remember the day their illness abruptly began.

- With regard to treatments, Prusty, who is not a clinician, mentioned things like IVIG – which will excite no one probably – as well as immunoadsorption, apheresis, and some others. Prusty, though, noted that these are complex multifactorial diseases that will likely require complex, multifactorial treatments.

- Prusty has done a lot of work, but his next step is looking for a new place for his lab as his current location is not providing sufficient support.

- The findings do not appear to be based on large studies and will need to be replicated. With his dUTPase results, Prusty has built on and enlarged past findings, and in his fibronectin and natural IgM antibody results, he’s introduced a new concept of how these diseases occur.

- Time, of course, will tell how this all works out. Hope that a new understanding of them has emerged, along with a suitable dose of caution as we await replication, would seem to be a good approach to take :).

ME/CFS vs Long COVID

Prusty noted the many clinical similarities between long COVID and ME/CFS. An analysis found that with regard to circulating fibronectin and low IgM responses to fibronectin, the ME/CFS patients, in particular, the severe ME/CFS patients and long-COVID patients, look more or less similar. The total similarity between all the long-COVID and all the ME/CFS patients is less but still significant, and there’s essentially no difference between the severe ME/CFS and severe long-COVID patients with regard to these factors.

In the long COVID patients, the decrease in natural IgM in response to the coronavirus is so clear that Prusty is not willing to bring herpesviruses into the equation. If he was to make a guess, though, he said he believes that herpesvirus reactivation does play something of a role. After all, he found antibodies to the herpesvirus duATPase protein in more than 50% of long-COVID patients and evidence of a strong reactivation of EBV and HSV-1.

Since he’s seeing similar fibronectin findings in ME/CFS and long COVID – and the ME/CFS patients haven’t been exposed to the SARS-CoV-2 virus – then it’s possible that herpesvirus reactivation is causing it, but that’s conjecture at this point. Nevertheless, the end product – problems with fibronectin – appears to be the same in both diseases.

A Slow Burn Disease?

The interviewers were great – they asked great questions and seemed able to follow along in a very complicated discussion quite well but at the end, one of them asked a strange question. Referencing the changes in IgM response to natural antibodies, she compared the almost immediate effect of the SARS-CoV-2 virus – which produced long COVID within 2 months of suffering – to the “much longer slower burn” of ME/CFS where their symptoms get worse over a longer period of time.

I have never heard ME/CFS referred to in that way before. While there is a gradual onset subset in ME/CFS (there is also one in long COVID), many people with ME/CFS can date their illness to the specific day they came down with the devastating cold they never got over. Their onset was dramatic and unforgettable.

In fact, given that we now know that long COVID can manifest without producing any symptoms during the initial infection, one could make the case that ME/CFS might, in some cases, actually manifest itself more quickly.

I don’t know where that idea came from, but I wonder if it speaks to some ideas in the long-COVID community that ME/CFS is somehow less damaging and less real.

Treatments

Prusty is not a clinician but feels potential treatment strategies exist. The most relevant, he thought, were IVIG and immunoadsorption, and mentioned apheresis, plasma B-cell therapy, bone marrow-derived cell transfusion, and recombinant B-cell therapy – among other things. That said, he also said that these diseases were complex and multifactorial and likely would require similarly multifactorial treatments.

A case certainly can and has been made for IVIG in ME/CFS, but it has been tried and my understanding is that the general results are pretty moderate. It is apparently possible, though, to create natural IgM-enriched IVIG – and the results of that could be different.

There was some good news regarding testing, however. Because a fibronectin assay can be readily and cheaply produced in any lab, we could quickly get a sense of its levels in ME/CFS. While a test to assess natural IgM antibodies is not commercially available, it could be produced quickly and easily by many labs.

Prusty said the next phase for him is not jumping into more study but, citing the lack of manpower, professional stability, lack of lab space, etc. in his current digs, he’s looking for a new home for his lab.

A paper with numerous co-authors including Ariza and Williams, and Carmen Scheibenbogen, and which includes multiple cohorts of ME/CFS and long COVID, may be out soon.

