Geoff’s Narrations

The GIST

The Blog

The GIST is in the lower right-hand corner

Wust asked what an intense aerobic workout would do to the muscles in ME/CFS.

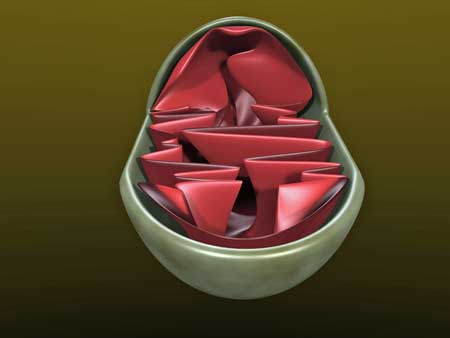

The chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) and fibromyalgia fields have produced some good muscle studies, but a recent study, “Muscle abnormalities worsen after post-exertional malaise in long COVID,” was something else indeed. The study leader, Rob Wust, has a double doctorate in muscle physiology and has been particularly interested in exercise intolerance, mitochondrial bio-energetics, and muscle metabolism.

Thus far, Wust has published three papers on muscle abnormalities in long-COVID patients. The first study of ICU COVID-19 patients found muscle fiber atrophy, metabolic alterations, and immune cell infiltration.

It was the second study, though, that really opened some eyes. This study—which was funded by a variety of sources, including the Patient-Led Research Collaborative for Long COVID and the Solve M.E.’s 2022 Ramsay Grant Program—did something simple but brilliant: it took muscle biopsies from long-COVID patients, put the patients on a bike and exercised them to exhaustion, and then took a second round of muscle biopsies, and dug into them.

The Results

The cardiopulmonary results were pretty typical – a reduction in energy production (VO2 max, peak power output), altered breathing patterns (possibly hyperventilation), plus the near-infrared spectroscopy readings found a reduction in “peripheral O2 extraction”; i.e. oxygen (read energy) was not being taken up by the muscles in normal amounts.

And how about those muscles? What happens to muscles when they’ve been worked hard but haven’t gotten normal amounts of oxygen (energy)? It turned out that a lot happened. The most obvious explanation – low levels of blood vessels feeding the muscles – didn’t pan out, as the ME/CFS patients had plenty of blood vessels (capillaries) feeding their muscles.

That suggested that the problems lay in the muscles themselves. Indeed, higher levels of glycolytic, type II muscle fibers that provide short bursts of energy but stink at endurance in the longCOVID patients provided one reason for their poor performance on the bicycle. Lower levels of an enzyme called succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) that activates the mitochondria provided another reason mitochondrial energy (ATP) production fell short.

Wust – like past ME/CFS studies – found that the long-COVID patients relied more on glycolytic or anaerobic energy production than normal.

Increased levels of metabolites associated with anaerobic energy production and a dearth of metabolites associated with aerobic energy production also suggested that the powerful aerobic energy production pathway had been silenced. The anaerobic rout continued with reduced ratios of citric acid (mitochondria) to lactate (result of glycolysis/anaerobic energy production) levels.

Again and again, the study found that during exercise, the long-COVID patients relied more on the primitive, inefficient, and ultimately toxic form of anaerobic energy production. That’s primitive, as in this form of energy production evolved before oxygen showed up in our atmosphere. We keep it around because it produces short bursts of energy. Anything longer than that and it runs out of gas and starts producing toxic metabolites like lactate.

The list went on – lower creatine levels, problems with lipid synthesis, high levels of oxidative stress, high levels of atrophied or dead muscle fibers with evidence of immune invasion – indicating the immune system may have attacked the muscles.

“It’s really confirming that there is something inside the body going wrong with the disease. It damages your muscles, it worsens your metabolism, and it can explain why you feel muscle pain and fatigue up to weeks after the exercise,”

All in all, the paper provided a gripping explanation from the perspective of the muscles of why physical exercise is so problematic in ME/CFS. As such, it HAD to be rebutted – and it was – but that’s for later in the blog. Next came the exposition paper that attempted to put the pieces together.

The Exposition Paper

In December 2024, Braeden Charlton, Rob Wust, and colleagues published a paper, titled “Skeletal muscle adaptations and post-exertional malaise in long COVID,” that explains what they think has happened to the muscles of long-COVID patients, and probably people with ME/CFS. They listed five possibilities (and rejected one).

Deconditioning – There is no doubt that in the more severely ill, deconditioning adds an exacerbating factor, but the authors noted there is no evidence that it’s causing the illness. (See “the Reply to the Reply” below for more on this).

Hypoxia refers to low oxygen levels. If the oxygen isn’t getting to the cells, they’ll turn to alternative means of producing energy: glycolysis and anaerobic energy production, which studies show is happening in these diseases. Note that ample amounts of oxygen are present in the blood but are not, in a subset of patients, being taken up in the muscles.

Mitochondrial problems could explain the reduced energy production found.

The bigger question is, “What is causing this?” The authors proposed mitochondrial problems that prevent oxygen from being taken up; problems diffusing oxygen into the muscles from the capillaries, caused by capillary blockage; a thickened extracellular matrix that surrounds the capillaries that prevents oxygen from getting out; or amyloid clots that are causing endothelial damage.

Autoimmunity and “Electrophysiological alterations” – It’s possible that β-adrenergic receptors (β2-ARs) could impair blood flows and impact the mitochondria. Allied with this idea is the possibility that increased muscle sodium content (which has nothing to do with diet) may be eating up ATP and causing intracellular calcium overloads, which further smack the mitochondria. (A blog on this is coming up.)

Central fatigue – where the brain turns off muscle activity is another, more distant, possibility.

The problem with the low oxygen uptakes lies between the arteries and the muscles, leaving, if I have it right, two basic targets – the mitochondria and the blood vessels.

An ME/CFS Interlude

Systrom’s invasive exercise studies found that the exertion problems in long COVID are nearly identical to those in ME/CFS. His studies suggest that blood may be shunted from the arteries into the veins before it reaches the muscles in some patients. In other patients, the veins are not constricting enough to deliver normal amounts of blood to the heart – preventing it from pumping enough blood to the muscles. Systrom also has uncovered evidence suggesting that the enzymes needed to power the aerobic energy production process may be inhibited.

Perhaps because they haven’t been studied in long COVID but have in ME/CFS, Wust et al. didn’t mention low blood volume, or the failure of ME/CFS patients to respond on a molecular level (gene expression, epigenetics, metabolomics, proteomics) during and after exercise.

While low blood volume does not appear to be a major factor, it is a factor. Systrom has found that adding saline IVs does improve energy production. A case report from Workwell found that regular use of saline IVs substantially improved one patient’s functioning.

Likewise, hyperventilation (rapid, deep breathing) found in some long-COVID and ME/CFS patients could activate the sympathetic nervous system which, by narrowing the blood vessels, could reduce blood flows to the muscles.

Affirmation

Wust’s “Muscle abnormalities worsen after post-exertional malaise in long COVID” study produced a stunning affirmation of ME/CFS and long-COVID patients’ experiences with intense exercise.

Exercise studies have played a key role in explaining these diseases.

From the beginning of my ME/CFS as a young man, it’s been the post-exertional malaise that stood out for me. While the day-to-day fatigue and pain kept me from functioning like I used to, my symptoms were kind of general and hard to explain. I was very, very tired, I was in pain, I felt like lying down much of the time, I had trouble concentrating, wasn’t sleeping well, etc.

Because these were symptoms that everyone experienced from time to time but were magnified greatly, they weren’t much to bite onto. It was a different story when I exercised, though.

Exercise had been an important part of my life, but now exercise produced an explosion of symptoms, some of which I’d never encountered before. Along with the increased fatigue and pain, came the heart pounding, the intense burning muscle pain, the feeling of contracted muscles, a weird sensation of thickened skin, dizziness, irritability, etc..Those symptoms really stood out.

From the beginning, I thought exercise studies would play a key role in explaining ME/CFS, and over time, through the work of Workwell, Systrom, Keller, Vermeulen, Cook, Hanson, Newton and others, they have been. The good news is that the Dutch team’s muscle findings (reduced aerobic energy production, increased reliance on anaerobic energy production, and others) in long COVID are in line with that past work.

Last Gasp of the Biopsychosocial Crowd?

However, they were a bridge too far for Bridget Ranque and 16 other researchers, who attempted to dismiss the study findings in “Reply: Muscle abnormalities in Long COVID.”

The study finding that very intense exercise harms the muscles does not mean that less intense forms of exercise will necessarily do the same. (Image from Gerald_Altman_Pixabay)

The authors did have one legitimate concern: their worry that long-COVID patients will misinterpret the findings and conclude that any exercise will harm them. As Wust noted, his study needs to be taken in context: it exposed long-COVID patients to a short but very intense exercise session that is literally designed to drive them into a state of muscular exhaustion. I remember during a similar exercise study my legs literally stopped moving the pedals. I have never engaged in that kind of exercise outside of an exercise study.

The GIST

- The ME/CFS and fibromyalgia fields have produced some good muscle studies, but a recent study, “Muscle abnormalities worsen after post-exertional malaise in long COVID,” was something else indeed.

- The study found that aerobic energy production – the kind that relies on oxygen uptake – was inhibited in various ways. Higher levels of glycolytic, type II muscle fibers. lower levels of an enzyme called succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) that activates the mitochondria, increased levels of metabolites associated with anaerobic energy production, and reduced ratios of citric acid (mitochondria) to lactate (result of glycolysis/anaerobic energy production) levels all pointed to an energy production system that was overly dependent on the primitive and inefficient anaerobic energy production system.

- High levels of oxidative stress, atrophied or dead muscle fibers, and signs of immune invasion suggested that the short but very intense period of exercise had directly damaged the muscles.

- In 2024, the authors published a paper proposing 5 possible explanations for muscle problems found in long-COVID patients.

- After rejecting deconditioning, they concluded that low oxygen uptake to the muscles caused by mitochondrial problems and/or reduced blood flows to the muscle cells, an autoimmune reaction that impairs both blood flows to the muscles and/or mitochondrial activity, and/or problems originating in the brain (central fatigue) were likely impacting the muscles.

- ME/CFS studies suggest something similar is happening and add in additional factors such as low blood volume, hyperventilation, and the failure of ME/CFS patients to respond appropriately on a molecular level (gene expression, epigenetics, metabolomics, proteomics) to exercise.

- Recently, 16 researchers, many of whom are allied with the biopsychosocial field, attempted to dismiss Wust’s findings in a “Reply” to the study. They asserted that deconditioning produced the findings, that the symptom exacerbation seen in the ME/CFS patients was a normal response to exercise, and that the patient’s pathological response to their symptoms played a role.

- Wust showed that the ME/CFS patients had activity levels similar to the controls—and to the average American—that the symptoms produced were not normal, that numerous findings of the study were either not associated or, indeed, were opposite to those found in deconditioning.

- The biopsychosocialists arguments seem to be becoming ever more shrill and less convincing. For instance, Beatrice Ranque, the lead author of the reply, concluded that because normal physical examinations and routine test results suggest that “no organic impairment” exists in long COVID, psychological factors must be important.

- Meanwhile, at least five more muscle studies are underway in ME/CFS and long COVID-19, and a recently published invasive exercise study provided more insights into the pathophysiology of long COVID-19. A blog on that is coming up.

Workwell’s post-exercise symptom assessment of patients after their two-day exercise test for disability indicated ME/CFS patients who are in good enough shape to take the test invariably recover within a period of time. When David Systrom’s patients reach a certain level, he recommends his patients start an exercise regimen. Similarly, Health Rising recently ran a recovery story where Lucinda Bateman instituted an exercise regimen using sit-ups and low weights in a patient when he reached a certain level. I stayed away from weights for decades but now find that using exercise bands in short bursts is helpful. D. Hupin, one of the co-authors, found that personalized strength and endurance training, which did not result in PEM, was helpful in long COVID.

In his “Reply: Muscle abnormalities in Long COVID” Wust so easily wiped away the rest of their concerns as to make their “reply” seem like it was borne out of desperation.

Deconditioning? It was like déjà vu all over again (:)) when the authors trotted out the old and tired deconditioning trope. Because the patients were deconditioned, the authors asserted, the short but intense exercise regimen was going to produce muscle damage.

Wust pointed out that the long-COVID patients exhibited the same activity level as the healthy controls (5,181 vs. 4,727 steps/day for patients and controls, respectively) – about the same activity level (rather sadly) as the average person in the U.S.

Several physiological findings demonstrated that something different from deconditioning was at work: the different skeletal muscle alterations, the opposite mitochondrial substrate utilization (more carbohydrates), and the abnormal muscle findings found before the exercise intervention. The significantly lower gas exchange thresholds and respiratory compensation points indicated that effort was not a problem.

If Wust had included findings from ME/CFS, he could have added more objections. The deconditioning hypothesis originally turned on the fact that low stroke volumes were found in ME/CFS. Still, Van Campen et al. found that everyone with ME/CFS -whether they were bedbound or active – had similarly low stroke volumes, indicating that while low stroke volumes are part of the disease, they are not the result of being inactive.

Since everyone experiences muscle pain after exercise, what’s the big deal about muscle pain in the ME/CFS patients? Seeing this objection come out of the pens of some long-time ME/CFS researchers – who well know that PEM produces many other symptoms – was kind of sad.

The patients’ experience of their symptoms caused their distress. The authors used the Nath ME/CFS intramural study to conclude that the patients’ “experience of symptoms” and altered interoception, allostatic load, and perceived burden explained their response.

Wust pointed out, though, that the Nath paper did not explore any of those topics and, in fact, provided “multiple physiological explanations for ME/CFS pathophysiology, including autonomic dysfunction, differential cerebrospinal fluid catecholamines, and metabolite profiles, and lower post-exercise cortisol responses”. Plus, it confirmed Wust’s findings of lower °𝑉𝑂2max and impairments in skeletal muscle mitochondrial metabolism”.

“Ranque” Desperation?

The biopsychosocialists are still out there, but seem to be more of a fringe element, and their arguments seem to be becoming ever more shrill and less convincing. Take Beatrice Ranque, the lead author of the reply to Wust. In “Why the hypothesis of psychological mechanisms in long COVID is worth considering,” she fell back on the weak argument that because normal physical examinations and routine test results suggest that “no organic impairment” exists in long COVID, psychological factors must be important.

She hit that theme again when she pointed out that “self-reported persistent symptoms poorly correlate with objective long-term organ damage”, and when she wrote because “debilitating and persistent symptoms…are not fully explained by damage of the organs“, therapeutic interventions should follow those recommended for “functional somatic disorders”. Her conclusions – which completely ignored the molecular findings in long COVID – were embarrassing in a disease as new and poorly studied as long COVID.

It’s no wonder, though, that Ranque was so bothered by a study that found plenty of “organic impairment”. With objections like Ranque et al.’s to the Appleman/Wust long-COVID study, people with long COVID and ME/CFS have little to worry about – and indeed, with a mess of ME/CFS and long-COVID muscle studies coming up, things are probably not going to get any easier for them.

More muscle studies are underway.

Upcoming Muscle Studies

Two major ME/CFS muscle studies funded by the Open Medicine Foundation are underway. One will take a deep, deep dive (genomics, proteomics, metabolomics, phospho-proteomics, ultrastructural analysis, mitobiogenetic markers) into muscle samples from ME/CFS patients. The other will take muscle samples before and after a two-day CPET exercise test and, among other things, assess levels of citrate synthase (which Systrom has found depleted in ME/CFS before), gene expression, metabolites, and proteins in the muscles.

Plus, Paul Hwang of NHLBI and Avindra Nath are continuing to collaborate on their WASF3 muscle cell findings. Rob Wust’s Solve M.E. Ramsay award examines muscle biopsies before and after exercise in ME/CFS, and David Cosgrove at Cornell scored an NIH grant to analyze ME/CFS muscle biopsies using new technologies to “identify changes in cell-cell communication (ligand-receptor) pathways involving myogenic, endothelial, and immune cells and their spatial organization between control and ME/CFS muscles” and assess the role blood vessels play.

Things are moving quickly. Last November, Leitner and Singh took invasive exercise testing to a new level in long COVID. A blog on that study is coming up.