Conclusion

It was exciting to see Prusty join hands with the longstanding Ohio State University ME/CFS effort and discussing his work and getting recommendations from immunologists like Akiko Iwasaki and Tim Henrich. The Ohio State University effort pretty much flies below the radar in ME/CFS circles, but it’s consistently produced positive results and boasts what is easily the longest-standing NIH grant award – probably over ten years at this point – in the ME/CFS field.

Seeing increased antibody responses to all three herpesvirus dUTPases in ME/CFS was striking indeed, as was the finding that these early herpesvirus enzymes may be damaging the mitochondria. That said, the high immune responses to HSV-1 dUTPase, but reduced immune responses to HHV-6 dUTPase found in long COVID, suggested the two diseases might be parting ways at least early in the illness.

It was nice to see Prusty follow the thread – to find the low fibronectin levels in the immune complexes, then the high fibronectin levels in the serum, then the reduced IgM response to fibronectin, the possible autophagy connection, and then the biggie – the possible widespread depletion of natural IgM antibodies in COVID-19, and ultimately long COVID, which implicates the plasma B-1 B cells.

Prusty said he believes he has found a biomarker (others, he noted, disagree) but does not claim that the loss of the natural IgM responses is the complete cause of long COVID.

Time, of course, will tell whether Prusty has produced a beautiful hypothesis that gets dashed down or one which stands the test of time and provides a new opening for understanding both ME/CFS and long COVID. We should note that these initial studies appear to be quite small and replication is essential. We’ll know more when the paper comes out. Both hope and caution would seem to be in order.

Health Rising’s Summer Donation Drive!

Our commitment is to as fully as possible explore the possibilities present in these diseases. If that’s what you want to see, please support us!

33 long years ago I had sudden and severe onset of ME/CFS. (I did have a good 15 years of mild ME/CFS in the middle of that, only to be drastically permanent and severely worsened by an influenza vaccination eight years ago)

Anyway most people I’ve discussed the disease with in person and online about their ME/CFS, described it as starting with sudden onset

I can count on one hand those who had a slow gradual onset.

That question asked is eyebrow raising because it’s long been accepted that the majority of ME/CFS onset is rapid.

I guess I’ll get a lot of replies from people with slow onset, I am well aware they exist too.

Is it possible to have both a gradual and sudden onset of ME/CFS? I feel as though I have. The gradual onset obviously began with mild symptoms and (gradually) worsened to more moderate symptoms. The sudden onset was a severe smack in the face and punch to the gut.

I think there are a multitude of onsets in this disease. I would be surprised if the same wasn’t happening in long COVID.

Thanks as always Cort. However I really don’t buy this.

I’ve always put myself in the gradual onset group mostly because my ME/CFS didn’t start with a normal flu-like event. It did however happen pretty quickly – it started sometime in the middle of the quarter in college and by the end of it I was in bad shape. I now wonder, though, if I simply had an atypical case of infectious mononucleosis which presented with muscle pain and fatigue.

There are all sorts of patterns, though. Some people get sick, get better and then get sick again like you did. I imagine the same thing is happening in long COVID. Some people are coming down with say, a mild case, get better and then get taken down by another bug or by a stressful event or by trying to do too much or things like that.

I hope someone is charting these things with a fine-toothed comb in long COVID. It would tell us much.

It could also be that those that have the mild onset continue to try to live life the way they did and all that pushing through worsened the disease bit by bit?

Yes I hope it’s being charted too! As I also wonder after hearing that in a significant minority of cases of Long Covid, that the patient can’t remember even having had a Covid infection, yet their test results showed a recent encounter with SARS-CoV-2 i.e. they were asymptomatic yet still developed an ME/CFS like disease

Which could mean that those with ME/CFS who can’t remember any infectious onset (I heard it’s around 20%?) quite possibly actually had a viral infection but just not apparent enough to physically feel it, but was enough to put the person’s immune system to the test. Especially the viruses that take longer to defeat, as the stressor’s duration seems to be a factor too.

Because at any given time everyone of us is fighting off some bug or virus that’s trying to enter our system. We just don’t feel everyone of them.