Thanks as usual Cort, this is all very interesting. I really wish though that once again authors would make comparisons between long COVID and fibromyalgia and not just ME/CFS and long COVID. Do you have any information on whether similar data have been found in FM? As you note, that would have even further strengthened the argument in the reply to the editorial authors trying to cast doubt on the study results. It seems to me too that with the strong pain and exercise issues also present in FM it only makes sense to include it – is there some reason why these findings would apply more to ME/CFS? I just find it so frustrating that FM is being left behind, in study funding and in application of results from long COVID.

Frank I could not agree more, they definitely need to add fibromyalgia to these tests.

Check out the german start up called “Mitodicure” and Prof. Klaus Wirth.

Couldn’t have said it better. These are my concerns as well.

I feel the same way. Not so long ago we still heard about fibromyalgia in those types of studies, but lately it feels like we have been forgotten, or considered irrelevant.

As I understand it, the main symptom of FM is pain.

Pain is not a universal symptom of ME. The top diagnostic for ME is PEM, whereas gentle and increasing exercise is beneficial to FM sufferers.

Am I wrong? Not sure about LoCo.

Yes, studies indicate FM patients can tolerate exercise much better than many people with ME/CFS. It depends where you are on the continuum. I have more pain and can tolerate exercise better than most. I’m on that part of the continuum.

On the other hand, there are so many similarities in the brain, gut, muscles, metabolomics, small fiber neuropathy, even orthostatic intolerance, and others I am sure. Hard for me not to be believe that they’re not closely related.

I think you are right I have both and I could take walks etc with FM but not with mecfs only causes PEM which I never encountered with FM.

I would have included FM research in there if I’d had the energy :). My sense is that there may have been more research on the mitochondria in fibromyalgia over time than in ME/CFS. This is because of the focus on the muscles. There’s definitely been more muscle study in FM thus far. Here are some blogs

https://www.healthrising.org/blog/2021/05/04/fibromyalgia-muscle-mitochondria/

https://www.healthrising.org/blog/2020/07/27/genetic-mitochondria-fibromyalgia/

https://www.healthrising.org/blog/2017/11/06/metabolomics-study-points-finger-energy-production-fibromyalgia/

While we aren’t getting a lot of FM research some astounding papers have shown up over the past couple of years including findings suggesting something in the serum is causing FM

https://www.healthrising.org/blog/2024/10/19/blood-chronic-fatigue-syndrome-fibromyalgia-long-covid/

https://www.healthrising.org/blog/2023/05/10/immune-disease-neutrophils-fibromyalgia/

You’re not alone though in thinking the FM is not getting its due in long COVID. Dr. Clauw feels the same way and wrote a paper on it.

https://www.healthrising.org/blog/2024/08/31/fibromyalgia-chronic-fatigue-long-covid-central-nervous-system/

FM isn’t getting the buzz that ME/CFS is right now (not that ME/CFS studies are jumping off the charts) but I think that over time, as the work on long COVID proceeds, it will get it.

Brilliant! Thanks for the reporting.

Just commenting to point out two confusing typos that may need fixing?

“Plus, two hallmarks of deconditioning – decreased filling pressures and reduced peak CO2 – are opposite to those found in deconditioning.” Deconditioning opposite to deconditioning? I think one of those is meant to be long-COVID/ME

“Plus, ‘The significantly lower gas exchange thresholds and respiratory compensation points’ indicated that the reduction in aerobic functioning found was not effort-independent.” – Do you mean not effort-dependent? Sounds like you’re saying those effects were dependent on effort by saying they’re NOT effort-independent.

Again, thanks for this 🙏 good news for the community.

Both fixed! Thanks!

Dr Ranque’s forename is Brigitte and not Beatrice ( I know cause I’m french and she’s one of the important player with a lot of institutional weight here in the long covid/ME-CFS medical community…)

And I for sure hope this kind of study will provok a shift in her belief system , although I doubt it.

What we need is more studies then a critical mass of data then a new medical consensus…

Fingers crossed !

TY for the great summary Cort. Any new abnormal findings can potentially provide missing pieces of the puzzle, so I applaud this researcher’s initiative and findings.

However, the dogmatic escalating commitment of a dwindling pocket of other “researchers” to the psychological dismissals of patients and their complaints helps no-one (aside from giving doctors license to excuse themselves from doing deeper investigations into possible underlying physiological causes of our symptoms). However, an easy dismissal of a complex/unknown problem can be a powerful incentive for a busy doctor – who has a never ending line of “lower hanging fruit” waiting at the door.

Incidentally, “escalating commitment” is a known psychological phenomenon whereby once an individual makes an (even slight) commitment to one side of an argument, their commitment to their chosen position will often escalate when challenged (even by facts), probably due to a desire to “save face”. If the “Psychosomatic Dismissers” are so bent on blaming the disease on psychological phenomenon – even in the face of mounting physiological scientific evidence to the contrary – then perhaps they would also be open to accepting that their refusal to accept contrary scientific evidence is also (or instead) a psychological phenomenon (due to escalating commitment)?

Does this sound familiar?; “Since I don’t personally know the cause of your symptoms or disease, it must all be in your head (and implicitly – therefore I won’t waste my time looking any further)”. I have always considered this “all-too-handy/common” presumption by Clinicians to be a combination of ignorance and arrogance that is beyond the pale. It is enough to make a desperate patient scream, cry, or (eventually) just give up consulting doctors/whipping a dead horse.

Thus, I am disheartened when anyone considered to be a “researcher” pays any credence to psychosomatic dismissals. Even if there might be some small partial truth in theories that “some patients’ perspectives or coping strategies may act to exacerbate their symptoms”, promoting it as if it was the only or core root cause (while rejecting scientific evidence to the contrary) will only act to reduce the call and funding for real research, and the onus upon Clinicians to take these diseases (long Covid, CFS and Fibro) seriously.

This is just my take, based on 30 years of seeing innumerable Clinicians/Specialists – some of which were likely highly skilled in their fields – but whose skills were (by and large) “rendered useless” by their (medical culture pre-programmed) psychosomatic dismissals, simply because standard cursory lab screens for (other) common known diseases showed/show nothing definitive. If anyone’s thinking is irrational or unsound here, IMO, it is not the perpetually dismissed and frustrated patients’.

OMG! Yes!! This is exactly the state of affairs and a perfect description of the psychological state of way too many Drs! Especially those working for the VA but I periodically run into others. They want to get paid the big bucks but aren’t putting in any effort to keep up with changes. My favorite example (not in VA) was a highly regarded allergist at a big hospital that told me that “Allergists don’t think MCAS is a thing”. That is like the most stupid thing ever said. What he should have said was, “I’m sorry, this is outside my expertise and I’d rather just do allergy testing and give people shots.” At least I wouldn’t be spreading the word locally to avoid this guy! Hope you don’t mind if I semi-plagiarize this and hand it to the idiot Drs I run into on a too frequent basis. I’ll never see them again and who knows, it might wake one of them up to know what their patients really think of them. 🙂 Thanks!!

Thanks, I appreciate the effort to inform doctors your not the only one sick. I always mention others and young people have these very difficult to live with illnesses. I say, Doctor people with depression don’t want to get off the couch, if they forced themselves to walk a couple of miles they would feel better in a few days. People with CFS,ME,LING,FM are pissedoff that they cannot get off the couch, just standing up can cause you to feel taxed. If they forced themselves to walk a mile, you might find them lying in the street unable to make it back, screaming with spasms, frustrated, crying, unable to find words to discribe how they feel, foggy, look like they are under the influence,and in a much worse condition after. Days not hours to recover. (I really miss the positive feeling after positive exercise)Not one positive effect from the walk.

20 yrs, I have yet to rip one into a new one.

This will be my last post here.

Frankly, I am sick of all the talk and going round in circles in research. Gosh, we’ve had all sorts of theories over the years – HPA dysfunction and TH1/TH2 in the early 2000s, a retrovirus got thrown in that got us all briefly excited, rituximab excited us then flopped, neuroinflammation got me excited for a few years until I realised recently it was another interesting theory going nowhere….

I have had an albeit mild form of this illness for nearly 35 years. What pains me much more, however, is the suffering of my 17 year old daughter over the past two years.

I am sick of the broken promises , of the trials that seemed to promise so much but never started, or started and failed.

I think there’s a good number of charlatans in me/CFS circles, unfortunately.

My son is 26. He is me/cfs free. He’s never had the condition and I hope like anything he never does..

I never imagined, in 1990, that I might have a 17 year old daughter with me/CFS in 2025, and there’s STILL no treatment. Not even treatment that can help, let alone cure.

So….. maybe the illness IS psychosomatic. Or perhaps, more likely, so complex that it will always defy modern science.

In the meantime, I hope and pray that my daughter will heal, in time. After all, I got significantly better over time. Probably 85% of my former health. I have been able to

live a pretty good life

Thank you for your work, Cort. I hope

One day that your persistence will be paid off with some meaningful progress.

Good luck to you all, and God Bless

Sorry you have to go through this but science takes time and progress isn’t linear. It’s a discussion and there will always need to be many theories to find the ones that are actually correct. That’s the scientific method. If you wanna blame anyone for the lack of progress, blame the lack of funding. If we had the ability to actually test all hypothesis thoroughly, we’d likely have been -much-further along years ago.

Thankyou for this interesting discussion and summary of clinical findings about pem. This reflects my personal experience of trying to exercise. I have cfs/me. I recently did a ‘return to exercise’ program with an educated physio who encouraged me to rest and pace whilst doing small amounts of specific exercises. By keeping well within my exercise tolerance and aerobic limit ( which sadly is very low after 18 months in bed or a chair, with infrequent trips out), I found I felt better. And very slowly I could increase my exercise levels. They’re still way below a person without cfs/me however.

As a former judo instructor, I’ve found the loss of energy to be crippling. I’ve tried ‘doing more to get fitter’ and ‘pushing through’ simply made me crash so badly. I’ve had to learn the new boundaries and how to pace effectively. None if it was psychological! Although the side effects of having a life changing illness definitely has a psychological effect. I’m so pleased there is a growing body of evidence to support the experience of so many sufferers and hopefully there will be a solution found in the future. Thankyou so much researchers.

Hi Sue. I was a national judo champion when I was 12 and now have moderate/severe ME aged 36. It is crippling and as you know Judo is a very physically demanding sport. It’s ironic we are both in this situation and can no longer push our bodies as we used to. But I’m glad the science is slowly starting to explain why and why I’ve always experienced such intense problems with muscle pain and fatiguability which means I can barely stand up and walk at times. I’ve gradually declined over the years despite my best efforts and really want some kind of treatment to restore some functionality again.

Sorry to hear the thiamine didn’t help your daughter. It was a long shot. I hope you’ll check in for a quick look periodically as you’ll never hear the news in the lame stream media if a substantial break through (read cure) happens. In the meantime just focus on keeping her spirits up. It’s not psychological but psychology is import to persevering and moving forward when things look bleak. Blessing to you both!

Hi Matthias, whishing you and your daughter all the best. I had a time a couple of years ago, where I felt overwhelmed by the variety of research topics as if there was no clear way forward.

I do not feel this way anymore: To me, much progress appears to happen, and I am writing this just in case it might buoy up your mood to see someone viewing it more positively due to the reasons below.

My current view of ME/CFS existing research is, in short, that ME/CFS is probably a complex cascade dysregulation in the body, of which research has already uncovered many puzzle pieces in the body, but is still looking for the “main switch” (and root of PEM). My bet is also on an epigenetic element to the disease.

What makes me hopeful is that:

a) Results are increasingly being replicated, the same topics start to come up various studies which also shows in the fact that Cort is increasingly able to make connections and crossreferences between studies

b) tRat research technology has made leaps that allow for detailed research that was not possible 10 yrs ago (like Maureen Hanson’s urine metabolome studies, or Prusty inventing his own tech for looking at viral interaction with cells). Only now can we look that closely at some things.

c) That the ME/CFS research community is, in my eyes, remarkable for the fact that they seem to be defined not by elbow competition, but by a spirit of truly wanting to solve ME/CFS and cooperation (take as an example the Stanford Working Group Meetings where international ME/CFS scientists freely share pre-publication results with each other)

d) That only since the Pandemic, ME/CFS started to be officially recognised, and only recently have official guidelines been changed in some countries to no longer treat ME/CFS as a psychological illness (like with the NICE revision in UK, or in 2024 revision of German guideline).

e) That the increased recognition of ME/CFS has been reflected in donations like the foundation who awarded a prestigious medical grant to Akiko Iwasaki, or that crypto tycoon chipping in.

f) The role of viruses also emerging in other fields of research (e.g. MS, dementia research…)

f) Here in Germany, I’ve noticed a lot of change in media reporting: Whereas before the Pandemic, reporting was about zero or wrong, now there’s a steady online media stream of both sympathetic portrayals of patients, including reporting on research, both actually including 95% correct descriptions of the disease. Âlso, since the Pandemic, ME/CFS awareness and allies have been built among politicans of all parties.

So I agree, it will be complex and difficult to solve, and does not yet guarantee a treatment. I am pretty much stuck at severe ME/CFS right now. And there is still much to few research funding. But I truly believe that conditions for solving ME/CFS have never been better than today.

I hope this cheers you up maybe a little. And if you feel like coming back after some time away, I’ve always appreciated your comments!

Kind regards

“that research technology”, not “tRat research technology” 😉

Lovely post, JR. I have to admit that I focused on tRat research technology and thought “That’s new! I wonder what tRat can contribute?

Thank you :-). Haha, I had forgotten about my own typo by now, so at first I saw only your reply and went like: “Oh, interesting – tRat technology, what might that be?” 😀

Well, I am crossing my fingers for the momentum from the pandemic to continue into the future, and of course the US government funded part of research has taken a hit. But I think much of what I wrote above remains true and I can report the good news that ME/CFS and LongCovid research have made it into the new German goverment’s coalition agreement :-). Now if only there would be some kind a billionaires club dedicated to making solving ME/CFS their legacy, that would be handy, with or without “tRat” technology 🙂

Thank you JR

Kudo’s JR! That inspired me!

Look at Germany – I don’t remember ANY ME research coming out of Germany for decades..I mean none! I didn’t even know that Germany did medical research (lol).

And now look – medical conferences, studies, papers….I’m not saying that Germany is overflowing with ME funding but the change has been remarkable and its occurred pretty rapidly.

I think much of those new projects are part of centrally organised joint research projects with many partners, in the planning of which Scheibenbogen was I believe heavily involved.

It’s not all roses etc. though, I think I’ve read she was just recently denied funding from the Ministry of Research for repurposing a very expensive (MS?) medication for which the producer charges a couple of thousand Euros per dose. (I’d be in the mood for starting a petition to the producer, if I had the energy, etc…)

General elections are happening in Germany next weekend, and there will be challenging coalition negotiations as possibly three parties will need to cooperate to form a government. One of them, as well as one likely opposition party, have ME/CFS research and care in their election programmes. I am not sure how much room it will have in otherwise challenging negotiations, but I don’t think the topic is going to go away. Since last year, ME/CFS officially exists in the German public health system 🙂

I’m crossing my fingers that the momentum from the pandemic will not dwindle but be the gift that keeps giving. That’s probably where the challenge lies.

Thanks for the update. Funding is a struggle in the US as well – but at least the struggle is underway in Germany now. Good luck!

Not Matthias! Oh no!

Not the reaction I expected or hoped for from this post.

I wrote it because I feel like it shows that the research field has become more centered on two things—the mitochondria and blood flows. Whether it’s the muscles or the metabolomic or CPET studies those two possibilities keep showing up. Hopefully, they have been validated enough for big studies to really knuckle down on these areas and figure out what’s going on.

That’s my hope – sorry that didn’t come across or if it did it didn’t inspire any hope.

Treatments are more difficult… but I don’t know if you saw it, but Jarred Younger is on the trail of a drug that I’ve never heard of before and that’s the key. I know there are surprises out there and the more eyes we have on ME/CFS, long COVID, FM, etc. the more they will show up.

I sincerely hope we will see you again!

Thanks Cort, I was having a bad day in many ways and it was more of a vent! A therapeutic one I must say

Good to hear! I’ve found that getting stuff off my chest may not be pretty but it often enables me to move on.