Maybe the 20% group that slowly decline into ME/CFS depends on the type of virus to tip a person. And/or maybe it takes some people to have several asymptomatic infections in my a row, or even a vaccination around the time also helps tip the balance. (I’m pro-vaccination, but am wary for some with ME/CFS)

I remember Jarred Younger from ‘Younger Labs’ said it could be several immune hits in a too short a time period can push a person into ME/CFS.

Often we hear of people who went overseas travelling and came home with ME/CFS, Was that the combination of several new infections and all the various travel related vaccinations all around the same time, just too many hits for an immune system prone to ME/CFS to handle.

All that said though, it goes to show that Long Covid and ME/CFS both have sudden onset and gradual onset. Even staggered worsening. (Although the earlier a person tends to improve the better their outcome ) but if they are sick at 3 years, I bet we will see Long Covid patients that met the Canadian Consensus Criteria for ME/CFS which is 50% (source MedScape) will become locked into the disease too.

Looks like the same disease for them, especially those who have Long Covid with PEM, in my view that’s ME/CFS, (unless they are steadily improving like many do with Post Viral Fatigue Syndrome ‘PVFS’)

Those who recover from PVFS are the people I would be interested in knowing why they get better after several months. Because they hold the key, as they have a mechanism that brings them back to a healthy homeostasis.

Although I’ve heard of people who previously had PVFS, who then years later when the pandemic arrived they developed Long Covid.

Gez Medinger who has an excellent YouTube channel on Long Covid, had PVFS several years prior to Long Covid, he fully recovered from the initial PVFS, but when he caught Covid 3 years ago, he remains still sick with Long Covid to this day. Meaning the stressor this time was too great, and/or his age may have changed his immune response.

“It could also be that those that have the mild onset continue to try to live life the way they did and all that pushing through worsened the disease bit by bit?” Yeah.

Well, I am gradual onset, 2 relatives are as well. I think gradual cases, particularly in their mild initial stage, probably get masked up much more easily under psychosomatic diagnoses because with gradual onset they look more like it. While I had immediate onset pain PEM early on, it took me years to “bloom” into the full picture of true next-day PEM. I guess that in every psychiatrists patient base there are likely a number of ME/CFS gradual onset cases hidden behind depression and somatoform disorder diagnoses. There is also that subgroup I belong to where stress has been a likely onset co-factor, and I believe that because stress can also trigger psychological illness and because there are forms of preexisting depression that can be inflammation related, separate psychological comorbidities might be more common in that subgroup, making gradual onset ME/CFS even harder to spot where it exists in a mixed picture next to true psychological diagnoses in a person.

This makes me assume there is likely a big “dark figure” of mild to moderate gradual onset. Maybe it also depends on what crowd you connect with. I sometimes think that numbers of ME/CFS ambulances might be skewed because moderate to severe patients would be most likely to make it there, but neither the bedbound very severe, nor the mild-to-moderate who might not yet have recognized they have ME/CFS, or whose gradual onset might not yet have developed into the full picture of ME/CFS. And studies might prefer to pick cases with a clear onset event.

I was pleased so see Prusty mention somewhere that stress can trigger HHV6 reactivation.

Once you start thinking about things, it starts to look like ME/CFS is everywhere.

Then I learned some physiology and bioenergetics and realize that it’s hypothyroidism/hypometabolism that most are suffering from, together with nutritional deficiencies.

That allows you then to start treating it as such and regain health.

I had sudden onset of ME/CFS in 2000 (I had what I thought was a mild ’flu that just continued to get worse, minus the respiratory symptoms and fever). I was able to continue working but only just barely. Then what I thought was full recovery in less than a year that lasted 12 years. “Full” in the sense that I was able to continue normal life without pacing, although insomnia has plagued me up to the present time. But I thought that was unrelated. A couple of brief relapses lasting a couple of months and separated by years of remission, then what I am pretty sure was Covid in early 2020, followed by Long Covid. Three years later, no recovery just ME/CFS. I’m doing the best I can but I do not expect another remission. I think this is a highly variable disease, and like MS can take take various forms. But once you get into the progressive phase, there is no more remission.