Your daughter’s situation is apt. I imagine that many of us oldtimers have made some sort of troubled peace with our situation and we may have forgotten how brutal it was for us when we were young and had to face the losses that this illness imposes.

We should keep them uppermost in our minds as we fight for more help.

(A blog on what we know about young people with long COVID is coming up by the way :))

Cort,

You are right. I do remember very well when it started 35 years ago for me and the state of total panic that I was in with absolutely no clue at all about what I had. At that time, I thought I had caught HIV, cancer, etc, name it, all at once and that I was going to die so I felt bad. After a huge bunch of tests with the same results, all the Drs told me: ” You have nothing. You are just very tired. Rest for a while and everything will get back to normal”. Nope, 35 years later, nothing is back to normal.

I know….I never would have thought 40 years later it’s still here!

“some sort of troubled peace with our situation” – very well put Cort.

I have ME and POTS. I continue to look for an answer but try to be grateful that I’ve had a good life before I got sick. But my 17 yr old daughter also has ME and POTS. She was having some symptoms from previous bouts of Covid but this lady infection in July 2024 made her symptoms explode. You are right: It is so much worse watching your teen/young adult go through this! She needs a chance at life.

I live in the UK and an organisation called Action for M.E. has started a big funded study. We had to fill in a detailed questionnaire first and then some of us were asked to provide DNA samples. It is a very big study with a university involved and it is called DecodeME. Hopefully it will help them come up with some answers for the problem which affects so many and some people and even DOCTORS say it is all in the mind. Wish I could let them feel the pain and the wasted days of our lives recovering.

This is interesting for me to read because I also got my father (I am assuming yu are the father from the name.) He had a mild version but I have a much more serious version.

I am surprised by your frustration because this new research gives me hope. While you have clearly waited a long, long time, and that is incredibly painful, especially because your daughter is involved. But research is moving fast and we’re finally getting committed biological researchers. It’s getting harder and harder to deny, which will help us get more funding and more research.

I know this probably goes without saying, but make sure you support and affirm your daughter. The most important thing my dad did for me was believe me when no one else would.

Matthias, you’re right. They’ve been talking about it for years, and if you go back to, say, 2014 the articles are very similar to today. I’m an LC with ME/CFS (PEM is my major symptom) and I must say, Gupta could be working for me. It helps me to tame my worries around getting symptoms when I do things. There is an analogy, I’m sorry I don’t have a source, but in a book I was reading it mentioned a study that determined chemo patients were getting nauseaous BEFORE their chemo even started for the day. This is a conditioned response from the brain, and I believe it is very similar to our plight. Time will tell. I still take Oxaloacetate (it helps with brain fog) and I’m trialing minocycline. I’m much more active as of late. Something is working.

I’m glad you’re getting better with Gupta – it makes sense to me that tamping down sympathetic nervous system activation could help but I must disagree that the articles are “very similar” to today. Not even close. For one – long COVID wasn’t around. Mitochondrial study was in its infancy – nobody was talking about autophagy, MTOR, complex I deficiencies, substrate utilization problems. We didn’t know that amino acids were being preferentially utilized in ME/CFS. Since we had no invasive exercise studies we didn’t know about problems with oxygen extraction and preload. Nobody knew that muscle repair mechanisms were impaired or that on a molecular level that the body was just not responding to exercise, no one was looking at coagulation.

Honestly, I could go on and on… Oxaloacetate, nicotine patches, guanfacine, Bariticinb, inspiratory breathing, monoclonal antibodies on the treatment end.

I stand corrected, thanks for your response, Cort.

Hi Matthias,

I can imagine the frustration. It seems sooo complicated. I am not sure what to believe anymore. What is like what, why are certain diseases so similar, or are they the same? Are we looking at 30-60 symptoms or are they alle caused by one thing. Its interesting that you are asking if it could be psychosomatic, most people will decline the possibility. I dont have an awnser to that question but I can tell you my experience. I had all symptoms of me/cfs and it turned out somatisation disorder. (Or maybe both, who knows). Its weird to me that somatisation disorder can mimic all the symptoms like that. If you havent seen it yet, check out cfs recovery on youtube to see if you recognize the story. Its about symptoms being explained by a hypersensitive nervous system. Lots of people in the comments improving there.

I wish you lots of strenght and health for you and your daughter.

Hi thank you for writing this.It makes lots of sense to me.I’m diagnosed with fibromyalgia.My symptoms are:-I feel like I’ve been poisoned,been to the gym after not going for a long time and that I’m bruised everywhere.Also I’m always exhausted and have cognitive problems.I have also got sleep problems.Sorry I’m having difficulty writing anymore brain won’t work properly.Thank you very much for helping me try to understand x

Oooo you brave soul. I have fibromyalgia too. 😔 soothing healing energy coming your way. Xo

I forgot to say I feel like I have flu all the time

Feels like we’re going in circles. No major progress towards a treatment. Sparse studies producing only tiny leaps forwards. The underlying cause of the disease still essentially unknown. It realistically seems like we’re 20+ years away from an actual effective treatment that significantly affects our quality of life. I’m 25, have had ME since age 13, and the outlook feels hopeless.

Thankyou to Cort, the researchers, and those who take this devastating disease seriously.

Yes, it is mostly small steps – I guess that’s the way science mostly works: the findings slowly build on each other – but in a way we’re seeing remarkable progress. Take the muscle biopsy studies, though. Wust’s was the first to assess the muscles after exercise and he found a bunch of stuff. In general it validated what we know but it did so at the muscle level – so now we have validation of the turn to anaerobic energy production at several different levels – 2-day CPETs, invasive CPET, metabolomics and probably others.

Now that that question has essentially (I believe :)) been settled the question is where the breakdown is – and the list is not short but it’s not that long either – and that’s where the next research will go. For me, I’m very encouraged by all the muscle studies.

For the past 30 years or so, we’ve had two small teams – working out of the UK and Italy if I remember correctly – working on muscles in ME/CFS. Now we have 2 major muscle studies from the Open Medicine Foundation, two more from the NIH (WASF3/Cosgrove), Wust’s ongoing work, plus Klaus Wirth has come up with a way to explain the extreme debilitation and a new invasive exercise long COVID study just came out.

The difference between where we are now and where we were 2 years ago is just remarkable. Of course, finding a treatment is a different thing we don’t know what future findings will provide in that area – but we are making ground.

I don’t think the difference in the last two tears is ‘remarkable’ at all, but I admire your positivity.

Certainly we have had some new and interesting research.

I was quite positive about Polybio, but now I am not so sure. Amy made a very categorical comment in a LA Times article that I thought was less factual and more propaganda.

I’d really like to know how Amy(polybio) got well. I’ve asked her in the past and all I got was…”there are lots of people on here that recover”)

Only to discover after that she in fact took an “experimental drug” that pulled her out. I’d really like to know what that “drug” was?

Reminds me of my son in laws best friend that is a physician.We were all contemplating getting the covid vax so my son in law says … “I’ll ask my friend the physician if we should get the vax”

Well, we all got the vax. My 3rd vax caused a grapefruit sized lump in my armpit. NEVER AGAIN!

The son in laws friend (physician)got 5 shots (in order to keep his job) and ended up with what the docs told him was idiopathic HLH and dam near died….most people, if not all with HLH do die

I suspect because he was one of them…he got preferential treatment that nobody else gets and pulled completely out and is perfectly well today

I’m afraid we are a group of people that were/are being played by the system.

I believed in the system only because my wife worked at the hospital for 35 years

What researchers don’t get is the system is set up to generate revenue. One look at the USA system and how all the hospitals are being bought up screams corruption.

I’m affraid what will happen in these illnesses will be, a drug will be found to treat the condition just like all the other diseases.A “CURE” will never be found.

Just like cancer, billions will keep being poured in to these “run for the cure”fundraisers

Meanwhile people are using ivermectin and fenbendozole with very good lasting results. Google “cancer” and professor “Thomas Seyfried” at Boston University.

I have a sister in law that has severe MS.She lives on peanuts,barely paying rent ,groceries etc.Meanwhile the MS society rakes in millions and spends very very little of those funds on research or the sick MS people.its all about the $$$$ folks

I just find it mind-boggling that in today’s world with the cutting edge technology we have in front of us in so many other fields, that a cure for almost all diseases hasn’t been found.

If that doesn’t scream corruption in your ear then I feel so very sorry for the hope you were hoping for.

And we all thought the internet was going to accelerate so many cures for diseases.

Comon’ Amy,devulge the drug that pulled you out so we can all access it through the dark black market

Thanks for your response. I’ve just reread my comment and it was unnecessarily terse and pessimistic – apologies for that.

I’d been reading some discussion of me/cfs on forums containing doctors which had thoroughly depressed me. It’s truly painful to see many medical professionals still not taking the disease seriously, dismissing sufferers as lazy/liars/mentally ill. If only they’d take the time to actually read through some of the research.

The work of Klaus Wirth does in fact give me some hope. His theory of me/cfs is certainly compelling.

This site really helps keep me sane. Thanks again.

I wonder about these strange TCD8 “exhausted” find in some studies. How came ? And what do they do now ? They should have deseapered after infection or stress, how can they still be here ?

The whole immunity is not exhausted if it was the case we should not have PEM.

Aren’t they now acting as trigger ? I’d love to see more studies about.

Weird and random but from a place of appreciation and growth mindset….

I wanted to acknowledge your open admitting to a mistake and apology. I haven’t read your previous comment and I shant now. :p

Your wisdom shown in this comment blew me away. I value your (and all others’) courage;

and compassion;

and ability to stand up and say

“I. was. wrong.”. Wowwy!💜

You get the “Being a Great Human” award. 😁🏆 Keep up the wonderful growth and maturity and greatness! 🙂

That blew me away, thankyou. 🙂

The NIH and Open Medicine references in your comment, can you find me the link for those please? 😊 I’m hoping to March into my Dr’s office going “here’s the proof and the specifics of the symptoms”, learn and use that brilliant mind I’m paying for, to come up with something. 😂🙃”

Exactly, well put.

I wouldn’t even guess when we might properly understand this illness or have treatments.

I have got my hopes up far too much in the past

Hi Mark, if you want to have a look, I just left a comment above, summarising some reasons to be hopeful about ME/CFS research. I also feel pretty much stuck right now after 12 years, the last 2 of them severe, but the the points above are what gives me reason to be hopeful.

And as to the research in this blog, I feel it’s actually a pretty big deal that there is tangible scientific evidence for PEM. It wasn’t there 10 yrs ago, making it so easy to psychologize the disease. Now we have tzat more and more from various studies: This graph from Maureen Hanson’s study always cheers me up: https://x.com/DrMaureenHanson/status/1624786614764425216 🙂

Hey, I’ve just read your comment – thanks for writing it. I was having a rough day and it cheered me up a little. Sorry to hear of your situation. There’s so many of us out there living through similar ordeals – it’s somewhat comforting to know I’m not the only one suffering.

Germany really seems to be a leader in producing cfs research and raising awareness for the condition. It’s indeed encouraging to see building evidence of measurable physiological disturbances. Hopefully as time goes on medical professionals will be forced to take our condition more seriously, and not simply dismiss it as ‘psychological’ – as it seems many sadly do.

Hehe, maybe a frequent side effect of ME/CFS is a well-practiced ability of looking at positives 😀

I would not really say though that Germany as a country is where ME/CFS leadership comes from: I think it’s more that we’ve had one dogged little woman (Scheibenbogen) 🙂 who pursued the topic for years with politics since she “inherited” a group of ME/CFS patients at Charité Berlin. And the patient organisations who in my opinion did a splendid job, one of them also filling the role of a Medical Society for ME/CFS (partnering with Scientists like Scheibenbogen as advisory board), and all of them doing a great job representing ME/CFS to and working with politics. It was also patient organisations who successfully intervened with a postcard campaign when a preliminary research report commissioned by the Ministry of Health did not sufficiently represent the dangers of outdated exercise therapy. I think some of the few politicians in various parties who are really sensitised to the topic have been made aware of it in the first place by patients. And there was a successful patient-organised ME/CFS petition to parliament that helped raise awareness. And it was also the Pandemic that made change possible I think.

I’m sorry you had a bad day at that board. Just last week it also put a bit of damper on things when my delivery man showed up full-on sick and declared 1. his GP had said Covid did not exist any more, 2. those Covid tests were not working anyway because these days they just showed positive results at anything which is why he did not test in the first place…Oh well 😀 So I suppose these doctors are still there too. But change is defintely noticeable to me. And in the end, that encounter with the delivery man made me think of the nice English proverb that “Denial is not a river in Egypt”, and how that often applies to my pacing skills (or rather lack thereof..) too – so who knows, something good might come from this in the end.

P.S. if you are looking to connect with other patients, I’ve once heard from me-international.org that they have chat groups with a supposedly positive mood..

Have a good day!

Hi Cort, don’t forget all of Professor Newton’s research ( https://me-pedia.org/wiki/Julia_Newton) when you write the next blog.

It is not Vermoulen but Vermeulen 🙂

In fact, a breathing disorder can explain everything. I think hyperventilation has a medical reason, not a psychological one. If your oxygen intake is not going well, it works both ways. Then I come back to the brain stem.

I really should have looked up his name (lol) – I am probably never going to remember it right.

Righto regarding Dr. Newton. Haven’t heard much from her lately but she did an awful lot.

In my opinion, this is more than hyperventilating. I’ve spent years soinf buteyjo breath work which us essentially learning to reduce your breathing 24/7.

It helps but it’s no cure

I suspect that when medical researchers actually start studying fascia and it’s role in circulation and nerve conduction, we’ll start putting more puzzle pieces together.

I know it’s not psychological- I was always someone who woke up at 5:30 to do yoga and hiked a couple of miles after working all day. I also meditated daily for years before the injury that triggered my CFS. I’ve never had depression or anxiety, although I did get an ADHD diagnosis last year at age 52.

I do mixed workouts-a little bit of weights, a little bit of walking, a little bit of dancing, a little bit of isometrics. But if I overdo activity I crash and have the insomnia and tachycardia and all kinds of malaise. It’s a very fine line to walk, to exercise just enough to feel better and not worse.

Has anyone tried a PEMF mat? If so, did it help?

Very interesting. Research over years frequently comes back to the same problem with mitochondria. Analysis of complex pathways is useful. I wonder if there will ever be some deep research into the cause ? And if there is a causative

agent / s, then that might provide an approach to treatment ?

Re: Beatrice Ranque, “she fell back on the weak argument that because normal physical examinations and routine test results suggest that “no organic impairment” exists in long COVID, psychological factors must be important.” Weak is an understatement! I was very sick for 7 months after getting bitten by a deer tick and the VA Dr refused to treat me because the Lyme tests were negative. Never tested me for anything else because my bllod work was “normal” and my symptoms invisible. Turns out I had Anaplasmosis and not getting treatment led to CFS and then to MCAS. Per Dr Ranque’s “theory” my CFS and now MCAS are psychological? I’d like to suggest in agreement with Dave W’s post below, she look in the mirror for the psych issues.

Hi Cort,

Since 2010, I’ve been researching muscle weakness and have confirmed two diagnoses: ACTN3 gene deficiency (R577X variant) and post-polio syndrome. A third possibility, dysferlinopathy (DYSF-related disease), is currently scheduled for evaluation. https://www.mdc-berlin.de/news/press/developing-crispr-therapy-muscular-dystrophy

In the process, I’ve also discovered that there are many other potential factors, most of which appear to have epigenetic markers.

Hi Sieglinde, just to clarify, do you mean you have been doing general research on which diagnoses have a connection to muscle weakness; or do you experience muscle weakness yourself and have confirmed your own diagnoses?

I have an acquaintance with post-polio, who, remarkably, has the very same problems with hand/arm movements being particularly taxing in typical “cleaning” movements, that I do with ME/CFS.

Hi JR,

I have a clinical diagnosis from a specialist in the UK affecting my leg muscles, making it difficult for me to walk up hills or climb steps. I also have a DNA-confirmed ACTN3 gene deficiency. However, I believe my skeletal muscle weakness, particularly in my arms and shoulders, may be related to Dysferlinopathy (DYSF-related diseases), as I have the DYSF gene. Hopefully, this will be confirmed with a biopsy soon.