Thank you for summarizing Cort! I am both encouraged and discouraged by these findings. I’m encouraged because this research feels like it is heading in the right direction.

My CFS journey started with a mono/glandular fever infection and it just makes sense that EBV is somehow involved. If herpesviruses can linger long after an infection and cause significant damage to mitochondria all over the body, that would certainly explain why CFS patients are exhausted all the time.

If fibronectin plays a role in CFS and baseline levels (in healthy patients) vary significantly by gender, that could help explain why CFS is more common among women. The initial research highlights interesting avenues for exploration and I’m hopeful labs will create new tests to evaluate fibronectin, dUTPases, and other abnormalities. Onward and upward!

That being said, I’m also discouraged by these findings because I feel like Prusty overpromised. On March 30th, Prusty tweeted that his team had discovered a biomarker for CFS. When someone asked him if bigger trials would be needed to validate his findings, Prusty said: “No bigger trial required. We are already trying it on a larger patient cohort with beautiful results.”

But, from reading your article, it sounds like Prusty doesn’t actually have a confirmed biomarker (he just has a hypothesis). And the sample sizes from his research were small enough that others will need to replicate his work at-scale to see if his findings are actually reliable.

I’m grateful Prusty is working on CFS research, but it feels like he shouted something from the mountaintop that wasn’t entirely true and that’s disappointing because the CFS community has already been disappointed by the medical community so, so many times.

I know Prusty is looking for a new employer, so perhaps he wanted to garner as much attention for himself as possible by making bold statements, but I personally would have really appreciated it if his initial tweet had said “We have an interesting hypothesis about a possible biomarker for CFS. We’ll be sharing our research soon so others can test the hypothesis.” As opposed to “We will announce a biomarker for #MECFS and #LongCovid very soon.”

We’ll see in the paper how big those cohorts are. It seems that the key is big enough cohorts – I don’t know how big (lol) – in several patient groups – and ultimately validation by other researchers is necessary for a finding to really take hold. I believe Prusty had several groups but I have no idea what parts of his hypothesis were tested in those groups – so we’ll see. I’m hopeful that other research groups will attempt to confirm his findings. Sometimes it happens in ME/CFS and sometimes it doesn’t.

My feelings exactly!

You don’t seem to understand the definition of a biomarker. There are already about a dozen biomarkers for ME/CFS and some have been present for decades, eg: https://me-pedia.org/wiki/Diagnostic_biomarker. Prusty himself never said it was a *unique* biomarker exclusive to ME/CFS. But it’s not entirely your fault as the hype around Prusty’s statements made it seem like it was; People just assumed that. But I do think that it is strange/novel enough that it could rule in ME/CFS when taking into account symptoms & history. Nevertheless, Prusty’s research & biomarker has revealed novel discoveries and opened many new avenues for further research. So I would argue he did delivery.

When Prusty tweeted two months ago “We will announce a biomarker for #MECFS and #LongCovid very soon” I took that to mean “We found a lab test that will objectively and reliably deliver a diagnosis of ME/CFS.” Admittedly, I am not a doctor or a scientist, and Twitter is not a great forum for nuanced conversation. Either way, the website you shared offers a definition for biomarkers that matches my expectations: “A diagnostic biomarker refers to a biological measure that aids the diagnosis of a disease and may serve in determining disease progression and/or success of treatment. It may be a laboratory, radiological, genetic, anatomical, physiological or other finding that helps to differentiate one disease from others.” I know there are other theoretical biomarkers for ME/CFS patients, but it’s my understanding that none of them are widely used. I am a severe patient who receives care from Stanford (in the USA), and they diagnosed me via a questionnaire and a review of my medical history. Someday, I hope there will be an objective test that is the gold standard for the industry and it proves someone has ME/CFS beyond the shadow of a doubt. That would add legitimacy to this illness and relieve some of the burden on our community. I’m rooting for Prusty to succeed and I hope the issues he’s surfaced lead to meaningful breakthroughs.

Yes, Thomas, it’s ridiculous that we are still being diagnosed by questionnaires. And I concur that Prusty has thus far under-delivered on his promises. He claims, “If I say one thing, it means I know 10 things.” So, time will tell – he will (soon, hopefully) publish his research and perhaps share more insight. At this point, though, the model is unsatisfying.

How does this explain PEM?

What about enteroviruses? Or other pathogens? Does it always come back to herpes virus reactivation? Or is there a role for other viral persistence?

There are many anecdotes of overnight remissions/cures; if there is a switch, how do we reset the switch? Prusty says it is too complex for that, and that treatment will be multi-faceted and lengthy. Really?

In the referenced podcast (I think), Prusty talks about bone marrow infection by herpes. There’s no mention of that here. Does that explain a certain sub-type?

What about vagus nerve involvement? A lot of people – especially hippy chicks and that VanElzakker dude who hasn’t done any work in 8 years – are ALL about the vagus nerve and polyvagal theory and a bunch of related stuff, that they share as fact (without evidence) on social media (a year or two before they, I predict, will cry that they were gaslighted). Is it a key player?

Finally, why doesn’t Prusty (or 95% of other researchers) intervene in vitro to confirm hypotheses about deficits or abundances? I.e., investigate what it takes to resolve a defective metabolic state?

Why, Thomas?

Why?

Nearly everyone took it to mean the same thing as you did, so not your fault. I too did I must confess. But after his first conference and when everyone was mad at Prusty for under-delivering that I realized, oh, it was our fault for misinterpreting biomarker as unique & diagnostic. (It still may become that, fingers crossed, if it’s validated and tested against similar fatigue causing illness The fact its levels correlate with severity is a good sign). I agree, questionnaires is just not going to cut it. We desperately need a test.

Thanks for the diagnostic biomarker link – I was unaware of most of those.

Perusing that list made me aware of how detached from reality ME/CFS research is – conducted by people who are trying to get rich by patenting tech, or who don’t understand that $$$ esoteric machines with cottage-size footprints and laborious protocols will not trickle down to local labs for standardized use.

It also served to remind me that Ron Davis has been holding the nano-needle technology hostage for about 5 years: he had the world’s best engineer working on it, it was going to cost pennies, it would revolutionize research. It appears to be silo-ed along with the blood flow meter (that would also cost pennies) and the treatments he would discover through robotic testing of genetically modified yeast.

agreed. I look for protocols that have a good explanation behind them and are not monetarily focused. Something like the dry fasting scorch protocol for long covid.

Yes, a biomarker doesn’t have to be unique for ME/CFS, especially since basically all other existing or relevant diseases already have biomarkers.

However, there’s not a dozen biomarkers for ME/CFS. A biomarker has to be reproducable and distinguish two groups with a high accuracy. Almost none of the things on the ME-Pedia were able to be reproduced, in fact in many cases results even contradicted each other. The only thing I would actually consider a biomarker is a multiday CPET. However, since it can be very harmful it isn’t useful apart from studies.

Regarding the most famous biomarker, the nanoneedle, I’m not sure how much it’s worth. I know there’s the whole debate about Rahim not being able to work on it due to NIH funding and tenure etc. However, if the OMF were to hold in their hand a reliable biomarker, then this would have to be the priority above all other things and all efforts would have to go towards the nanoneedle, especially since they are currently running projects that are looking for biomarkers. So I expect it to be less accurate or less useful than some make it out to be. After all the results were never reproduced and it was a very small sample size.

The comments here by Prusty https://twitter.com/cjmaddison/status/1655900703884230657 shocked me a bit to be honest. The whole “you need to decide” if it’s a biomarker. That’s not how biomarkers work, they are not subjective. So let’s see what his paper will entail, can’t wait for the reviewers hopefully to agree to review.

This seems very interesting, although I couldn’t really read or understand it all.

I only wanted to comment that my experience of ME wasn’t a sudden onset. But rather has definitely been more of a long slow burn. With some remissions during periods of rest and not working. Every time I returned to working I made myself worse with more severe symptoms.

Sounds stupid now. But when your doctor and society make you feel like there is nothing really wrong with you – you convince yourself of this too. And keep pushing on and on while fighting against more and more symptoms.