I struggle to lift my arms beyond shoulder height and find it difficult to do tasks that require bending forward. Driving long distances while holding the steering wheel is also challenging.

Thank you Sieglinde, good luck with the biopsy and best wishes!

I have no appointment yet, but there is additional information.

According to this: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NvV2xTrShvg&t=31s

in the (0.57 Minute), dysferlin mutation prevents effective sarcolemma repair, leading to calcium overload, chronic inflammation, and muscle fiber degeneration, which drive the progression of dysferlinopathy-related muscular dystrophies. Dysferlin mutation disrupts the sarcolemma’s repair mechanism, leading to chronic damage ion imbalance, inflammation, and progressive muscle degeneration.

Hehe, with severe ME/CFS, everything IS exercise. I am still puzzled why I have not more muscular loss, attribute it to the constant state of nervous system overarousal kind of keeping up a probably constantly enhanced muscle tonus, and or constantly operating at the muscular capacity limit even with small tasks.

I have a friend with mild post-Covid ME/CFS, who discovered there is actually a safe threshold below which he can safely do mild exercise.

But discussion of exercise benefits should never, ever forget that this works only in patients, who are functional enough that exercise time does not take away from needed resting time. In many, particular in patients wired to be active with high nervous system arousal, in my opinion much more benefits can be derived from truly learning how to rest, and when instead trying to exercise, the benefits if true rest will instead be lost.

Secondly. my friend who benefits from a clear exercise threshold, does not experience the phenomenon of exertion-limits masking nervous system hyperarousal the way I do, which can also make exercise dangerous because exercise itself can cause a pleasant hyperarousal that will then mask safe limits.

Thirdly, as I’ve said before, I think the perspective benefits of movement of the body should not be limited to just exercising and strenght building. In my opinion, keeping the fascial system fluid, circulation and so-to-say “the juices flowingq and the body mobile are health benefits of movement that have nothing to do with strength building, but may actually be more important for a chronic illness patient.

For me with severe ME/CFS, walking stretches/mobilisation in my flat in the morning, stretches against the wall in the evening if I can, and one full body muscle relaxation practice at rest is what I incorporate into the day if possible.

As for rest versus exercise, the timing may also matter: Not to forget that for some patients, there seems to possibly be a “window of opportunity” right at the start of postviral illness where resting can in the optimal case lead to full recovery. My best friend’s co-worker recovered fully from post-Covid by following Charité Berlin’s (the university clinic where Scheibenbogen researches) instructions for rest in the convalescence phase and breathing exercises provided by Charité, sticking with determination to her couch and fending off relatives’ initial insistence that she exercise. Today she does heavy physical work renovating her house.

Of course I do not advocate total immobility. However, in my opinion the following might sum it up:

In ME/CFS, exercise is body maintenance (and I suppose might have some antinflammatory infects). Rest however has a potential to be curative in particular close to early onset.

To me this makes sense as I imagine resting early on and avoiding all risk of overexertion may give the body system the opportunity to calm down, while on the other each event of overexertion that causes PEM will kind of “fire up” the disease process anew.

As for the “allostatic load” (= kind of damage from chronic stress?) argument, it goes to show that BPS views can be rather undifferentiated: According to a European survey https://www.europeanmealliance.org/documents/emeaeusurvey/EMEAMEsurveyreport2024.pdf , I think 12% of ME/CFS patients reported traumatic life event/stress as an initial trigger for onset of ME/CFS, while stress itself is an epigenetic mediator, an immune event and a known initial trigger for various autoimmune diseases. So, the fact that those patients report stress as a trigger still does not mean that ME/CFS itself is psychosomatic, just that in 12% of patients, an additional layer of possible stress damage effects could be expected too due to their history, and that this stress possibly (co-)functioned as the immune or epigenetic trigger that caused initial outbreak of ME/CFS.

It’s known now that there are at least two subtypes of long covid – POTS and PEM (although they can overlap). When are the studies going to start differentiating between those two groups to see if exercise is doing different things in each subtype?

The two should definitely be differentiated in the research. Then you have people like me who have both. Exercise might help my POTS symptoms but it wrecks me because of the PEM.

My time is running out, but I still hang onto the hope that a new finding might permit me some life energy, peace and joy before my days are up.

Beyond specific research breakthroughs (that could happen any day), I perceive an extra dimension of hope from the application of AI to medicine and biochemistry. AI has the capacity (that humans don’t) to consider the interactions of hundreds to thousands of biochemicals at the same time in a dynamic (rather than static) model. Imagine if we could apply AI to finally allow us to define “biochemical balance” (or homeostasis if you prefer) in a healthy or symptom free body. Once we understand what constitutes a biochemical balance within and between all systems (which = health), THEN we would be able to identify the presence of any biochemical imbalance(s) – which manifest as chronic symptoms or disease – including CFS, Fibro and Long Covid. Identifying the biochemical imbalances that underlie each disease – would actually (scientifically) define the disease. In fact, you could define CFS (or Fibro or Long Covid) as a chronically imbalanced homeostasis – that causes (our) chronic symptoms. If we can figure out how and why our biochemistry is chronically imbalanced, a cure or effective treatment may follow soon thereafter – if we can then address the cause(s).

In simpler terms, AI might be able to determine the significance of new research findings – while considering (and reconciling) the findings of all previous research. Can you imagine that? This is well beyond the capacity of the human brain. I don’t know if this is in the cards, but the application of AI to understand the complexities of biochemistry, health and disease does provide me with a measure of hope, as AI capabilities are being expanded and refined rapidly in this age.

I like how points for hope are collected in this blog.

Another reason for hope is the advancement of bioengineered treatment technology. I’m thinking of this 2022 article on a discovery of how viruses interact with cells by sending out microRNAs and concludes: “This also opens up new therapeutic possibilities: Artificial small RNAs can be designed to specifically switch off individual members of microRNA families.” https://www.uni-wuerzburg.de/en/news-and-events/news/detail/news/herpesviruses-awaken/ By the way, Prusty has since relocated to Riga university (Latvia), where he is in the process of building up research infrastructure and continues to work on “chronic viral illnesses, like chronic fatigue syndrome” https://www.rsu.lv/en/news/pioneering-virology-research-tenured-professor-bhupesh-prustys-impact-rsu

Ganz lieben Dank für diesen Blogbeitrag.

Ich versuche, die kleinen Studienergebnisse irgendwie für mich zu nutzen, auch wenn es noch keine offizielle Behandlung gibt.

Als ich zum Beispiel erfuhr, dass bei Menschen mit PEM die Muskelmembranen beschädigt sind und gleichzeitig die Hitzeschockproteine zu wenig, habe ich wieder angefangen, täglich meine Infrarotsauna zu nutzen. Denn bei einem 30-minütigen Nutzen einer solchen Sauna bei 37°C, sollen vermehrt Hitzeproteine gebildet werden. Wie weit es hilft, weiß ich nicht, aber es gibt mir das Gefühl, etwas zu tun, wenn ich schon kaum “trainieren” kann.

Wenn ich lese, dass oxidativer Stress ein Problem ist, konsumiere ich mehr Antioxidantien.

Uns so weiter. Diese kleinen Forschungsergebnisse verhindern, dass ich mich hilflos fühle, weil ich selber kleine Ansätze habe, die hoffentlich meinem Körper eine Hilfestellung bieten.

“Google Translation”

Thank you very much for this blog post. I try to use the small study results for myself somehow, even if there is no official treatment yet.

For example, when I learned that the muscle membranes of people with PEM are damaged and at the same time the heat shock proteins are too few, I started using my infrared sauna every day again. Because with a 30-minute use of such a sauna at 37°C, more heat proteins are supposed to be formed.