Started feeling ill around 1990. Deteriorated into Severe ish ME in 2014. And still struggling to improve from this now – even though I’m not working at all anymore. Hardly managing to to much at all.

But I do think this “long slow burn” is much more common than you realise.

I don’t doubt that it happens. I’ve heard of people who finally came down with their “final” case of ME/CFS after a series of colds, each of which knocked them lower and lower until they were finally knocked out of the workplace. Many people with ME/CFS or long COVID got sick, tried to keep working and kept getting sicker and sicker.

Comparing the “long slow burn” of ME/CFS compared to the sudden onset of long COVID, though, misses the many people with ME/CFS who had sudden and abrupt onsets. Lenny Jason’s infectious mononucleosis and the Dubbo studies, after all, focused on people who came down ME/CFS after an infection. It’s not accurate to characterize the disease one way or the other. It includes both.

Thanks again for this piece, Cort, you tamed this beast, as you called it.

🙂 I don’t know who tamed who actually but at least it’s done and hopefully it’s mostly correct.

Didn’t another group already look into fibronectin as a bio marker last year? https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35563870/#:~:text=Fibronectin%20is%20a%20potential%20biomarker,%3B%20intensive%20care%3B%20mortality%20prediction.

Interesting. High fibronectin levels were also found in fibromyalgia about 20 years ago. The authors proposed that people with FM had a “non immunological vascular injury”

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11201985/

That’s why he said, ” Knowingly I did not use the word ‘Novel Biomarker’ as a lot is known about it.” Indicating it is well researched, just not in ME/CFS & Long Covid. This is a good thing as it gets us to the end point faster. It sure sounds like a good marker in ME/CFS and maybe Covid!

Hi Cort, I experienced a two year long slow burning phase of me/cfs with multiple “flu like”episodes caused by intense exercise, followed by almost complete remission, before definitively falling down to the most severe one and never recovering.

Awesome summary Cort! Something that wasn’t clear to is whether the IgM against Fibronectin is against plasma Fibronectin or against cellular Fibronectin or against the combination? Should we just guess that it’s against the combination?

Prusty is not a pathologist but a molecular virologist, and if I remember correctly has been a longstanding HHV6 researcher before getting into the field of ME/CFS. You may want to correct that in the gist box. He just had access to a few postmortem samples from Cambridge Brainbank.

What’s with the comment section today, why is it so broad? Is that new? I don’t think I like this. I find having to move eyes left and reight over the whole breadth of the page more energy consuming.

Right – thanks 🙂

Once again, just a big Thank you, Cort.

So grateful for all that you do to keep this community up to date with the latest that is going on in research.

I think that this abstract from Prusty’s 2022 study puts the new work in a context that shows how important it is.

Francesca Kasimir 1, Danny Toomey 2, Zheng Liu 1, Agnes C Kaiping 1, Maria Eugenia Ariza 3, Bhupesh K Prusty 1

Affiliations expand

PMID: 36589231 PMCID: PMC9795011 DOI: 10.3389/fmolb.2022.1044964

Free PMC article

Abstract

First exposure to various human herpesviruses (HHVs) including HHV-6, HCMV and EBV does not cause a life-threatening disease. In fact, most individuals are frequently unaware of their first exposure to such pathogens. These herpesviruses acquire lifelong latency in the human body where they show minimal genomic activity required for their survival. We hypothesized that it is not the latency itself but a timely, regionally restricted viral reactivation in a sub-set of host cells that plays a key role in disease development. HHV-6 (HHV-6A and HHV-6B) and HHV-7 are unique HHVs that acquire latency by integration of the viral genome into sub-telomeric region of human chromosomes. HHV-6 reactivation has been linked to Alzheimer’s Disease, Chronic Fatigue Syndrome, and many other diseases. However, lack of viral activity in commonly tested biological materials including blood or serum strongly suggests tissue specific localization of active HHV-6 genome. Here in this paper, we attempted to analyze active HHV-6 transcripts in postmortem tissue biopsies from a small cohort of ME/CFS patients and matched controls by fluorescence in situ hybridization using a probe against HHV-6 microRNA (miRNA), miR-aU14. Our results show abundant viral miRNA in various regions of the human brain and associated neuronal tissues including the spinal cord that is only detected in ME/CFS patients and not in controls. Our findings provide evidence of tissue-specific active HHV-6 and EBV infection in ME/CFS, which along with recent work demonstrating a possible relationship between herpesvirus infection and ME/CFS, provide grounds for renewed discussion on the role of herpesviruses in ME/CFS.

Thanks Betty, that’s really interesting to read and I’m excited by the Prusty team’s findings. Does anyone know if there are things we can do to help get latent viruses out of tissues safely? FIR sauna blankets come to mind as an idea but no idea if they’re capable of that!

Aciclovir is not the first choice against it because there are other drugs that are more effective against HHV6 but it has actuallly good enough activity against HHV6 and less severe side effects. I could try it once and it stopped my ME brain inflammations immediately.

The thing is, if you don’t want to become dependent on it – it is liver toxic – you’d still want to learn to pace and make adjustments to your work situation and lifestyle. But actually I believe that at least for one group of ME patients there would be this drug but because of a lack of expensive studies everyone believes that there is no therapy. (It is actually not a therapy, but I think that these day MDs belive they have a therapy when they can suppress symptoms : ) – haha.

I suppose that they gave up on Aciclovir too quickly because it can’t help people to get better who are moderately to severely affected. It is a herpes antiviral and it can of course not fix damaged blood vessels and mitochondria and brain tissues. But it can very effectively stop the acute highly inflammatory states of the illness (the flu like thing) : )

Thanks Cort for this detailed explanation of Prusty’s hypothesis. It’s quite a complex study. Let’s hope that after his publication there will be attention for his findings. As I see it, this will not lead to a biomarker. Prusty blew too high off the tower. I am once again disappointed. Although he has provided more insight into the puzzle. About the onset of ME, I totally agree with you that this can be gradually. There are also multiple triggers, all of which makes it difficult to get statistically significant results. Personally, I think there are subgroups for which something has already been found, but which is overlooked. Confirming a result will therefore be very difficult in CFS.

let’s hope Nath has better results. Although I don’t expect much from it either -:)

I really like that researchers are collaborating in the ME/CFS field. I think Prusty mentioned that Akemi Iwasaki reviewed their work shortly before the TLC interview, and he is also in a joint project with Carmen Scheibenbogen to research immune mechanisms in ME (IMMME https://cfc.charite.de/forschung/immme/team/ ) where he focusses on the effect of autoantibodies on mitochondrial function https://cfc.charite.de/forschung/immme/mitochondriale_dysfunktion/.

It was also nice seeing photos of so many top ME/CFS researchers socialising during the London conference on Janet Dafoe’s twitter including Prusty next to Ron Davis and others, or Prusty in a panel with Nath and others, so I think it’s encouraging that all these researchers are aware of each other’s results and increasingly putting the puzzle together.

Academics can be a lot of elbows I’ve heard, so it’s nice to have a research community who really wants to find the pathomechanism and has a spirit of collaboration.

I agree! This is the way science should be practiced! Too often it is not.

This is one of the things I really liked. He’s working with Williams/Ariza whose finding I don’t think have gotten the appreciation they could. I really, really liked it that he’s submitting his results and talking with experts like Akiko Iwasaki and Tim Henrich outside the ME/CFS field and getting their recommendations. I believe Henrich is chasing down some of Prusty’s leads – that’s what we really need.

I wonder if triggering autophagy would be helpful while we wait for treatment ideas. I’m 4 months into an 8 hour eating window plus one 40 hour fast weekly. I’m doing my first 3 day fast now. I can’t tell yet if improvements are real and stable.

check out the scorch protocol autophagy for LC and Lymes

Use of Immune Stimulants to Prevent Viral Reactivation

https://hhv-6foundation.org/clinicians/immune-stimulants

Most HHV-6 reactivation occurs in patients who are immunosuppressed, such as those undergoing stem cell transplantation or who have a genetic immune deficiency. In addition, some individuals may unknowingly become immunosuppressed in response to environmental or biochemical factors such as increased stress. Certain drugs and environmental toxins can activate HHV-6 virus, and several conditions involving extreme drug hypersensitivity reaction are accompanied by HHV-6 viremia (See HHV-6 & Drug Hypersensitivity.) Furthermore, once reactivated, HHV-6A and HHV-6B (as well as several other herpesviruses) can enhance this state of immunosuppression, leading to more rapid development of virus-related symptoms, persistent infection, and increased risk of reactivation and co-infection with other pathogens (See HHV-6 & Immune Suppression).