I don’t know how much it helps, but it gives me the feeling of doing something when I can hardly “train”. When I read that oxidative stress is a problem, I consume more antioxidants. Us so on. These small research results prevent me from feeling helpless, because I have small approaches myself that hopefully offer my body a help.

mediaction: salbutamol (a β2-agonist) , verapamil (Calcium channel blocker that may help reduce calcium overload and protect mitochondria) and enalapril (ACE inhibitor thsat reduced sodium retention, potentially alleviating some of the stress on muscle cells.) Supporting Mitochondrial: Coenzyme Q10, L-carnitine and Magnesium

Hi Javier, are you suggesting this. or taking this yourself and does it help you? Thank you!

both, i started yesterday and i wanted shared a medication reasoning based on Cort assumptions on “Electrophysiological alterations” at this blog

Thanks for explaining and good luck! Maybe you could add a reply here after some time how it’s going with these meds!

How much coq10 do you take?

I’ve been taking 400mg for yrs..My Dr told me and my mother we were low, so we started it back in the early 2000s..It helped with energy.

I take magnesium glycinate 200mg and it helps with muscle cramps and tingling.I haven’t tried l-carnitine..How does that work..I’ve had long covd since 2021..I’m 73 and I can’t stand how I feel..Body has been wiped out from it..Pain in joints..lots of inflammation..blood flow..nerves the whole basket of it all..So depressed. Thank you all for your research and input.

I really appreciate all of Cort’s efforts summarizing research and other developments in the area of ME/CFS and L-COVID.

That said, in this article I disagree with his characterization of the term “biopsychosocial” model. As a clinical/forensic psychologist who is fairly knowledgeable about the treatment of chronic pain, the “psychological” component of treatment is in no way meant to imply the pain is “all in your head”. Rather, in chronic pain there are typically bi-directional psychological processes: “While pain can influence a person’s mood, emotions, and mental health, those factors can also influence a person’s experience of pain. This exchange happens partly because the brain systems involved in emotions, mood, some mental health conditions, and pain overlap” (NIH). For example, research indicates that clinical depression, anxiety disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and sleep problems commonly co-occur with chronic pain.

Best,

Brian, Kingston, ON

Reply

Submit a Comment

You are correct and I did not mean to imply that every aspect of the biopsychosocial model is bad. I don’t believe that at all, and, in fact, I didn’t include one part of the blog which showed that some of the techniques used are virtually similar to those that Toni Bernhard uses in her “How to be Sick” book. (I felt the blog would have been too long). I think it was badly applied in ME/CFS in the UK and elsewhere, though, because it promised much more than it delivered and sidelined ME/CFS research there for over a decade.

If had been used as an adjunct to ME/CFS – as it was in fibromyalgia – I think everyone would have been better off. Looking a chronic pain research I was surprised at how helpful some of these techniques can be and we will have some blogs on that.

Yes, that is the approach of psycho-social approaches to chronic pain; these are typically used as adjunct treatments with modest expectations for improvement tailored to the individual. For example, I would rarely introduce mind-body interventions — such as “mindfulness” — as an intervention until a thorough understanding of the rationale for a psycho-social approach is explained (e.g., gate control -neuromatric model) , and the patient agrees with this rationale. Sometimes “motivational interviewing” is beneficial to clarify a patient’s motivation for change, such as what is used on addictions treatments. Thereafter, psychotherapy begins usually starting with the “stress-judging-pain connection”. Overall the approach is called Cognitive Behaviour Therapy (CBT), but that term is a bit misleading; at no time is chronic pain regarded as primarily psychological: i.e., “all in the patient’s head”. To me one of the best workbooks in the area is “Cognitive Therapy for Chronic Pain: A Step-By-Step Guide” by Dr. Beverly Thorn (2017, 2nd ed).

While advances continue in psycho-social approaches to chronic pain, such as as the promising “pain reprocessing therapy” or approaches that treat past trauma (which is pretty common in individuals who experience chronic pain), unfortunately, some of the marketing claims raise red flags in terms of claims to “cure” or “heal” chronic pain — and indirectly implying that chronic pain only due to “brain pain circuits misfiring”. For example, the book, “The Way Out: A Revolutionary, Scientifically Proven Approach to Healing Chronic Pain

Pain Reprocessing Therapy (PRT) (2022)”. Of course, in the latter approach (or any treatment proclaiming unreasonable expectations), if the patient’s pain is not “healed” the patient might be blamed.

Returning to ME/CFS, there is something to learn from the psycho-social approach to treating chronic pain, but there is also a distinct history; of MD/psychiatrists/researchers further victimizing ME/CFS patients real suffering and disability as “psychological/psychiatric”. I think that is what Cort was concerned about in this column.

Again, great website Cort!. Thanks so much for your continued work.

Dr Wust seems to be doing a great job investigating this topic. I too was wondering whether low blood volume could be contributing to any of the abnormalities he found. Maybe he will see your article, Cort, and add that to his next study!

I can not believe after all the pain and suffering all the people with ME/CFS, FM and long Covid are going through for years or decades that we are still hearing such offending and stupid comments like that:

”For instance, Beatrice Ranque, the lead author of the reply, concluded that because normal physical examinations and routine test results suggest that “no organic impairment” exists in long COVID, psychological factors must be important.”

With researchers like that, we are not out of the woods. Fortunately, they are not all the same, far from that.

Mecfs is a spectrum disease someone with severe me could not tolerate walking even or lifting weights. I was severe for years then moderate to light now mostly bed bound again. As for FM I had that 12 years before I became bedridden after the flu with mecfs. Yes I could function with FM and take walks go on vacations etc But I had alot of pain once I got frozen shoulder but then times my FM was not even noticeable no PEM ever. But some simularites with mecfs like sensitivity to light fatigue but more mild. I wonder if long covid is mecfs it sounds so much like it is.

How I wish that the biopsych crowd would stop undermining good research and cluttering up the field with their defunct theories. They’re not doing PwME/LC any good by getting in the way and refusing to learn.

I wish they would stop studying symptoms in isolation. PEM is just one outcome of ME/CFS and Long Covid. From LC, you can also have a stroke or heart attack after even a mild case of Covid. To my sorrow, I also learned that the single symptom of LC may be hearing loss. As far as ME/CFS, I have had several episodes of serious infections that took months to heal.

I would like to see ophthalmologists, immunologists, ENTs, cardiologists, urologists, etc. in one place studying all of the horrible outcomes of these illnesses in a group of patients.

From my experience, these two illnesses can affect every part of your body and these endless studies of PEM are not getting any closer to causes or treatments.

But, this will never happen because researchers are each concerned with supporting their own department or lab and collaboration (while beneficial for the patient) is not how the “more study is needed industry” works.

It seems to me that Rob Wust is researching ME/CFS under a Long Covid label. It looks as if he has made PEM a required criteria for who entered his exercise study group. And thus he might actually have worked with an ME/CFS group.

I think this highly problematic and dangerous. Because Long Covid has so many faces and only a small group of them actually have ME. However, it seems that except for this main flaw the rest of Wust’s research is of a high standard.

Hi Lina, I wasn’t suggesting that Dr. Wust’s research was not of high standard.

Both ME/CFS and Long Covid (I have both) are far too complex to continue to focus on PEM.

ME/CFS is unlikely to kill you, but Long Covid can. Heart attacks and strokes are increased in the year after even a mild case of LC.

I don’t think these are the same illnesses and trying to lump them together does not produce reliable research for either group.

How does Wust’s muscle study relate to the work done by Scheibenbogen and Wirth recently? It sounds somewhat similar.

My guess is that it is quite similar. They have a recent paper out that extends their hypothesis. They feel like things are lining and they’re getting closer and closer. A talk with Klaus Wirth is coming up.

Hi Cort, sorry for the late response. When you say closer and closer, to what exactly do you mean? A treatment? Answers? A more validated disease model?

Cort, you need meaningful feedback,

and I would say that your finding this study,

for one thing

and covering it,

for another

is Major ! This is obviously not your first cfs rodeo. ( 😉 )

That compliment is equally important with the next distinction.

2ndly,

I needed, right away to disagree with an early comment by you in the blog:

“”The most obvious explanation – low levels of blood vessels feeding the muscles – didn’t pan out, as the ME/CFS patients had plenty of blood vessels (capillaries) feeding their muscles.””

Please remember, Cort and readers, that my ONLY goal is HEALING…RECOVERY for each and all of you readers and contributors, and my peculiar gift is logic and analysis.

Regular blood vessels and capillaries are NOT the same. (and neither type is the same as an artery)

Capillaries are