Thanks for this summary on the herpesviruses. It sounds just like the description of the backend of my frontside symptoms. Yes, with every reinflammation my immune response against it becomes a bit weaker. Also the abstract on the small post-mortem study that you mentioned above is spot on to explain my health problems.

I have learned an excellent health management with pacing over the last year and didn’t provoke a flare-up anymore in almost six months. Still, I’ll come back to read about what I could do from a western medicine immunological perspective. Meditation and acupuncture treatment by a Chinese doctor are the foundation of my wellness and recovery. Western style medicine has become my alternative medicine : )

From my first ME/CFS episode and several years before I learned about ME/CFS I was sure I had a new form of herpes reactivation. I had simplex 1 flare ups since kindergarten. And this was so similar how it always broke out after having passed a deadline and in similar situations where I could relax after a lot of pressure. (Also my ME-brain inflammations get stopped with Aciclovir).

Are there any places in the US where Prusty’s suggested treatment strategies are available? I.e., immunoadsorption, apheresis, plasma B-cell therapy, bone marrow-derived cell transfusion, recombinant B-cell therapy, or natural IgM-enriched IVIG?

Can you clarify this paragraph please? I’m unsure how worried we should be. Is his lab close to shutting down, for lack of funding? Or doing fine, but in need of a bigger building?

“Prusty said the next phase for him is not jumping into more study but, citing the lack of manpower, professional stability, lack of lab space, etc. in his current digs, he’s looking for a new home for his lab.”

Much appreciated work as always, Cort. 🙂

Maybe Cort knows more? But I wouldn’t speculate too much about it at this stage, it might be internal university matters. Prusty in general seems savvy to me in acquiring external funding, based on his past history of grants.

This is the first line of research that I’ve actually been excited about. The capabilities of what these viruses (in herpes family) can do are endless. Go Prusty!

I have moderate to severe me/cfs. My IgM immunoglobulin is low at around 2.6. I’ve often think this may have some significance. Good to hear about IgM enriched IVIg. Sugn me up.

Good job translating Cort! I could only get through the first 15 min the first try. Thanks as always for bringing us hopeful news.

Hi Cort, thanks so much for your blog article and the link to the interview with Bhupesh Prusty. I am slowly trying to understand and processing and hope I can write a comment in the next or weeks.

Thus far, I could find a mistake in your summary. You write that “As interesting as those factors were, Prusty didn’t dwell on them. Instead, he focused on an IgM autoantibody called fibronectin that was low in ME/CFS and which he said correlated well with the severity of the disease; i.e. the more severe the patients, the higher the fibronectin levels.”

Actually it’s just the opposite. Fibronectin levels go down with severity of illness.

It is on page 7 of the transscript that is provided of the interview in TLC sessions nr. 58:

“Fibronectin 1 is one of the most significantly decreased within these immune complexes. So we focus more on fibronectin. Why it is very important because we know from the past literature that fibronectin is a protein which is incorporated into the complement complex, it binds to several antigens and also it binds to C1 and C3 complement proteins and participate in the complement activation process, which basically is required to fight against several infections, particularly bacterial infection. As well as viral infections like HIV and things like that. That’s why we focused on fibronectin one, and it was very interesting because the fibronectin was actually decreased within the immune

complex, suggesting that probably ME CFS patients have a compromised complement activation process, which can allow opportunistic infections as well as viral infections.”

Oh, I see, it is higher and lower in different places. I’ll finish trying to understand the whole thing now!

Yes, I got the correlation mixed up. Thanks for your close reading and letting me know. I just fixed it.